THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL of ATHENS

Part 6 – Plato and Aristotle

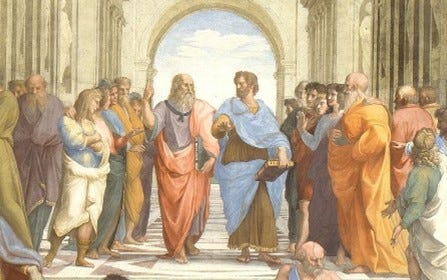

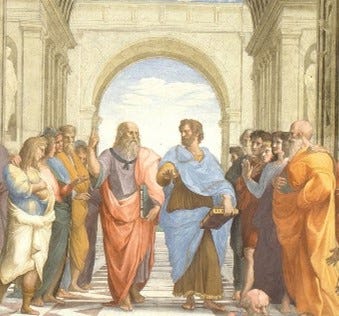

Next, looking to the right of Socrates and his students, in the centre of the painting, are two persons looking at each other, as if this is the central dialogue of the painting.

The person on the left seems to be walking towards us, and with one hand is carrying a book, titled ‘Timaeus’, and with the other hand is pointing up to the clouds in the sky, or, to the concentric arches, or, to that half of the painting occupied by the statues – the area of the gods. This must be Plato, who wrote a dialogue titled ‘Timaeus’.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Plato was the son of Ariston and Perictione, and a citizen of Athens; and his mother traced her family back to Solon; for Solon had a brother named Diopidas, who had a son named Critias, who was the father of Calloeschrus, who was the father of that Critias who was one of the thirty tyrants, and also of Glaucon, who was the father of Charmides and Perictione. And she became the mother of Plato by her husband Ariston, Plato being the sixth in descent from Solon.

IV. And he had brothers, whose names were Adimantus and Glaucon, and a sister named Petone, who was the mother of Speusippus.

V. … And he learnt gymnastic exercises under the wrestler Ariston of Argos. And it was by him that he had the name of Plato given to him instead of his original name, on account of his robust figure, as he had previously been called Aristocles, after the name of his grandfather.

VI. It is also said that he applied himself to the study of painting, and that he wrote poems, dithyrambics at first, and afterwards lyric poems and tragedies.

VII … and subsequently, though he was about to contend for the prize in tragedy in the theatre of Bacchus, after he had heard the discourse of Socrates, he learnt his poems, saying: ‘Vulcan, come here; for Plato wants your aid.’ And from henceforth, as they say, being now twenty years old, he became a pupil of Socrates … Afterwards, when he was eight and twenty years of age, as Hermodorus tells us, he withdrew to Megara to Euclides, with certain others of the pupils of Socrates; and subsequently, he went to Cyrene to Theodorus the mathematician; and from thence he proceeded to Italy to the Pythagoreans, Philolaus and Eurytus, and from thence he went to Egypt to the priests there; and having fallen sick at that place, he was cured by the priests by the application of sea water, in reference to which he said: ‘The sea doth wash away all human evils.’ And he said too, that according to Homer, all the Egyptians were physicians.

IX. And when he returned to Athens, he settled in the Academy, and that is a suburban place of exercise planted like a grove, so named from an ancient hero named Hecademus.

X. And Aristoxenus says that he was three times engaged in military expeditions; once against Tanagra; the second against Corinth, and the third time at Delium; and that in the battle of Delium he obtained the prize of pre-eminent valour.

XIV. And Plato made three voyages to Sicily, first of all, the purpose of seeing the island and the craters of volcanoes, when Dionysius, the son of Hermocrates, being the tyrant of Sicily, pressed him earnestly to come and see him ...

XV. But he went a second time to Sicily to the younger Dionysius, and asked him for some land and for some men whom he might make live according to his own theory of a constitution. And Dionysius promised to give him some, but never did it. And some say that he was in danger himself, having been suspected of exciting Dion and Thetas to attempt the deliverance of the island; but that Archytas, the Pythagorean, wrote a letter to Dionysius, and begged Plato off and sent him back safe to Athens.

XVI. The third time that he went to Sicily was for the purpose of reconciling Dion to Dionysius. And as he could not succeed, he returned to his own country, having lost his labour.

XXVII. He used also to wish to leave a memorial of himself behind, either in the hearts of his friends, or in his books.”

The following is from ‘The City of God’, Book 8, by St. Augustine:

“4. But, among the disciples of Socrates, Plato was the one who shone with a glory which far excelled that of the others, and who not unjustly eclipsed them all. By birth an Athenian of honourable parentage, he far surpassed his fellow-disciples in natural endowments, of which he was possessed in a wonderful degree. Yet, deeming himself and the Socratic discipline far from sufficient for bringing philosophy to perfection, he travelled as extensively as he was able, going to every place famed for the cultivation of any science of which he could make himself master. Thus he learned from the Egyptians whatever they held and taught as important; and from Egypt, passing into those parts of Italy which were filled with the fame of the Pythagoreans, he mastered, with the greatest facility, and under the most eminent teachers, all the Italic philosophy which was then in vogue. And, as he had a peculiar love for his master Socrates, he made him the speaker in all his dialogues, putting into his mouth whatever he had learned, either from others, or from the efforts of his own powerful intellect, tempering even his moral disputations with the grace and politeness of the Socratic style. And, as the study of wisdom consists in action and contemplation, so that one part of it may be called active, and the other contemplative, – the active part having reference to the conduct of life, that is, to the regulation of morals, and the contemplative part to the investigation into the causes of nature and into pure truth – Socrates is said to have excelled in the active part of that study, while Pythagoras gave more attention to its contemplative part, on which he brought to bear all the force of his great intellect.

To Plato is given the praise of having perfected philosophy by combining both parts into one. He then divides it into three parts – the first moral, which is chiefly occupied with action; the second natural, of which the object is contemplation; and the third rational, which discriminates between the true and the false. And though this last is necessary both to action and contemplation, it is contemplation, nevertheless, which lays peculiar claim to the office of investigating the nature of truth. Thus, this tripartite division is not contrary to that which made the study of wisdom to consist in action and contemplation.

... For those who are praised as having most closely followed Plato, who is justly preferred to all the other philosophers of the Gentiles, and who are said to have manifested the greatest acuteness in understanding him, do perhaps entertain such an idea of God as to admit that in Him are to be found the cause of existence, the ultimate reason for the understanding, and the end in reference to which the whole life is to be regulated. Of these three things, the first is understood to pertain to the natural, the second to the rational, and the third to the moral part of philosophy.

5. If, then, Plato defined the wise man as one who imitates, knows, loves this God, and who is rendered blessed through fellowship with Him in His own blessedness, why discuss with the other philosophers? It is evident that none come nearer to us than the Platonists.”

This seems to be saying that the philosophy of Plato comes closest to the philosophy of Augustine.

Next, to the right of Plato, and looking at him as if in discourse, is a younger man who is holding his hand out flat, as if in opposition to Plato pointing up, and who with the other hand is holding a book, titled ‘Ethics’, but who is resting the book on his leg in such a way to show that he is no longer walking with Plato. This must be Aristotle, who wrote a book titled ‘Ethics’.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Aristotle was the son of Nicomachus and Phaestias, a citizen of Stagira; and Nichomachus lived with Amyntas, the king of the Macedonians, as both a physician and a friend.

II. He was the most eminent of all the pupils of Plato; he had a lisping voice, as is asserted by Timotheus the Athenian, in his works on Lives. He had also very thin legs, they say, and small eyes; but he used to indulge in very conspicuous dress, and rings, and used to dress his hair carefully.

III. He had also a son named Nicomachus, by Herpyllis his concubine, as we are told by Timotheus.

IV. He seceded from Plato while he was still alive; so that they tell a story that he said, ‘Aristotle has kicked us off just as chickens do their mother after they have been hatched.”’

V. After that he went to Hermias the Eunuch, the tyrant of Atarneus, who, as it is said, allowed him all kinds of liberties ... Hermias had been a slave of Eubulus, and a Bithynian by descent, and that he slew his master ... Aristotle was enamored of the concubine of Hermias, and that, as Hermias gave his consent, he married her; and was so overjoyed that he sacrificed to her, as the Athenians do to the Eleusinian Ceres. And he wrote a hymn to Hermias.

VI. After that he lived in Macedonia, at the court of Philip, and was entrusted by him with his son Alexander as a pupil ... And when he thought that he had spent enough time with Alexander, he departed for Athens, having recommended to him his relation Callisthenes, a native of Olynthus; but as he spoke too freely to the king, and would not take Aristotle's advice he reproached him and said: – ‘Alas! my child, in life’s primeval bloom, Such hasty words will bring thee to thy doom.’ And his prophecy was fulfilled, for as he was believed by Hermolaus to have been privy to the plot against Alexander, he was shut up in an iron cage, covered with lice, and untended; and at last he was given to a lion, and so died.

VII. Aristotle then having come to Athens, and having presided over his school there for thirteen years, retired secretly to Chalcis, as Eurymedon, the hierophant had impeached him on an indictment for impiety … on the ground of having written the hymn to the beforementioned Hermias … And after that he died of taking a draught of aconite.”

The following is from ‘The City of God’, by St. Augustine:

“This has given them such superiority to all others in the judgement of posterity, that, though Aristotle, the disciple of Plato, a man of eminent abilities, inferior in eloquence to Plato, yet far superior to many in that respect, had founded the Peripatetic sect – so called because they were in the habit of walking about during their disputations – and though he had, through the greatness of his fame, gathered very many disciples into his school, even during the life of his master.”

In ‘The City of God’, Books 6 to 10, Augustine discusses heathen theology, and especially over the three books - 8, 9, and 10, he discusses natural theology and Platonism, where he said that ‘none come nearer to us than the Platonists’. But in all those books, Augustine mentions Aristotle in only this one single sentence, as if to show the unimportance of Aristotle’s ‘Ethics’, when compared to Plato’s ‘Timaeus’.

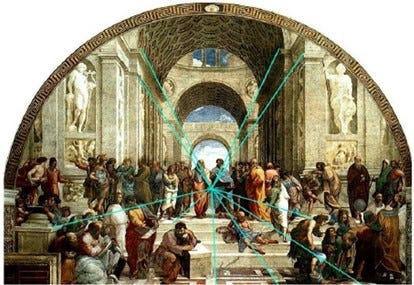

Looking again at these two persons closely, we can see that Aristotle is holding his hand out flat towards the floor – the earth. When we look at the floor, we can see that it has a square pattern, and if we take a straight edge and line it up with a side of a square that is running from front to back, and do this with all the different sides of the different squares, they all intersect at one point – at the ‘Timaeus’.

Then, we can see that Plato is pointing up, like the columns and pillars, towards the sky. When we look at a pillar, and again take a straight edge, and line it up with an edge of a block at the top of a pillar that is running from front to back, and do this with all the different pillars, they again all intersect – at the ‘Timaeus’.

In terms of perspective, we can see that the ‘Timaeus’ of Plato is the vanishing point of the painting – for both the bottom half of the painting (the earth) and the top half of the painting (the sky); for both the bottom half of the people in the painting – the earthly world of mankind, and the upper half of the two statues – the divine world of the gods.

Perhaps we need to look at how we came to have these two books, the ‘Ethics’ and the ‘Timaeus’.

After piecing together some scholiast fragments, a story was found that a Greek Egyptian named Thrasyllus became friends with a Roman named Tiberius while he was exiled at Rhodes. When Tiberius became Emperor, after the death of Augustus, Thrasyllus accompanied him back to Rome, where he became the Court Astrologer. Later, Thrasyllus assembled and arranged all of the dialogues of Plato (both the dialogues written by Plato and some spurious dialogues written by others), in the early years of the 1st century AD – 350 years after Plato’s death. [Thrasyllus died in 36 AD]

The ‘Timaeus’ had been partially translated into Latin (only the first half of the dialogue) in the 5th century AD, by Calcidius, and for about the next 1,000 years, it was the only dialogue that was available to people living in the latin west of Europe, until a great translation project, headed by Marsilio Ficino and financed by Cosimo de Medici, was started, and by 1484, Plato’s dialogues were published (in Latin) – over 1,800 years after he wrote them.

Thus, the importance of the ‘Timaeus’ in keeping Plato’s ideas alive. Now let’s look at the history of Aristotle’s ‘Ethics’.

The following is from the ‘Geography’, by Strabo:

“From Scepsis came the Socratic philosophers Erastus and Coriscus and Neleus the son of Coriscus, this last a man who not only was a pupil of Aristotle and Theophrastus, but also inherited the library of Theophrastus, which included that of Aristotle. At any rate, Aristotle bequeathed his own library to Theophrastus, to whom he also left his school; and he is the first man, so far as I know, to have collected books and to have taught the kings in Egypt how to arrange a library.

Theophrastus bequeathed it to Neleus; and Neleus took it to Scepsis and bequeathed it to his heirs, ordinary people, who kept the books locked up and not even carefully stored. But when they heard how zealously the Attalic kings to whom the city was subject were searching for books to build up the library in Pergamum, they hid the books underground in a kind of trench. But much later, when the books had been damaged by moisture and moths, their descendants sold them to Apellicon of Teos for a large sum of money, both the books of Aristotle and those of Theophrastus.

But Apellicon was a bibliophile rather than a philosopher; and therefore, seeking a restoration of the parts that had been eaten through, he made new copies of the text, filling up the gaps incorrectly, and published the books full of errors. The result was that the earlier school of Peripatetics who came after Theophrastus had no books at all, with the exception of only a few, mostly exoteric works, and were therefore able to philosophize about nothing in a practical way, but only to talk bombast about commonplace propositions, whereas the later school, from the time the books in question appeared, though better able to philosophize and Aristotle-ize, were forced to call most of their statements probabilities, because of the large number of errors.

Rome also contributed much to this; for, immediately after the death of Apellicon, Sulla, who had captured Athens, carried off Apellicon’s library to Rome, where Tyrannion the grammarian, who was fond of Aristotle, got it in his hands by paying court to the librarian, as did also certain booksellers who used bad copyists and would not collate the texts – a thing that also takes place in the case of other books that are copied for selling, both here and at Alexandria. However, this is enough about these men.”

And, continuing the same story, the following is from ‘Sylla’, by Plutarch:

“Having set out from Ephesus with the whole navy, he came the third day to anchor in the Piraeus. Here he was initiated in the mysteries, and seized for his use the library of Appelicon the Teian, in which were most of the works of Theophrastus and Aristotle, then not in general circulation.

When the whole was afterwards conveyed to Rome, there, it is said, the greater part of the collection passed through the hands of Tyrannion the grammarian, and that Andronicus the Rhodian, having through his means the command of numerous copies, made the treatises public, and drew up the catalogues that are now current. The elder Peripatetics appear themselves, indeed, to have been accomplished and learned men, but of the writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus they had no large or exact knowledge, because Theophrastus bequeathing his books to the heir of Neleus of Scepsis, they came into careless and illiterate hands.”

Let us repeat this story, in summary – Aristotle’s and Theophrastus’s writings were discovered by Apellicon about 100 BC, taken to Rome by Sulla in 86 BC, and after editing, were published by Andronicus in 60 BC.

In other words, NO ONE was able to read Aristotle’s works until more than 250 years after his death! Then, they were published in Latin, in Rome, and after that we were taught of the greatness of Aristotle – who was to be the philosopher of the Roman Empire!

Subsequently, we were taught of the different ‘schools’ of philosophy, when in 176 AD (over 200 years later), the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius established the Four Chairs of Philosophy at Athens – the Epicurians (of Epicurus), the Stoics (of Zeno of Citium), the Peripatetics (of Aristotle), and the Academics. However, the Academics were not followers of Plato’s Academy, but were followers of the ‘New Academy’ – or, more correctly, the Skeptics (of Pyrrho). But for a look at the real Plato, what could we read, except this story that the Skeptics were the followers of Plato?

We shall be forever indebted to Augustine, who tells of his reading of Cicero, and of his work to unravel the difference between the real Academy of Plato, and the so-called New Academy of the Skeptics, and thus exposes the fraud of the four, different but equal, schools of philosophy of the Roman Empire.

[For a look at the Epicurians, one could read Lucretius’ ‘On the nature of the universe’. For a look at the Stoics, one could read the ‘Meditations’ of Marcus Aurelius, himself. For a look at the Peripatetics, one could read the complete works of Aristotle. For a look at the Skeptics, one could read Sextus Empericus’ ‘Outlines of Pyrrhonism’.]

And so, we have the skeptics, and peripatetics, and stoics, and epicurians, as the accepted philosophies of the Roman Empire – but in reality, all were just different versions of the ‘sophists’, as we find ourselves looking at a larger historical outcome of this great dispute.

The following is from ‘The Secrets Known Only to the Inner Elites’, by Lyndon LaRouche:

“Through three millennia of recorded history to date, centered around the Mediterranean, the civilized world has been run by two, bitterly opposed elites, the one associated with the faction of Socrates and Plato, the other with the faction of Aristotle. During these thousands of years … both factions’ inner elites maintained in some fashion an unbroken continuity of organization and knowledge through all of the political catastrophes which afflicted each of them in various times and locales.”

Next, I think that we should look deeper into this dispute between Plato and Aristotle.

[ next week – Part 7 – Plato’s Poetic Principle ]