THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL of ATHENS

Part 4 – the Sophists

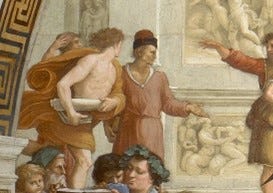

Now, we must leave the first scene, of the Pre-Socratic Philosophers, and shift our attention to those persons who are standing above them, on the second level at the top of the stairs. First, let’s look at those people on the left side of this scene, above the pre-Socratic philosophers. And at the far left edge of the painting is a group of three people.

The first person that we see is mostly hidden, except for his head, and holding his hand to his hat at the side of his head, he seems to be trying to look ahead at someone, as if looking at the unfolding of this scene. It’s as if he’s the announcer for this scene.

In front of this person – the announcer of this scene, is someone who is running past him, whose cloak is revolving around in circles, holding in his hands a book and also a letter that is rolled up like his cloak, and who is also looking ahead at a group of people.

Because this person is holding a book and is holding a scroll, I thought that it could be Xenophon, who wrote many books, and who also wrote about conversations as they occurred.

The writings of Xenophon that have survived are his histories - ‘Anabasis’, ‘Hellenica’, and ‘Agesilaus’, his treatises – ‘The Cavalry General’, ‘On Horsemanship’, ‘The Sportsman’, ‘On Revenues’, and ‘The Laws of Sparta and Athens’, and his dialogues – ‘Hiero’, and ‘The Economist’, and especially his dialogues concerning Socrates – ‘Memorabilia of Socrates’, ‘Apology of Socrates’, and ‘Symposium’.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Xenophon, the son of Gryllus, a citizen of Athens, was of the borough of Erchia; and was a man of great modesty, and as handsome as can be imagined.

II. They say that Socrates met him in a narrow lane, and put his stick across it, and prevented him from passing by, asking him where all kinds of necessary things were sold. And when he had answered him, he asked him again where men were made good and virtuous. And as he did not know, he said, ‘Follow me, then, and learn’. And from this time forth, Xenophon became a follower of Socrates.

III. And he was the first person who took down conversations as they occurred, and published them among men, calling them memorabilia. He was also the first man who wrote a history of philosophers.

V. He became a friend of Cyrus in this manner. He had an acquaintance by the name of Proxenus, a Boeotian by birth, a pupil of Gorgias of Leontini, and a friend of Cyrus. He, being in Sardis, staying at the court of Cyrus, wrote a letter to Athens to Xenophon, inviting him to come and be a friend of Cyrus. And Xenophon showed the letter to Socrates and asked his advice. And Socrates bade him go to Delphi and ask counsel of the god. And Xenophon did so, and went to the God; but the question he put was, not whether it was good for him to go to Cyrus or not, but how he should go; for which Socrates blamed him, but still advised him to go. Accordingly, he went to Cyrus, and became no less dear to him than Proxenus. And all the circumstances of the expedition and the retreat, he himself has sufficiently related to us.

VI. But after the expedition, and the disasters which took place in Pontus, and the violations of the truce by Seuthes, the king of the Odrysae, he came into Asia to Agesilaus, the king of Lacedaemon, bringing with him the soldiers of Cyrus, to serve for pay; and he became a very great friend of Agesilaus. And about the same time, he was condemned to banishment by the Athenians, on the charge of being a favourer of the Lacedaemonians.”

So, I think that this person should be Xenophon, who is carrying his book and his paper for writing, and who perhaps is rushing to tell Socrates the answer that he had received from the oracle, but who also may be rushing to get past the person in front of him, that Xenophon may be looking.

And, if we now look in front of Xenophon, we see a person standing, who is also wearing a hat, but who is holding out his arm with his hand opened, as if ready to receive something. This person, I think, could be Protagoras, who was one of the sophists that asked payment from their students.

The fragments of Protagoras can be found in ‘Ancilla To the Pre-Socratic Philosophers’, translated by Kathleen Freeman (Harvard University Press) from the Vorsokratiker Fragmente by Hermann Diels.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Protagoras was the son of Artemon ... He was a native of Abdera ...

III. He was the first person who asserted that in every question there were two sides to the argument exactly opposite to one another. And he used to employ them in his arguments, being the first person who did so. But he began something in this manner: ‘Man is the measure of all things: of those things which exist as he is; and of those things which do not exist as he is not.’ And he used to say that nothing else was soul except the senses, as Plato says, in the Theaetetus: and that everything was true. And another of his treatises he begins in this way: ‘Concerning the Gods, I am not able to know to a certainty whether they exist or whether they do not. For there are many things which prevent one from knowing, especially the obscurity of the subject, and the shortness of the life of man.’

And on account of this beginning of his treatise, he was banished by the Athenians. And they burnt his books in the market-place, calling them in by the public crier, and compelling all who possessed them to surrender them.

He was the first person who demanded payment of his pupils; fixing his charge at a hundred minae. He was also the first person who gave a precise definition of the parts of time; and who explained the value of opportunity, and who instituted contests of argument, and who armed the disputants with the weapon of sophism. He it was who first left facts out of consideration, and fastened his arguments on words; and who was the parent of the present superficial and futile kinds of discussion.”

And I think that this person should be Protagoras - ‘the first person who demanded payment of his pupils’ and who seems to be holding out his hand for payment. And perhaps the person to the right of Pythagoras, is holding out his hand as if dropping something into Pythagoras’s hand.

But these two persons seem to be separated from the rest of the people in this scene, because in front of them is a person who perhaps is looking at them and may ne dropping something into Protagoras’s hand. But perhaps, he may be pointing them away. And so, I think that these two persons should be Xenophon and Protagoras, because both were banished from Athens – but at different times and for different reasons.

But more should be said about these sophists.

The following is from ‘The Life and Character of Socrates’ by Moses Mendelssohn.

“… At that time, in Greece, as at all times with the rabble, the kind of scholars who enjoyed great esteem, encouraged established prejudice and obsolete superstitions, through all kinds of pretexts and sophisms. They gave themselves the noble name of Sophists, which, due to their behavior, became a repulsive name. They took care of the education of the youth, taught the arts, sciences, moral philosophy and religion, in both public schools and private houses, with general acclaim. They knew that, in democratic government assemblies, eloquence was treasured above all, that a licentious man would gladly listen to mere chatter about politics, and, that shallow minds would rather fulfil their desire for knowledge with fairy tales. Hence, they never neglected glittering eloquence in their presentations, and so skillfully wove together false politics and absurd fables, that the people listened with astonishment, and lavished them with rewards.

They were on good terms with the priests; for they mutually adopted the wise maxim: live and let live. If the tyranny of hypocrites was no longer able to hold the free spirit of humanity under the yoke, so these false friends of truth were employed, to lead it astray on the false path, to jumble together natural conceptions, and suspend all distinction between truth and falsehood, right and wrong, good and evil, through blinding fallacies. The principal axiom in their theory was: Everything can be proved, and everything can be disproved; and in the process, one must profit as much from the folly of others, and from his own superiority, as he can. This last maxim, they, of course, kept secret from the public, as one can easily imagine, and entrusting it only to their inner circle, who participated in their business. However, the ethic they taught publicly, was just as corrupting for the heart of men, as their politics were for the justice, freedom, and happiness of the human race.

Since they were crafty enough to weave together their own interests with the prevailing religion, not only were decisiveness and heroism necessary to put an end to their frauds, but, even a true friend of virtue might not dare to attempt it without the utmost precaution and foresight. There is no religious system so corrupt, that it does not pay homage to some of man's responsibilities, which the humanist honors, and the reformer of morals, if he doesn't want to act contrary to his own purpose, must leave intact. From doubt in religious affairs, to frivolousness; from neglect of religious rites, to the contempt of worship generally; the transition tends to be very easy, especially for minds which are alienated from the rule of reason, and are ruled by avarice, ambitiousness, or lust. The priests of superstition depend, all too often, on this deception, and took refuge in it, as an inviolable shrine, whenever there was an attack on them.

Such difficulties and obstacles stood in Socrates’ way as he made the great decision, to spread virtue and wisdom among his fellow men ...”

With the sophists now seen for what they truly were, perhaps we can make our way to Socrates, to see more of the virtue and wisdom that he was trying to spread, in his battles against these sophists.

[ next week - part 5 - the followers of Socrates ]