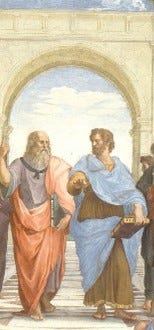

THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL of ATHENS

Part 7 - Plato’s Poetic Principle

To look into this dispute between Plato and Aristotle, we should look at the existence of ‘ideas’, that Plato called the ‘forms’, and that Aristotle claims don’t exist!

The following is from ‘Metaphysics’, by Aristotle:

“The theory of Forms occurred to those who enunciated it because they were convinced as to the true nature of reality by the doctrine of Heraclitus, that all sensible things are always in a state of flux; so that if there is to be any knowledge or thought about anything, there must be certain other entities, besides sensible ones, which persist. For there can be no knowledge of that which is in flux.

Further, of the ways in which we prove that the Forms exist, none is convincing;

But, further, all other things cannot come from the Forms in any of the usual senses of ‘from’. And to say that they are patterns and the other things share in them is to use empty words and poetical metaphors.

Nor, indeed, can any Idea be defined; for the Idea is an individual, as they say, and separable; and the formula must consist of words, and the man who is defining must not coin a word, because it would not be comprehensible.”

Plato says that this ‘idea’ has a physical existence, though not perceived by our senses, but exists nonetheless – that although you can’t see, hear, smell, taste or touch an idea, and that it has no sensual perceptions, but that it nonetheless has a real physical existence, that can be measured, but in a different sense.

If we wish to look deeper into this dispute between Plato and Aristotle, and whether an ‘idea’ has existence or not, I think that we should return to Augustine.

In his dialogue ‘Answer to the Skeptics’, Augustine writes that:

“Furthermore, I know for certain that this world of ours has its present arrangement either from the nature of bodies or from a foresight of some kind. I am also certain that either it always was and always will be, or it had a beginning and will never end, or it existed before time and will have an end, or it had a beginning and will not last forever.”

Here, Augustine has given us a simple picture of the essence of the philosophy of ancient Greece. In their discussions and arguments concerning ‘being’, or ‘not-being’, Augustine writes that there are four possible ideas, or forms, of ‘being’.

First of all, the third form – that which has no beginning but has an end – Augustine says is impossible, since if it has no beginning, then it does not have any characteristic that could cause it to have an end.

And, the fourth form – that which has a beginning and has an end – we call the ‘created’, or the ‘finite’, that we see as all the phenomenon of nature in the universe, including ourselves.

And, the first form – that which has no beginning and has no end – we call ‘God’, or the ‘infinite’. Although, it is hard for us to truly conceptualize the ‘infinite’, we can see it in a certain way, by knowing what it is not.

And, lastly, the second form – that which has a beginning but has no end – we call the ‘universe’, or the ‘soul’ or the ‘idea’, or we call the ‘trans-finite’.

This is the great debate in Greek philosophy, and I think in other cultures too – there has to be this connection between the finite and the infinite, between the mortal world and the divine world. Or else we get trapped in the Eleatic paradox of the one and the many.

In ‘Hymn to Apollo’, the Greek poet Homer says that Apollo was this envoy between the gods and man:

“Let there be given me my lov'd lute and bow,

I'll prophesy to men; and make them know

Jove's perfect counsels.”

And this is the great debate between Plato and Aristotle – the existence of the idea! But, how and where can we find this ‘idea’ of Plato’s?

In ‘Plato and the New Political Science’, LaRouche writes that:

“Ignorant opinion concerning scientific education assumes that students progress by mastering proven theories, procedures, and so forth – something analogous to stuffing programs into a digital computer system. This is not the case. Students learn scientific method through successes and failures in problem solving. They ‘guess’ answers to problems from the launching point of knowledge already given to them; those guesses which lead to successful solutions then serve as the basis for the mind's informing itself of what kinds of assumptions and methods lead to successful hypotheses …

By hypothesis we mean those methods of scientific guessing which can be relied upon to produce a usually fruitful result in empirical practice.”

Let us take a look at this ‘idea’ of ‘guessing’, using an excerpt from a short story of our friend, Edgar Allan Poe, entitled ‘Mellonta Tauta’.

But in all ages the great obstacles to advancement in Art have been opposed by the so-called men of science. To be sure, our men of science are not quite so bigoted as those of old:

“Oh, I have something so queer to tell you on this topic. Do you know that it is not more than a thousand years ago since the metaphysicians consented to relieve the people of the singular fancy that there existed but two possible roads for the attainment of Truth! Believe it if you can! It appears that long, long ago, in the night of Time, there lived a Turkish philosopher (or Hindoo possibly) called Aries Tottle. This person introduced, or at all events propagated what was termed the deductive or a priori mode of investigation. He started with what he maintained to be axioms or ‘self-evident truths’, and thence proceeded ‘logically’ to results. His greatest disciples were one Neuclid, and one Cant. Well, Aries Tottle flourished supreme until advent of one Hog, surnamed the ‘Ettrick Shepherd’, who preached an entirely different system, which he called the a posteriori or inductive. His plan referred altogether to Sensation. He proceeded by observing, analyzing, and classifying facts – instantiae naturae, as they were affectedly called – into general laws. Aries Tottle’s mode, in a word, was based on noumena; Hog’s on phenomena. Well, so great was the admiration excited by this latter system that, at its first introduction, Aries Tottle fell into disrepute; but finally, he recovered ground and was permitted to divide the realm of Truth with his more modern rival. The savans now maintained the Aristotelian and Baconian roads were the sole possible avenues to knowledge. ‘Baconian’, you must know, was an adjective invented as equivalent to Hog-ian and more euphonious and dignified.

Now, my dear friend, I do assure you, most positively, that I represent this matter fairly, on the soundest authority and you can easily understand how a notion so absurd on its very face must have operated to retard the progress of all true knowledge – which makes its advances almost invariably by intuitive bounds. The ancient idea confined investigations to crawling; and for hundreds of years so great was the infatuation about Hog especially, that a virtual end was put to all thinking, properly so called. No man dared utter a truth to which he felt himself indebted to his Soul alone. It mattered not whether the truth was even demonstrably a truth, for the bullet-headed savans of the time regarded only the road by which he had attained it. They would not even look at the end. ‘Let us see the means’, they cried, ‘the means’! If, upon investigation of the means, it was found to come under neither the category Aries (that is to say Ram) nor under the category Hog, why then the savans went no farther, but pronounced the ‘theorist’ a fool, and would have nothing to do with him or his truth …

Now I do not complain of these ancients so much because their logic is, by their own showing, utterly baseless, worthless and fantastic altogether, as because of their pompous and imbecile proscription of all other roads of Truth, of all other means for its attainment than the two preposterous paths – the one of creeping and the one of crawling – to which they have dared to confine the Soul that loves nothing so well as to soar.

By the by, my dear friend, do you not think it would have puzzled these ancient dogmaticians to have determined by which of their two roads it was that the most important and most sublime of all their truths was, in effect, attained? I mean the truth of Gravitation. Newton owed it to Kepler. Kepler admitted that his three laws were guessed at – these three laws of all laws which led the great Inglitch mathematician to his principle, the basis of all physical principle – to go behind which we must enter the Kingdom of Metaphysics. Kepler guessed – that is to say imagined. He was essentially a ‘theorist’ – that word now of so much sanctity, formerly an epithet of contempt. Would it not have puzzled these old moles too, to have explained by which of the two ‘roads’ a cryptographist unriddles a cryptograph of more than usual secrecy, or by which of the two roads Champollion directed mankind to those enduring and almost innumerable truths which resulted from his deciphering the Hieroglyphics.”

And so, we see that to truly know something, we must discover its ‘idea’, and not by ‘inducing’ or ‘deducing’, but by ‘adducing’ or ‘guessing’ at its cause or principle – ‘guessing’ at its hieroglyphics - guessing to adduce an ‘idea’.

In ‘Plato and the New Political Science’, LaRouche continues:

“What the future will be, can be adduced implicitly from the characteristic features of those assumptions which are variously explicitly and unwittingly embedded in the prevailing weight of individual decisions. If we are not to play roulette with the fate of present and future generations, if we are assured meaning to our individual living and, having lived, we must know that we have discovered and are self-governed by efficient knowledge of the sets of principles which do in fact govern the historical process. It is so to determine the present and future that we devote ourselves to rigorous study of the past. We cannot adduce efficient principles from the idiosyncrasies of the social order as defined by the here and now. We cannot attribute wisdom to mere prevailing opinions of the present, whether scholarly or vulgar. We must know those principles which transcend all “heres and nows”, an achievement which can be effected by no other method than the poetic principles employed by Plato.”

I guess that this has shown us how Plato, who believed in the existence of ideas, left us his dialogues, and why Aristotle, who didn’t believe in ideas, didn’t leave us any dialogues or poems.

Now, we can move on, past the dispute of Plato and Aristotle, and to see those persons who came after Plato.

[next week – part 8 – the followers of Plato ]