THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL of ATHENS

Part 5 – the Followers of Socrates

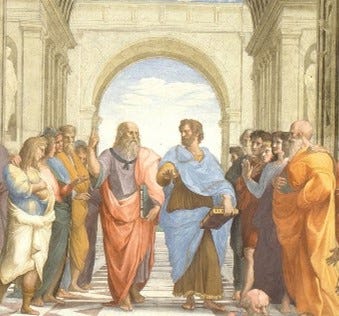

Next, looking in front of Xenophon and Protagoras, and towards whom Xenophon seems to be rushing, is a group of six persons – and the person farthest to the right and facing him, is someone counting on his fingers and looking at the other five people as if trying to teach them. This person, standing directly above, as if on the shoulders of Thales, could be the teacher of Xenophon, Socrates.

No writings by Socrates exist, but only discourses of Socrates written by Xenophon and Plato.

The following is from ‘The Life and Character of Socrates’ by Moses Mendelssohn.

“Socrates, son of Sophroniscus and the midwife Phaenarete, was the wisest and most virtuous among the Greeks. He was born in the fourth year of the 77th Olympiad, in Athens, into the Alopecian clan. In his youth, his father encouraged him in the art of sculpture, in which Socrates must have made no little progress, if those who assert are correct, that the robed Graces, which stood behind the statue of Athena, on the wall at Athens, are his work. In the time of Phidias, Zeuxis, and Myron, no mediocre work could have been granted such an important place ...

Socrates enjoyed instruction from, and conversation with, the most famous people in all the arts and sciences, among whom his disciples named Archelaus, Anaxagoras, Prodicus, Evenus, Isymachus, Theodorus, and others.

Crito furnished him with the necessities of life, and Socrates, from the beginning, diligently pursued natural philosophy, which was very much in vogue at that time. He soon decided however, that it were time that wisdom be transferred from the investigation of nature to the contemplation of humanity.

This is the path which philosophy was to take for all time …”

And, to the left of Socrates, is someone who is looking intently and admiringly at Socrates, while leaning his head on one hand, while leaning on the column. And this could be one of Socrates’s most devoted followers, and that could be Aeschines.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius, in ‘Life of Aeschines’:

“I. Aeschines was the son of Charinus, the sausage-maker … he was a citizen of Athens, of an industrious disposition from his boyhood upwards, on which account he never quitted Socrates.

II. And this induced Socrates to say, the only one who knows how to pay us proper respect is the son of the sausage-maker.

III. … The Dialogues then of Aeschines, which profess to give an idea of the system of Socrates are, as I have said, seven in number. First of all, the Miltiades, which is rather weak; the Callias, the Axiochus, the Aspasia, the Alcibiades, the Jelanges, and the Rhino.”

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius, in ‘Life of Socrates’:

“XVI. … When Aeschines said, ‘I am a poor man, and have nothing else, but I give myself’; ‘Do you not,’ Socrates replied, ‘perceive that you are giving me what is of the greatest value’?”

And, to the left of Aeschines, is an older, shorter man, wearing a hat, who is also looking intently at Socrates. This could be Crito – ‘who furnished him [Socrates] with the necessities of life’.

The following is from ‘The Life and Character of Socrates’, by Moses Mendelssohn:

“When Socrates was about 30, and his father was long dead, he was still pursuing the art of sculpture, but from necessity, and without much inclination. Crito, an aristocratic Athenean, became acquainted with him, observed his sublime talents, and judged that he could be far more useful to the human race through his intellect, than through his handiwork. Crito took him out of art school, and brought him to the intellectuals of the time, in order to allow beauties of a higher order to be put before him for contemplation and emulation. In the same way that art teaches the means by which the lifeless can imitate life, stone can be made to resemble the human form; wisdom seeks, on the other hand, to imitate the infinite in the finite, so as to bring the soul of humanity, as close as is possible, in this life, to its original beauty and perfection.”

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius, in ‘Life of Crito’:

“I. Crito was an Athenian. He looked upon Socrates with the greatest affection; and paid such great attention to him, that he took care that he should never be in want of anything.

II. Crito wrote seventeen dialogues, which were all published in one volume; and I subjoin their titles: That men are not made good by teaching; on Superfluity; what is Suitable, or the Statesman; on the Honourable; on doing ill; on Good Government; on Law; on the Divine Being; on Arts; on Society; Protagoras, or the Statesman; on Letters; on Political Science; on Learning; on Knowledge; on Science; on what Knowledge is.”

And, standing behind, and looking over the shoulder of Crito at Socrates, is someone with slightly ruffled-looking hair and beard. This could be Phaedo.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius, in ‘Life of Phaedo’:

“I. Phaedo the Elean, one of the Eupatridae, was taken prisoner at the time of the subjugation of his country, and was compelled to submit to the vilest treatment. But while he was standing in the street, shutting the door, he was met with Socrates, who desired Alcibiades, or as some say, Crito, to ransom him. And after that time, he studied philosophy as became a free man.

II. And he wrote dialogues, of which we have genuine copies; by name - Zopyrus, Simon, and Nicias (but the genuineness of this one is disputed); Medius, which some people attribute to Aeschines, and others to Polyaenus; Antimachus, or the Elders (this too is a disputed one); the Scythian discourses, and these, too, some attribute to Aeschines.”

And, standing to the left of Crito and listening to Socrates, is a young man in a colorful military uniform, wearing a helmet, with his right hand resting on his sword. This could be Alcibiades.

And, standing behind Alcibiades, and also dressed in military attire, is a man who has his head turned away from Socrates, and is holding his hand as if dropping something into the hand of Protagoras, the sophist. This could be Critias.

The following is from ‘The Life and Character of Socrates’ by Moses Mendelssohn.

“No one was as close to him [Socrates] as Alcibiades, a younger man of uncommon good looks and great talent, who was arrogant, brave, thoughtless, and above all, of fiery temperament. He pursued Alcibiades tirelessly, engaged him in discussion at every opportunity, to prevent him, through friendly admonition and loving rebukes, from the excesses of ambition and lasciviousness, to which he tended by nature ...”

“The following year, the Athenians were decisively defeated by the Lacedemonians, their fleet levelled, their capital besieged, and brought to such an extreme, that they had to surrender, unconditionally. It is very likely, that the lack of experienced commanders on the Athenian side, was, at least in part, the cause of this defeat. Lysander, the commander of the Lacedemonians, who had taken the city, promoted a rebellious faction, transformed the democratic government into an oligarchy, and installed a Council of Thirty, who were known by the name of the Thirty Tyrants. The cruelest enemy would not have been able to rage in the city, as these monsters raged ...

How Socrates’ heart must have bled to see Critias, who had formerly been a student, in the leadership of this holy terror! Yes, Critias, his former friend and pupil, now proved himself to be an open enemy, and sought the opportunity to persecute him. The wise man had once harshly rebuked him for his swinish and perverted lechery, and since that time, the ogre bore a secret resentment, which increasingly sought an opportunity to erupt. When he and Charicles were named as legislators, they introduced a law that no one should teach rhetoric, in order to find a reason to indict Socrates.”

The story of what happened to Alcibiades and Critias can be seen in the following from the ‘Memorabilia of Socrates’, by Xenophon:

“ ‘But,’ adds his accuser, ‘Critias and Alcibiades were two of his intimate friends; and these were not only the most profligate of mankind, but involved their country in the greatest misfortunes; for, as among the thirty – none was ever found so cruel and rapacious as Critias; so, during the democracy, none was so audacious, so dissolute, or so insolent, as Alcibiades.’

Now I shall not take upon me to exculpate either of these men; but shall only relate at what time, and, as I think, to what end, they became the followers of Socrates.

Critias and Alcibiades were, of all the Athenians, by nature the most ambitious; aiming, at what price soever, to set themselves at the head of the commonwealth, and thereby exalt their names beyond that of any other: they saw that Socrates lived well satisfied with his own scanty possessions; that he could restrain every passion within its proper bounds, and lead the minds of his hearers, by the power of his reasoning, to what purpose he most desired. Understanding this, and being such men as we have already described them, will anyone say it was the temperance of Socrates, or his way of life, they were in love with; and not rather, that by hearing his discourses, and observing his actions, they might the better know how to manage their affairs, and harangue the people?

And, truly, I am thoroughly persuaded, that if the gods had given to these men the choice of passing their whole lives after the manner of Socrates, or dying the next moment, the last would have been preferred, as by much the most eligible. And their own behaviour bears sufficient testimony to the truth of this assertion; for, no sooner did they imagine they surpassed in knowledge the rest of their contemporaries, who, together with themselves, had attended on Socrates, but they left him, to plunge into business and the affairs of the administration; the only end they could propose in desiring to associate with him ...

… wherefore I can well imagine that even Alcibiades and Critias could restrain their vicious inclinations while they accompanied with Socrates and had the assistance of his example: but being at a distance from him, Critias retiring into Thessaly, there very soon completed his ruin, by choosing to associate with libertines rather than with such as were men of sobriety and integrity; while Alcibiades, seeing himself sought after by women of the highest rank, on account of his beauty; and at the same time much flattered by many who were then in power, because of the credit he had gained, not only in Athens, but with such as were in alliance with her: in a word perceiving how much he was the favourite of the people, and placed, as it were, above the reach of a competitor, neglected that care of himself which alone could secure him; like the athletic, who will not be at the trouble to continue his exercises, on seeing no one near able to dispute the prize with him. Therefore, in such an extraordinary concurrence of circumstances as befell these men, puffed up with the nobility of their birth, elated with their riches, and inflamed with their power, if we consider the company they fell into, together with their many unhappy opportunities for riot and intemperance, can it seem wonderful, separated as they were from Socrates, and this for so long a time too, if at length they became altogether degenerate, and rose to that height of pride and insolence to which we have been witnesses?

But the crimes of these men are, it seems, in the opinion of his accuser, to be charged upon Socrates; yet allows he no praise for keeping them within the bounds of their duty in that part of life which is generally found the most intemperate and untractable; nevertheless, on all other occasions, men judge not in this manner ...

… On the contrary, when Critias was insnared with the love of Euthydemus, he earnestly endeavoured to cure him of so base a passion: showing how illiberal, how indecent, how unbecoming the man of honour, to fawn, and cringe, and meanly act the beggar; before him, too, whom of all others he the most earnestly strove to gain the esteem of, and, after all, for a favour which carried along with it the greatest infamy. And when he succeeded not in his private remonstrances, Critias still persisting in his unwarrantable designs, Socrates, it is said, reproached him in the presence of many, and even before the beloved Euthydemus; resembling him to a swine, the most filthy and disgusting of all animals. For this cause, Critias hated him ever after; and when one of the thirty, being advanced, together with Charicles, to preside in the city, he forgot not the affront; but, in order to revenge it, made a law, wherein it was forbidden that any should teach philosophy in Athens: by which he meant, having nothing in particular against Socrates, to involve him in the reproach cast by this step on all the philosophers, and thereby render him, in common with the rest, odious to the people …”

I think this scene shows the battle between Socrates and the sophists, and between those of his followers who stayed true to his teachings – like Aeschines, Crito, Phaedo, and Xenophon, and those of his followers who were ensnared by Protagoras and the sophists – like Alcibiades and Critias.

Now, I think we are ready to arrive at the two persons in the centre of the painting – Plato and Aristotle.

[ next week - Part 6 - Plato and Aristotle ]