Mathew Carey and the Rise of the ‘American System’

Part 3 - The Fight for a Protective Tariff

A Protective Tariff

Although Hamilton’s Report had proposed bounties as well as tariffs to protect new manufactures, Madison would propose the ‘consideration’ of a tariff for manufactures – but only as ‘an object of revenue’, in keeping with the Jeffersonian dogma, concerning which proportion of revenues came from direct taxes, and which came from duties on tariffs, while bearing in mind that paying off the public debt was paramount.

Carey would describe the problem in the country with this type of thinking concerning a protective tariff.

The following is from the Autobiography of Mathew Carey, that originally appeared in the New England Magazine, from Letter XXIII:

“From the commencement of our Government, a strong jealousy prevailed of the protection of manufactures, fostered and encouraged by those citizens engaged in commerce, particularly those connected with the importation of British manufactures, whether Americans or British agents. The latter description of persons were indefatigable in their efforts to promulgate those doctrines, so essentially promotive of their dearest interests. The leading papers in the commercial cities also took this ground. The general prevalence of these opinions is not, therefore, wonderful. Neither pains nor expense were spared to impress on the public mind, that the national prosperity depended almost altogether on commerce; that the protection of manufactures by duties on imposts was impolitic and unjust; that it sacrificed the interest of the many for the benefit of the few, by obliging the mass of our citizens to purchase domestic manufactures at a great advance, beyond the prices at which similar articles could be had from abroad; and that the imposition of duties on imports should be confined to the mere raising of revenue to meet the wants of Government …

So entirely and shamefully were we dependent on foreign nations for most essential necessities, that we were unable, during the operation of the nonintercourse law, to supply the Indians with blankets, due to them by treaty stipulation, to the amount of about $6,000, insomuch that the Secretary of War actually applied to Congress to modify the law, so as to enable him to import the blankets from Great Britain! A proper sequel to this miserable state of things is the important and disgraceful fact, that our soldiers suffered more, at some stages of the late war, by deficiency of clothing, than from the arms of the enemy.”

Secretary of the Treasury Dallas sent to Congress his report ‘on the subject of a general tariff of duties proper to be imposed on imported goods, wares, and merchandise’ that proposed –

“1st. the object of rising, by duties on imports and tonnage, the proportion of public revenue which must be drawn from that source;

2nd. the object of conciliating the various national interests, which arise from the pursuits of agriculture, manufactures, trade, and navigation’;

and 3rd. the object of rendering the collection of the duties convenient, equal, and certain.”

In 1812, all duties on imported goods were doubled – until one year after a peace with Great Britain.

For example, on the duty for imported woolen and cotton manufactures, while Dallas had recommended a ‘conciliating’ duty of 33 1/3%, the Committee of Ways and Means lowered the duty to 25% when it brought in the bill. Clay moved an amendment to increase the duty back to 33 1/3% on imported cotton, ‘to try the sense of the House as to the extent to which it was willing to go in protecting domestic manufactures’ and he spoke in favor of ‘a thorough and decided protection of ample duties’, but his motion was defeated (by 51 to 43). Clay then proposed to raise the duty from 25% to 30%, speaking on ‘the expediency of affording protection to our manufacturers’, and this motion carried (68 to 61).

But even this ‘compromise’ was opposed in Congress – by the spokesmen of the New England shipping interests, and of the Southern cotton and slave interests – both of whom preferred the policy of free-trade.

After much debate, Daniel Webster (New Hampshire) proposed to limit the 30% duty on imported cotton to only 2 years, a proposal from Clay of 3 years was defeated, and it was then agreed to a limit of 30% for 2 years, 25% for 2 years, and then 20%.

William Lowndes (South Carolina) next proposed to reduce that to simply 25% for 2 years and then to 20%, but Samuel Ingham’s (Pennsylvania) proposal of 25% for 3 years, 22 ½ for 1 year, and then 20% was agreed to.

Next, Martin Hardin (Kentucky) again proposed 25% for 2 years and Timothy Pickering (Massachusetts) argued that even that was unnecessary, but the House finally agreed to Hardin’s motion (84 to 60).

Thomas Gold (New York) asked ‘will you uphold the present manufactures of woollen and cotton, against the inundation of foreign fabrics, co-operating with the unexampled price of cotton, to their destruction?’ and he quoted from ‘Secretary Hamilton, one of the brightest stars in our political hemisphere, in his report to the House of Representatives, on manufactures, in the year 1791’. Samuel Smith (Maryland) then proposed a duty of 25% for 3 years, and the House voted narrowly, 79 to 71, in favor.

An approach based on the principles as outlined in Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures, would have placed a high tariff on all imported British (East India) cotton fabrics, in order to encourage and to protect the American cotton manufacturers (and, even to encourage the growth of cotton manufactures in the southern States!) – and thus, would have created a domestic market for the cotton produced by the southern States, so that the American cotton growers would not be entirely dependent on the foreign British market.

But this ‘conciliating’ compromised tariff left the manufacturers defenceless against the policies of the British Empire, and when the Empire cut back on its purchases of cotton from the United States, and collapsed the price, the great panic of 1819 set in.

The following is from ‘1816 – America Rising’, by C. Edward Skeen – Chapter 4, ‘A Tariff and a Bank’:

“The British were well aware of the growth of American manufacturing in the post-war period, and with large inventories and a desire to re-establish their former levels of export of manufactured goods to the United States, began emptying their warehouses and undercutting the prices of American manufacturers. Cheaper British goods, particularly textiles, led to demands by industrialists for congressional action to restore a balance of competition. On the other hand, Southern farmers, buoyed by rising cotton prices, which reached 29 cents a pound in 1816, were expanding cotton farming and were content to continue the status quo. New England shipping interests engaged in the carrying trade were also loath to engage in restrictive systems or commercial warfare.”

Carey writes about the outcome of the ‘destructive tariff’. [taken from the Autobiography of Mathew Carey, that originally appeared in the New England Magazine, from Letter XXIV]:

“At length peace came ‘with healing on its wings’. To all classes except to the manufacturers, who were devoted to destruction by an infuriate spirit of hostility which was grounded on a most calumnious charge of extortion, because the prices of various articles of domestic production, more especially woolens, had been raised during the war. To render this envenomed and delusive cry of extortion more criminal, and (if it had nor proved so fatal) more ludicrous, it is to be remarked, that in the year 1816, in which the welkin rang with it, and in which a destructive tariff was enacted, the great staples of the country, produced by the very men who rang the changes on the extortion of the Manufacturers, rose enormously …

The manufacturers had been among the most zealous and ardent supporters of the war. There was scarcely a man among them that was disaffected to the cause of their country. But had they all been traitors, as black and fiendish as Arnold, a fouler spirit could not have prevailed against them, than was manifested by the Congress of 1815-16. They were the devoted victims of the grossest prejudices. Of those who felt this spirit most virulently, Gov. Wright of Maryland and John Randolph of Roanoke, were the most conspicuous … John Randolph with his usual vehemence gave a solemn pledge, that he would never wear, nor allow any of his people to wear, a single article of American Manufacture.

The illiberal spirit had ample room for display in the discussions of the details of the tariff … the duties were reduced on no less than forty-four articles, from 2 to 33 per cent. Thus, in an evil hour, were blasted the hopes, the happiness, the fortunes of thousands of individuals who, seduced by the delusive expectations held out by the Government had devoted their fortunes, and their time, and their talents, to furnish their country with the necessaries and comforts of life, at a period when she was debarred of supplies of many of them from the old world. And thus were blasted sources of national wealth and prosperity ….

It was vainly expected that the generality of our citizens would profit by these reduced duties; that they would thereby be able to procure foreign manufactures on easy terms, and secure themselves from the extortion of the manufacturers. Never was there a much more miserable error, and never was illiberality and oppression much more severely or justly punished. Great numbers of the Manufacturers and their operatives migrated into the country; the former to commence farming. And the operatives to become field laborers.

Desolation spread over the face of the land in the manufacturing and farming portion of the nation. The cotton planters, who almost to a man had voted against protection, were soon involved in the general distress. The depression of farming, by the conversion of so many manufacturers into farmers, thus rendering those rivals who had been customers, induced numbers of farmers who had migrated to the southwestern States, to commence cotton planting, and so far glutted the market … thus increasing the quantity nearly 50 per cent. The consequence was a most ruinous reduction of price, which produced nearly as much distress in the cotton-growing States as had taken place among the manufacturers and farmers, and ruined a large portion of the merchants engaged in cotton shipping. Thus the poisoned chalice which the cotton planters had drugged for the ill-fated manufacturers, was, by a just dispensation, returned to their own lips.”

Such was the desperate state of the country, and the inadequate understanding of a large number of the members of Congress and of the population, that Carey now again began organizing and writing in defence of the nation, and his offensive against free-trade, proceeding ‘to investigate the real causes of the distress’. And here we learn of his growing opposition to Adam Smith!

The following is from the Autobiography of Mathew Carey, that originally appeared in the New England Magazine, from Letter XXV:

“At the crisis of the affairs of the country … there was a small society formed in Philadelphia, entitled the Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of National Industry. There were only ten members – James Ronaldson, Wm. Young, Thomas Hulme, Samuel Jackson, Thomas Gilpin*, John Melish, James Cutbush, Joseph Nancrede, Joseph Siddall, and M. Carey. The object of the society was to advocate the protection of national industry generally, but more particularly of manufactures, as perishing for want of protection.”

* [Note: Thomas Gilpin, with his brother Joshua, started the first paper-making factory in the United States, and his nephew was William Gilpin, who became the first governor of Colorado and the author of ‘The Cosmopolitan Railway’ (1890). For more information on the Gilpin family, please read ‘William Gilpin and the Original World Landbridge Project’ by Matthew Ehret.]

“It is due to myself to state, that in the modification of the Tariff, I had no personal interest whatever, to the amount of a dollar … I nevertheless entered on the defense of the protecting system, with as much zeal and ardour as if my life and fortune were at stake …

I had read but little on the subject, and had no recollection of having ever previously written a line on it. I had once taken up Smith’s Wealth of Nations, with an intention of studying it; but found it so dry, so abstruse, and so completely filled with what I regarded as extraneous matter, that I laid it down without an intention of resuming it. And when the society was formed, I had no idea of writing essays on a subject which I had so little studied. I undertook to collect a few maxims on political economy to form a manual for the guidance of our statesmen in the labyrinth in which that science is involved. And as Adam Smith was the most popular writer on the subject, I began with him. To my great surprise I found a gross contradiction on a most vital point, which nullified the great staple of his system …

These positions, absurd, futile, and untenable as they are, form the basis of the Wealth of Nations. To a person wholly unbiassed by prejudice, it must be a matter of astonishment, how a work, resting on such a sandy and miserable foundation, could have obtained, and still more, have so long preserved, its celebrity. The monstrous absurdity of these doctrines, and the facility with which they might be refuted, induce me to enter the lists against this Goliath, with the sling and stone of truth …”

and from Letter XXVI:

“When I commenced writing on this all-important topic, I did not intend to go beyond the two first essays … but these two were received with such approbation, and were so generally copied into the newspapers north of the Potomac, that I was encouraged to proceed, and wrote nine more, which were as favourably received and had as general a circulation, as the first two. They were originally published by the Society in pamphlet form … Of the essays, two, Nos. 12 & 13, were written by Dr. Samuel Jackson.”

And so, Carey began his attack on the writings of Adam Smith, the promotion of the ideas of Alexander Hamilton, and the education of the population in what would become known world-wide, as the ‘American System’.

The following is from ‘Addresses of the Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of National Industry’, from the Preface:

“The advocates of the system of Adam Smith ought to be satisfied with the fatal experiment we have made of it. It is true, the demands of the treasury have not allowed us to proceed its full length, and to discard import duties altogether. But if our manufactures are paralized, our manufacturers ruined, and our country almost wholly drained of its metallic medium, to pay for foreign merchandize, notwithstanding the duties imposed for the purpose of revenue, it is perfectly reasonable to conclude, that the destruction would have been more rapid and complete, had those duties not existed …

We flatter ourselves that the most decided advocate of the doctor’s system will admit, on calm reflection, that these maxims are utterly destitute of even the shadow of foundation.

We urge this point on the most sober and serious reflection of our fellow-citizens. It is a vital one, on which the destinies of this nation depend. The freedom of commerce, wholly unrestrained by protecting duties and prohibitions, is the keystone of the so much extolled system of the doctor, which, though discarded, as we have stated, in almost every country in Europe, has, among our most enlightened citizens, numbers of ardent, zealous, and enthusiastic admirers. We have essayed it as far as our debt and the support of our government would permit. We have discarded prohibitions; and on the most important manufactured articles, wholly prohibited in some countries, and burdened with heavy prohibitory duties in others, our duties are comparatively low, so as to afford no effectual protection to the domestic manufacturer. The fatal result is before the world – and in every part of the union is strikingly perceptible …

This is the basis on which Adam Smith’s system rests, and being thus proved radically and incurably unsound, the whole fabric must crumble to ruins.

There is one point of view in which if this subject be considered, the egregious errors of our system will be manifest beyond contradiction. The policy we have pursued renders us dependent for our prosperity on the miseries and misfortunes of our fellow-creatures! Wars and famines in Europe are the keystone on which we erect the edifice of our good fortune! The greater the extent of war, and the more dreadful the ravages of famine, in that quarter, the more prosperous we become! Peace and abundant crops there undermine our welfare! The misery of Europe ensures our prosperity – its happiness promotes our decay and prostration!! What an appalling idea! Who can reflect without regret on a system built upon such a wretched foundation!

What a contrast between this system and the one laid down with such ability by Alexander Hamilton, which we advocate. Light and darkness are not more opposite to each other. His admirable system would render our prosperity and happiness dependent wholly on ourselves. We should have no cause to wish for the misery of our fellow men, in order to save us from the distress and embarrassment which at present pervades the nation. Our wants from Europe would, by the adoption of it, be circumscribed within narrower limits, and our surplus raw materials be amply adequate to procure the necessary supplies.

Submitting these important subjects to an enlightened community, and hoping they will experience a calm and unbiassed consideration, we ardently pray for such a result as may tend to promote and perpetuate the honour, the happiness, and the real independence of our common country.”

I hoped to have shown, in Mathew Carey’s own words, that contrary to some misleading sources, Carey didn’t change – instead, he changed others. From his youth, fighting for the independence of Ireland from the British Empire, to his adult life in the United States, fighting for America’s independence from the same British Empire, he never changed his ideal – he simply got better at it.

The effect of Carey’s work and writings, to educate the American population in understanding the basics of the ‘American System’, can best be summed up in the announcement of a young man, of his intention to run for public office, for a seat in the state legislature:

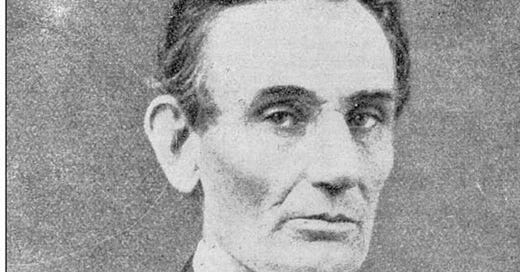

Abraham Lincoln

“I presume you all know who I am. I am humble Abraham Lincoln. I have been solicited by many friends to become a candidate for the Legislature. My politics are short and sweet, like an old woman’s dance. I’m in favor of a national bank. I’m in favor of the internal improvement system and a high protective tariff. These are my sentiments and political principles.”

And today’s new emerging multipolar and independent world, to succeed, will need to learn the valuable lessons taught to us by Mathew Carey.