THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL of ATHENS

Part 3- the Eleatic Paradox

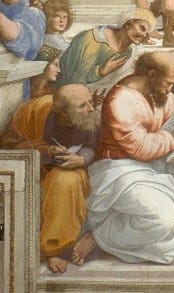

Next, if we look to the left of Pythagoras, we see a person behind him who is looking over Pythagoras’s shoulder at his writing, and who also seems to be copying or writing in his own book (actually it looks a single piece of paper). And this I think, could be Parmenides, who lived from approximately 515 to 450 BC, and who wrote one book – ‘a poem in hexameter verse, addressed to his pupil Zeno’.

[Note: The fragments of Parmenides can be found in ‘Ancilla To The Pre-Socratic Philosophers’, translated by Kathleen Freeman (Harvard University Press) from the Vorsokratiker Fragmente by Hermann Diels]

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Parmenides, the son of Pyres, and a citizen of Velia (Elea), was a pupil of Xenophanes. And Theophrastus, in his Abridgement, says that he was also a pupil of Anaximander. However, though he was a pupil of Xenophanes, he was not afterwards his follower; but he attached himself to Aminias, and Diochartes the Pythagorean, as Sotion relates, which last was a poor but honorable and virtuous man. And he it was whose follower he became …

II. He was the first person who asserted that the earth was of a spherical form; and that it was situated in the centre of the universe. He also taught that there were two elements, fire and earth; and that one of them occupies the place of the maker, the other that of the matter. He also used to teach that man was originally made out of clay; and that they were composed of two parts, the hot and the cold; of which, in fact, everything consists. Another of his doctrines was, that the mind and the soul were the same thing …

III. … And he used to say that argument was the test of truth; and that the sensations were not trustworthy witnesses.”

So, it seems that Parmenides was a follower of Pythagoras, and so I think that this person should be Parmenides.

Plato wrote a dialogue called ‘Parmenides’, that tells the story of Socrates, when he was a young man and he met Parmenides and his student, Zeno, and that tells of their discussion of the paradox of Parmenides’ idea about the ‘One and the Many’.

And Plato wrote another dialogue called the ‘Sophist’, where the main speaker was a stranger from Elea – ‘one of the followers of Parmenides and Zeno, and a real philosopher’. And in the dialogue the Stranger said that:

“It seems to me that Parmenides and all who ever undertook a critical definition of the number and nature of realities have talked to us rather carelessly. Every one of them seems to tell us a story, as if we were children.

One says that there are three principles, that some of them are sometimes waging a war with each other, and sometimes become friends and marry and have children and bring them up; and another says that there are two, wet and dry, or hot and cold, which he settles together and unites in marriage.

And the Eleatic sect in our region, beginning with Xenophanes and even earlier, have told their story that all things, as they are called, are really one. Then some Ionian and later some Sicilian Muses reflected that it was safest to combine the two tales and to say that being is many and one, and is (or are) held together by enmity and friendship.”

[The Stranger here is talking about philosophers like Pherecydes, Xenocrates, Heraclitus and Empedocles.]

But the Stranger said that thinking of existence in this way, gives us ‘countless problems’ involving ‘infinite difficulties’, and he referred to another group, saying:

“An indeed there seems to be a battle like that of the gods and the giants going on among them, because of their disagreement about existence.

Some of them drag down everything from heaven and the invisible to earth, actually grasping rocks and trees with their hands; for they lay their hands on all such things and maintain stoutly that that alone exists which can be touched and handled; for they define existence and body, or matter, as identical, and if anyone says that anything else, which has no body, exists, they despise him utterly, and will not listen to any other theory than their own.”

[The Stranger is here referring to the philosophers of sense-certainty, like Leucippus and Democritus.]

And the Stranger tried to solve this conflict ‘of the gods and the giants’, by reminding us about one of the things that Parmenides had said, that:

“Never let this thought prevail, saith he, that not-being is;

But keep your mind from this way of investigation.”

And the Stranger wondered ‘if, then, not merely for the sake of discussion, or as a joke, but seriously’ how would a student of Parmenides answer the question - if ‘not-being’ is? And then the Stranger, with a young Theaetetus, went through a serious re-working of the ‘Parmenides’ dialogue, with the added change of admitting the existence of ‘not-being’ – in order to ‘adduce for this purpose a certain paradigm’.

The exercise of this kind of reasoning is best explained to us by Lyndon LaRouche, who wrote that:

“The first rule in the method of Plato's Socratic dialogues, is that any deductive reasoning is nothing but a giant tautology, from beginning to end. The only kind of mental activity which is possible within the limits of deductive reasoning, is to prove that a particular theorem is logically consistent with the original axiomatic assumptions of that deductive system. Therefore, within the bounds of deductive reasoning, it is impossible to prove, adequately, whether or not the system as a whole is sane or insane.

Thinking deductively, is not insanity in and of itself. On the contrary, as long as you limit deductive thinking to the business of checking the consistency of theorems, you would be as insane as a typical liberal, if you did not employ deductive rigor. Deductive reasoning becomes paranoid, only if you carry it to the extreme, of rejecting Plato's Socratic method. The essence of Socratic reasoning, is the recognition, that the best deductive reasoning can do no better than to generate gigantic tautologies. In Socratic method, we use deductive reasoning; but we stand outside it. We look at the entirety of any deductive reasoning as a gigantic tautology; we take the entirety of that tautology as a single object of thought. You may be asking yourself, how is it possible to see an entire system of deductive thinking as an indivisible unit of thought? The answer is a simple one. Take two equally consistent systems of deductive thinking. Ask yourselves: What is it, which distinguishes one of these two systems from the other? The answer is, ‘a difference of the axiomatic assumptions of the one, from the set of axioms upon which the other is premised’.”

[from ‘SDI & Mars Colonization: Examples of the Way in Which Science Performs as an Expression of The Absolute Good’, August 1986, by Lyndon LaRouche]

And so, by changing one of the necessary conditions of Parmenides’ argument (that is, by changing necessity) they adduced – not deduced or induced, and by adducing a new paradigm (that is, by hypothesizing a new idea) they were able to solve their problem of discovering the essence of the sophist.

And next, if we look to the right of Parmenides, we see another person who is also looking over the shoulder of Pythagoras at what he is writing, but who is not writing anything, only looking.

And I’ve tried many times to think about who this person could be, but just as many times, I couldn’t come up with anyone appropriate, because this person is different from the others in that scene. He does not have a beard, but only has a moustache, and is wearing a turban on his head, that none of the others are wearing. It’s as if he may not be like them or may not be from there.

And so at first I thought that maybe he could be a stranger like our Elean stranger in Plato’s ‘Sophist’ dialogue.

But maybe, with his different appearance and dress, he could be an Arab or Muslim! Because with the fading away of the study of Greek philosophy at the end of the Roman Empire, it was the scholars and teachers of the ‘Islamic Renaissance’ that preserved the writings of the Greek philosophers.

A project of collecting and translating the Greek writings into Arabic was begun by Harun al-Rashid (an ally of Charlemagne) and they were kept in the library known as the ‘House of Wisdom’. Some of these writings and commentaries – i.e. Al-Farabi’s commentaries on the dialogues of Plato, ‘The Philosophy of Plato’, would find their way from these intellectual centres of Islam, like Toledo, into Europe. Until the great translation project of the 15th century in Florence, Italy – to translate the Greek philosophers into Latin, it was the ‘House of Wisdom’ that kept alive the ideas of the Greek philosophers.

And so I think that this person should be a ‘messenger from the House of Wisdom’.

In this first scene of the pre-Socratic philosophers, we can see Thales, Heraclitus, Pythagoras, Parmenides and a ‘messenger’. And also we can see 4 others - one who is holding the slate for Pythagoras and looking at another who is behind Parmenides, one is who behind Thales and one who is behind the ‘messenger’, who are both looking out as us, the audience.

Next, we will leave this first scene of the pre-Socratic philosophers, and shift our attention to those who are standing above them, on the top of the stairs – the Greek philosophers who came after them.

[next week - part 4 - the Sophists]