Mathew Carey and the Rise of the 'American System'

Part 2 - The Fight for a National Bank

On December 5th 1815, President James Madison sent a Message for the opening of the 14th Congress, stating that because of ‘the embarrassments arising from the want of an uniform National currency’ and of the need for ‘the revival of the public debt’, ‘the probable operation of a National Bank will merit consideration’; that ‘in adjusting the duties on imports, to the object of revenue, the influence of the tariff on manufactures will necessarily present itself for consideration’; and that ‘among the means of advancing the public interest, the occasion is a proper one for recalling the attention of Congress to the great importance of establishing throughout our country the roads and canals which can be best executed under the national authority.’

A National Bank

What was being proposed ‘for consideration’ was – a National Bank, a protective tariff, and internal improvements!!! While realizing the national economic crisis that was created both during and after the war, Madison however, was not about to adopt a Hamiltonian solution – but a Jeffersonian version of one.

Although Madison hadn’t agreed to the adoption of the First National Bank – but had agreed to a compromise whereby, in exchange for the location of the Capital to the District of Columbia, he and Jefferson accepted Hamilton’s proposal for the federal government assumption of the States’ war debt – and since these debts subsequently became the basis of the First National Bank, he could un-hypocritically propose the ‘consideration’ of a Second National Bank

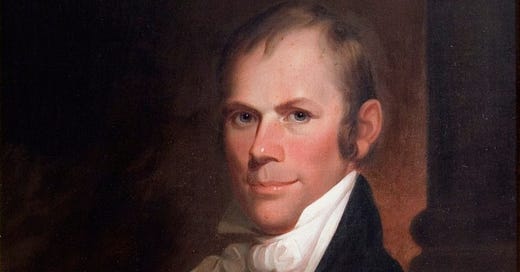

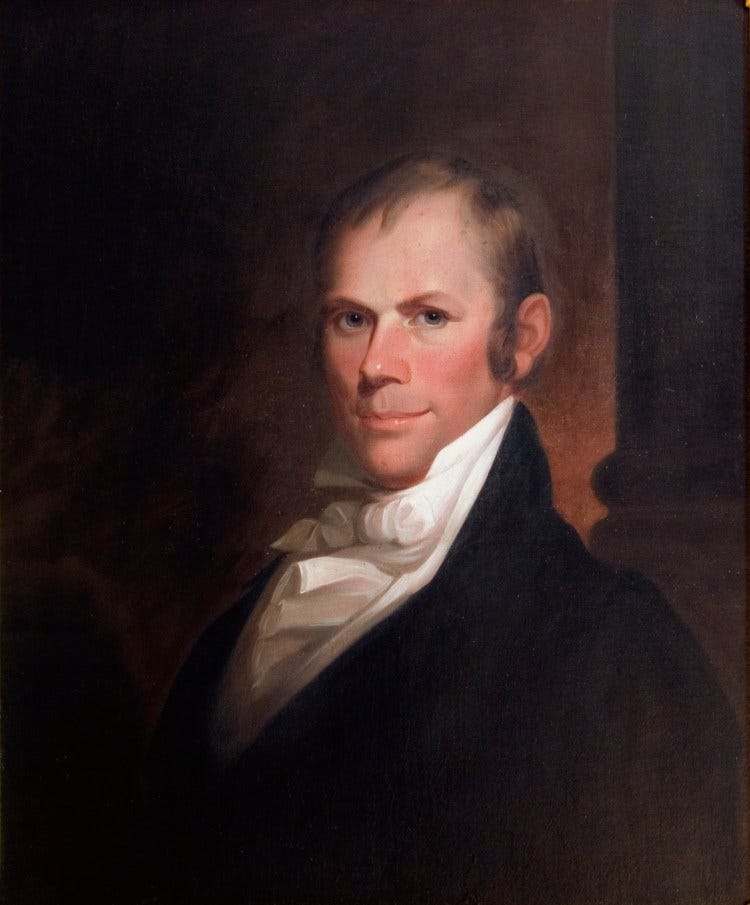

The effects on the American economy, during the war of 1812-1814, had proved Carey to have been right, and he became one of the leading pamphleteers in favour of the second Bank of the United States – to be established by some of the very men who had defeated the first National Bank, including Henry Clay.

In 1810, Clay had been appointed to the United States Senate by the Kentucky Legislature, and (as he says):

“he was induced to oppose the renewal of the charter to the old Bank of the United States by three general considerations.

The 1st was that he was instructed to oppose it by the Legislature of the State … although the two late Senators from this State, as well as the present senators, voted for a national bank.

The next consideration … was that he believed that the corporation had, during a portion of the period of its existence, abused its powers, and had sought to subserve the views of a political party …

A 3rd consideration … was, that as the power to create a corporation, such as was proposed to be continued, was not specifically granted in the Constitution, and did not then appear to him to be necessary to carry into effect any of the powers which were specifically granted, Congress was not authorized to continue the bank.”

But, Clay supported the bill for the Second National Bank because:

“a general suspension of species payment had taken place, and this had led to a train of consequences of the most alarming nature … about 300 banking institutions, enjoying in different degrees the confidence of the public, shaken as to them all, under no direct control of the general government, and subject to no actual responsibility to the State authorities.

These institutions were emitting the actual currency of the United States; a currency consisting of a paper, on which they neither paid interest nor principal, while it exchanged for the paper of the community, on which both were paid … they were no longer competent to assist the treasury in either of the great operations of collection, deposit, or distribution of the public revenues …

Considering, then, that the state of emergency … threatened general distress, if it did not ultimately lead to convulsion and subversion of the government; it appeared to him to be the duty of Congress to apply a remedy, if a remedy could be devised. A national bank … was proposed as that remedy.”

[from ‘Address to his Constituents’, June 3rd 1816]

While Clay had voted against the renewal of the First National Bank, but voted in favor of the Second National Bank, his reasons for supporting the Bank hadn’t changed – as can been seen in his speech on Domestic Manufactures on April 6th 1810, and in his speech on Internal Improvements on February 4th 1817.

The Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Dallas, sent a report to Congress on a plan for a National Bank. After various amendments – to reduce the capital of the Bank, to stop Government subscription to the Bank, to stop Government appointment of five Bank directors, and to prohibit a branch unless accepted by that State’s law – were defeated, the bill passed the House by a close vote (80 to 71), and the Senate (22 to 12).

Internal Improvements

During an earlier 1806-07 session of Congress, resolutions were introduced for internal improvements:

– for a road from Cumberland, Maryland to the State of Ohio (a bill was passed to appropriate $250,000),

– for a canal at the Ohio rapids (the resolution was introduced by Senator Clay, and a bill was passed to appoint 3 commissioners to examine its practicality), and,

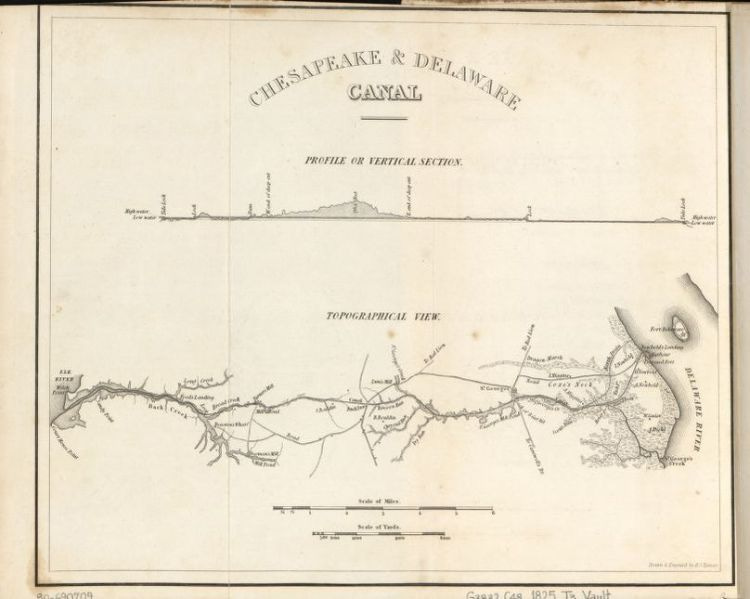

– for the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal (a bill was debated but postponed until the next session).

Note: Thomas Gilpin Sr. (along with Dr. Benjamin Franklin) had been part of a committee of the American Philosophical Society in 1769, that was set up to study a canal to link the Chesapeake and Delaware bays. Joshua Gilpin would become a promoter, and a director of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Company in 1803. William Gilpin was the grandson of Thomas Sr., and the son of Joshua.

For this full story, see William Gilpin and the First World Landbridge

It was during the debate on the Chesapeake and Delaware canal, that Senator John Quincy Adams proposed a resolution –

“that the Secretary of the Treasury be directed to prepare, and report to the Senate at their next session, a plan for the application of such means as are constitutionally within the power of Congress, to the purposes of opening roads, for removing obstructions in rivers and making canals; together with a statement of the undertakings of that nature now existing within the United States, which as objects of public improvements, may require and deserve the aid of Government.”

Although Adams’ resolution was blocked, it was then re-introduced by Senator Thomas Worthington (Ohio) with an addition – that:

“and, also, a statement of works of the nature mentioned which have been commenced, the progress which has been made in them, and the means and prospect of their being completed; and all such information as, in the opinion of the Secretary, shall be material, in relation to the objects of this resolution.”

The resolution passed by a vote of 22 to 3 on March 2nd 1807, and the Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, would present his report the following next year on April 6th 1808. Although the report is called Gallatin’s Report, it should really be called the Latrobe Report.

In 1804, Benjamin Latrobe had been selected to be the engineer to design and construct the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, until it was stopped, due to lack of funds in December 1805. In response to the petition to Congress, from Joshua Gilpin and the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Company for a land grant in order to continue the work, came that bill, and subsequently, that resolution of Adams and Worthington.

“Gallatin sent out questionnaires to custom collectors throughout the United States concerning the canals and turnpike roads which had been built, were being constructed, or were still in the planning stages in their respective districts. In addition, he asked Robert Fulton and Benjamin Latrobe for more general information of roads and canal … Not only did Latrobe compose a thirty page essay on canals and river improvements in America but he met with Gallatin at least every other day during March 1808 when the secretary was sorting out the masses of information that had poured into Washington from canal and turnpike companies across the country and compiling his report to the Senate.”

[from ‘Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Revival of the Gallatin Plan of 1808’, by Lee Formwalt]

Adams reported the printing of 1200 copies of the report, including the essays of Latrobe and Fulton.

During the debate on the National Bank, Bolling Hall (Georgia) proposed a resolution to apply ‘the bonus arising to the Government from the incorporation of the Bank to the internal improvement of the country’.

John Calhoun (South Carolina) supported the idea, but was afraid that its adoption:

“might drive off some who would otherwise support the bill – unfortunately for us, there was not a unanimous feeling in favor of internal improvement, some believing this not a proper time to commence that work; and such a provision might deprive the bill of some friends, which at present was the main object of his solicitude.”

Hall “thought this the most proper moment for commencing the great work of internal improvement; but if he thought his amendment would draw off any support from the bill, he would not urge it.”

But, in the next session of Congress, Calhoun would propose a bill (based on Hall’s amendment) to establish a ‘permanent fund for internal improvements’ from the Government’s share of the dividends of the National Bank and the bonus for its charter. Clay noted that:

“he had long thought that there were no two subjects which would engage the attention of the National Legislature more worthy of its deliberate consideration, than those of internal improvements and domestic manufactures.”

The bill was narrowly passed by the House, 86 to 84, and by the Senate 20 to 15.

Previously, in President Jefferson’s Message to Congress (November 8th 1808) he stated his economic outlook that:

“the probable accumulation of the surpluses of revenue beyond what can be applied to the payment of debt, whenever the freedom and safety of our commerce shall be restored, merits the consideration of Congress … shall it not rather be appropriated to the improvements of roads, canals, rivers, education, and other great foundations of prosperity and union, under the powers which Congress may already possess, or such amendment of the Constitution as may be approved by the States?’

Since Jefferson had proposed that in times of peace, and once the public debt was paid off, a surplus could be spent on internal improvements, so then Madison would only venture as far as Jefferson’s interpretation of the Constitution would allow him to go.

On the very last day of his presidency, March 3rd 1817, Madison vetoed the bill for the fund for internal improvements, on the grounds that it was unconstitutional – that:

“… ‘the power to regulate commerce among the several states’ cannot include the power to construct roads and canals, and to improve the navigation of water-courses, in order to facilitate, promote, and secure such a commerce … ‘to provide for the common defense and general welfare’ would be contrary to the established and consistent rules of interpretation … (and) would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation, instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them.”

The House voted 60 to 56 to support the bill – but it wasn’t enough to over-ride the President’s veto.

Note: The federal funding and promotion of needed internal improvements to provide for the general welfare of the nation, would have to await the election of President John Quincy Adams.

[next week - part 3 - The Fight for a Protective Tariff]