THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL OF ATHENS

Part 8 – the Followers of Plato

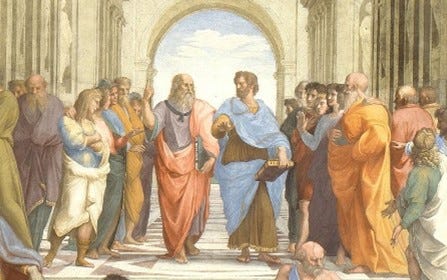

Now, we should try to look at the painting to try to figure out who came after Plato. According to Diogenes Laertius, nineteen of Plato’s many students are listed as disciples – 17 men and 2 women – and I think it’s very important that it’s shown that women were permitted to enter Plato’s Academy.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius, in ‘Life of Plato’:

“XXXI. His disciples were Speusippus the Athenian, Xenocrates the Chalcedon, Aristotle the Stagirite, Philip of Opus, Histiaeus of Perinthus, Dion of Syracuse, Amyclus of Heraclea, Erastus and Coriscus of Sceptos, Timolaus of Cyzicus, Eudon of Lampsacus, Pithon and Heraclides of Aemus, Hippothales and Callipus, Athenians, Demetrius of Amphipolis, Heraclides of Pontus, and numbers of others, among whom there were also two women, Lasthenea of Mantinea, and Axiothea of Phlius, who used even to wear man's clothes …”

If we now look back at Plato, we see that around him are many people, standing and walking – to the left of Plato, five people are standing and behind them, two more are walking towards us; to the right of Plato, seven people are standing and two more behind them are walking away from us. These sixteen people, who are watching and listening to this dispute between Plato and Aristotle, should be the students of Plato.

So, of these nineteen disciples, we can see sixteen who are standing and walking around him. There should be three more of his followers somewhere.

Besides Aristotle, who we’ve already met, only two others of Plato’s students are talked about by Diogenes Laertius – Speusippus and Xenocrates – both of whom became head of the Academy after Plato.

Looking to the right of Plato and Aristotle, is a young person, leaning against a pillar in the corner of the building, and with one leg lifted and crossed over the other leg, he is using this leg to hold up his book, while he writes. This could be Speusippus.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“II. And he (Plato) was succeeded by Speusippus, the son of Eurymedon, and a citizen of Athens, of the Myrrhinusian burgh, and he was the son of Plato's sister Potone.

III. He presided over his school for eight years, beginning to do so in the hundred and eighth olympiad. And he set up images of the Graces in the temple of the Muses, which had been built in the Academy by Plato.

IV. And he always adhered to the doctrines which had been adopted by Plato, though he was not of the same disposition as he.

VI. He was the first man, as Diodorus relates in his first book of his Commentaries, who investigated in his school what was common to the several sciences; and who endeavoured, as far as possible, to maintain their connection with each other.

VII. But he became afflicted with paralysis, and sent to Xenocrates inviting him to come to him, and to become his successor in his school.

XI. He left behind him a great number of commentaries, and many dialogues.”

Because this person is shown with one leg crossed over the other in order to hold his book, and because it was said that Speusippus wrote a great number of commentaries and dialogues, and that he later became paralyzed, I think that this should be Speusippus.

And, looking to the right of Speusippus, is someone who is lazily leaning on the pillar, and looking over the shoulder of Speusippus while he is writing. This could be Xenocrates.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“1. Xenocrates was the son of Agathenor, and a native of Chalcedon. From his early youth he was a pupil of Plato, and also accompanied him in his voyages to Sicily.

II. He was by nature of a lazy disposition, so that they say that Plato said once, when comparing him to Aristotle, – ‘The one requires the spur, and the other the bridle.’

III. In other respects Xenocrates was always of a solemn and grave character, so that Plato was continually saying to him, – ‘Xenocrates, sacrifice to the Graces.’ And he spent the greater part of his time in the Academy, and whenever he was about to go into the city, they say all the turbulent and quarrelsome rabble in the city used to make way for him to pass by …

IV. And he was a very trustworthy man; so that, though it was not lawful for men to give evidence except on oath, the Athenians made an exception in his favour alone.

VI. … To one who had never learnt music, or geometry, or astronomy, but who wished to become his disciple, he said, ‘Be gone, for you have not yet the handles of philosophy.’ … And when Dionysius said to Plato that someone would cut off his head, he, being present, showed his own, and said, ‘Not before they have cut off mine.’

IX. And he left behind him a great number of writings, and books of recommendation, and verses … (including six books on Mathematics, five books on Geometry, one on Arithmetic, and six on Astronomy).

XI. He succeeded Speusippus, and presided over the school for twenty-five years.”

Because this person is lazily leaning on the pillar and watching Speusippus, and because it was said that Xenocrates had a lazy disposition, and that he came to Speusippus to succeed him as head of the Academy, I think this should be Xenocrates.

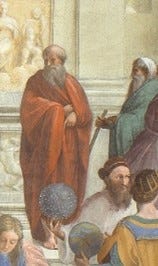

Next, to the right of Speusippus and Xenocrates, are two persons who are looking back towards them, but it seems are somewhat unhappy.

The person to the right, wearing a scarf on his head and carrying a stick or staff, I think could be Antisthenes, and the person standing to the left, I think could be Diogenes the Cynic.

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Antisthenes was an Athenian, the son of Antisthenes. And he was said not to be a legitimate Athenian … for he was thought to have had a Thracian mother … And he himself, when disparaging the Athenians who gave themselves great airs as having been born out of the earth itself, said that they were not more noble as far as that went than snails and locusts.

II. Originally he was a pupil of Gorgias the rhetorician; owing to which circumstance he employs the rhetorical style of language in his Dialogues ... Afterwards, he attached himself to Socrates, and made such progress in philosophy while with him, that he advised all his own pupils to become his fellow pupils in the school of Socrates. And as he lived in the Piraeus, he went up forty furlongs to the city every day, in order to hear Socrates, from whom he learnt the art of enduring, and of being indifferent to external circumstances, and so became the original founder of the Cynic school.

V. … He used to insist that virtue was a thing which might be taught; also, that the nobly born and virtuously disposed, were the same people; for that virtue was of itself sufficient for happiness, and was in need of nothing, except the strength of Socrates. He also looked upon virtue as a species of work, not wanting many arguments, or much instruction; and he taught that the wise man was sufficient for himself; for that everything that belonged to anyone else belonged to him.

VI. He used to lecture in the Gymnasium, called Cynosarges, not far from the gates; and some people say that it is from that place that the sect got the name of Cynics.

VIII. … He was the original cause of the apathy of Diogenes, and the temperance of Crates, and the patience of Zeno, having himself, as it were, laid the foundations of the city which they afterwards built.”

The following is from ‘Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius:

“I. Diogenes was a native of Sinope, the son of Tresius, a money-changer. And Diocles says that he was forced to flee from his native city, as his father kept the public bank there, and had adulterated the coinage.

II. And when he came to Athens, he attached himself to Antisthenes; but as he repelled him, because he admitted no one; he at last forced his way to him by his pertinacity. And once, when he raised his stick at him, he put his head under it, and said, ‘Strike, for you will not find any stick hard enough to drive me away as long as you continue to speak.’ And from this time forth he was one of his pupils; and being an exile, he naturally betook himself to a simple mode of life.

III. And when, as Theophrastus tells us, in his Megaric Philosopher, he saw a mouse running about and not seeking for a bed, nor taking care to keep in the dark, nor looking for any of those things which appear enjoyable to such an animal, he found a remedy for his own poverty. He was, according to the account of some people, the first person who doubled up his cloak out of necessity, and who slept in it; and who carried a wallet, in which he kept his food; and who used whatever place was near for all sorts of purposes, eating, and sleeping, and conversing in it ... Being attacked with illness, he supported himself with a staff; and after that he carried it continually, not indeed in the city, but whenever he was walking in the roads, together with his wallet …

IV. He was very violent in expressing his haughty disdain of others. He said that the school of Euclides was gall. And he used to call Plato’s discussions, disguise … He used also to ridicule him as an interminable talker … He used also to say, ‘That the musicians fitted their strings to the lyre properly, but left all the habits of their soul ill-arranged.’ And, ‘That mathematicians kept their eyes fixed on the sun and moon, and overlooked what was under their feet.’

VI. When Plato was discoursing about his ‘ideas’, and using the nouns ‘tableness’ and ‘cupness’; ‘I, O Plato!’ interrupted Diogenes, ‘see a table and a cup, but I see no tableness or cupness.’ Plato made answer, ‘That is natural enough, for you have eyes, by which a cup and a table are contemplated; but you have not intellect, by which tableness and cupness are seen.’

VIII. Music and geometry, and astronomy, and all things of that kind, he neglected, as useless and unnecessary.”

And because of Antisthenes’ s disparaging attitude to the Athenians, and Diogenes’s disdain of Plato, and of music and geometry, and because of Antisthenes holding the stick that he used to try to dissuade Diogenes, I think that these two persons should be Antisthenes and Diogenes, the first of the Cynics and Stoics.

Now, if we look to the right of Antisthenes, at the very edge of this second scene at the top of the stairs, we see two persons. One person (actually we only see his head) is looking down at the group of people at the bottom of the stairs, as if he is to be the announcer for that next scene.

And in front of him we see a second person, who seems to be rushing past the pillar and out of the scene, but whose left hand is wrapped around to his right side and whose head is turning to his right side too – as if he is trying to somehow turn himself around to look back over this second scene, before he leaves the stage.

Perhaps, these two announcers, one looking back and one looking forward, are telling us that if we want to get to the scene at the bottom of the stairs, we may have to leave the story of Diogenes Laertius, that seems to end at this point, and that if we go back to the followers of Plato, to Speusippus and Xenocrates, we could find a way forward.

Next, we will have to find a way to move on to that last scene at the bottom of the stairs (in the right foreground).

[ next week – part 9 - a way to the ‘Elements’ ]