Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution

an RTF presentation by Gerald Therrien

This is a presentation that I gave for the Rising Tide Foundation, on Toussaint Louverture, (who probably did more than anyone to end slavery) on the Haitian Revolution, and also, on its effect on Canada and on the United States.

The presentation is about two hours. You may watch the video, and/or you may read the full transcript. For this class, I didn’t have a written text that I read from, but only some rough notes that I used to follow along with the slides. So I’ve tried to type the full transcript (with my rants and all), [with only a bit of editing where it was needed].

A fuller picture of this whole story will be found in my book ‘To Shining Sea – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana, and the Fight for a Continental Republic, 1797–1804’, Volume 4 of The Unveiling of Canadian History, that hopefully, may appear in print in the near future.

Toussaint Louverture, the Haitian Revolution, and the effect on Canada and the United States

by Gerald Therrien

To look at Haiti, we have to go back to Columbus.

The first attempted colonies in the New World by Columbus were on the island of Haiti. He called it - La Isla Espanol, and they latinized it to Hispaniola.

When Columbus made his voyages, the enslavement of native people was not allowed. But Spain’s feudal labour system, that was imposed on the natives, and later, the spread of disease, especially smallpox, disastrously reduced the native population. And you can’t blame Columbus for this. He worked for the king and queen of Spain – they made policy.

But, since slavery was legal in Spain, slaves in Spain could be brought to the Spanish colony as slaves. They couldn’t be brought directly from Africa, but if you owned slaves in Spain, you could bring them to Haiti. And you can’t blame Columbus for that, because that’s the law of Spain.

In 1518, the Spanish Empire under the Hapsburg king Charles I, who became the Holy Roman Emperor, allowed enslaved Africans to be directly imported to the Spanish colonies, to work in the mines and on the sugar plantations, because the native population was dying off. And this is when the African slave trade really began to expand. You can’t blame that on Columbus either, because he died in 1506, so this is 12 years after his death.

I just say all this because there’s these people running around trying to pull down statues of Columbus, and I think they’re massively mis-informed, especially that mayor in Chicago [i.e. Lori Lightfoot]. And the best thing to do is to read a book on the Life of Columbus by Washington Irving, and you really get a sense of this guy. And don’t read this book by Howard Zinn, he’s a complete fraudster, and that’s where a lot of this anti-Columbus stuff comes from.

Now, I just want to look at what the world was like when the revolution in Haiti started in 1791.

Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1791

The western end of the island of Haiti (by then the Spanish were calling it Santo Domingo) began to be colonized by France in 1664, and the French called it Saint-Domingue. Slavery was allowed in the French colonies by the ‘Traite des Noirs’, which was issued by Louis XIII in 1642. That’s when the French started getting into the slave trade, around then. The British were a little before, they had the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company doing it [around the 1620s].

In 1791, the French colonies in the West Indies were the islands of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Tobago, Saint Lucia, and Saint-Domingue. But the most important colony economically was, by far, Saint-Domingue, with its 398 cotton & indigo plantations, its 1,962 coffee plantations, and its 655 sugar plantations, which contributed two-thirds of France’s tropical produce and one-third of its foreign trade. So, this was like their goose that laid the golden egg – all on slave labor.

The majority of the plantation owners were called ‘grands-blancs’ – big-whites, and they lived on their plantations. A minority of them [absentee landlords] lived in France, but the majority lived there in Saint-Domingue. There was a middle class of merchants and shopkeepers, and lower class of plantation overseers, artisans and mechanics, that were called ‘petits-blancs’ – the little-whites. Together the big-whites and the little-whites made up about 35,000 of the colony’s inhabitants.

There was also the mulattoes (which is a horrible name) and free blacks, together were called ‘gens de couleur’. And they owned about one-third of the plantations and about one-fourth of the slaves in the colony. But they had to face social and racial discrimination, and they were not allowed to hold any public office, any public trust, or employment, and they made up about 25,000 of the inhabitants – a little less than the big-whites and the little-whites). But the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants in the colony were the almost half a million enslaved Africans, who laboured on the plantations. Over 2% of the slaves died each year (some people say it was 5%). You basically had to import between 10,000 and 20,000 slaves from Africa every year just to replace the ones that you worked to death, let alone to open up new plantations. So that was life in Saint-Domingue in 1791.

United States in 1791

By 1791, except for Georgia, which came a little later, all of the American states and territories had either abolished slavery or had banned the importation of slaves. The United States of America was the leading nation in the entire world, in the cause of ending slavery and the slave trade. I just want to repeat that because no one seems to admit this – but the United States of America was the leading nation in the world in the cause of ending slavery and the slave trade, in 1791. Of course, people say … ahhh, what happened? between then and the civil war, but I’m not going to go there. We have to wait for Anton Chaitkin’s book to come out, and you’ll see what happens. [please check out Anton Chaitkin’s Substack here.

Slavery was abolished in Rhode Island in 1774, in Vermont in 1777, Pennsylvania 1780, Massachusetts 1781, New Hampshire 1783, Connecticut 1784, and the Northwest Territory 1787. The Northwest Territory [called the Ohio country] was everything north of the Ohio river and east of the Mississippi. It used to be part of Virginia territory, but they donated it to the Union, and agreed, along with everyone, that there would be no slavery allowed in the Northwest territory, so that when any states are formed out of this territory later, there would be no slavery there.

Slave importation was banned in Delaware 1776, Virginia 1778, Maryland 1783, New Jersey 1786, North Carolina 1786, South Carolina 1787, New York 1788, and Georgia in 1793. So, by 1793, every state and territory had done one or the other. Slave importation is a mixed thing. Some people who were against slavery, who couldn’t get slavery banned, were in favor of at least banning the importation of it. There was other people, particularly in Virginia, that had a surplus of slaves, so they wanted to ban the importation of slaves, so that they would be able to sell their slaves to the other states, at a higher price. So the importation ban is kind of a mixed thing. So now let’s look at Canada in 1791.

Canada in 1791

Canada, of course, was affected by the Tory refugees and militia troops that were sent to Canada, between 1776 and 1783 when the American Revolution ends. Here [in Canada] we’re taught to say they were loyalists, but Americans get to call them tories.

In Nova Scotia: 30,000 tories and troops, which included 1,200 slaves and 3,000 free blacks, were sent to Nova Scotia. But two-thirds of all the free blacks were denied land grants or food, which they had been promised, and they were forced into being an indentured servant and they were exploited as cheap labor. In January of 1792, almost 1200 of these free blacks elected to leave Nova Scotia and relocate to Sierra Leone, in Africa.

In Upper Canada (that’s Ontario): 10,000 tories and troops, including 500 slaves, came to Ontario. Some of them simply relocated from Nova Scotia and Lower Canada, because they were giving out free land in Upper Canada.

In Lower Canada (in Quebec): 6,000 tories and troops, including 130 slaves, went to Quebec. Most of them began arriving as early as 1776 from northern New York State. When the revolution broke out and the fighting started, a lot of the [tory] settlers in the north had to flee from the revolutionary troops and they just went right up Lake Champlain and the Richelieu river and settled where the British forts were along there.

Since the census of 1784 in Lower Canada listed 304 slaves total, and if you subtract the 130 slaves that the tories brought, it’s estimated, that before the tories arrived, there were 174 slaves in all of Lower Canada (Quebec) – African and mostly Indigenous slaves. About two-thirds of all the slaves in Canada were natives (Indigenous people). A lot of the French fur traders would go out west to trade for furs, and sometimes they would trade for slaves and bring them back. The African slaves were harder and more expensive to get. It’s horrible to say, but most of the African slaves were to prove that you had money, and they were servants in your house. No slave ship ever came to Quebec, so if you wanted an African slave, you’d have to go to the slave markets in the States, or somewhere else.

So, there was 174 slaves in all of Quebec before the tories came. Thomas Jefferson owned more slaves than all of French Canada – he had 200 of them. So it kind of puts it in perspective. And, if you were a slave in Canada and you escaped, you would, of course, flee to the United States, where slavery had been abolished. What we think of as the Underground Railroad actually started the other way.

In 1793, during the first elected assemblies in both Canadas, (they finally got assemblies), in January, a Lower Canada [Quebec] bill to stop the importation of slaves was introduced but not passed. In Upper Canada [Ontario] in June, a bill to stop the importation of slaves was passed. So on the anti-slavery meter, we’re [Canada] tied with Georgia!

When the Legislative Council in Canada was holding hearings in 1787, because the people living in Quebec wanted to have a legislative assembly (finally) and they were presenting petitions to the Legislative Council, there was also this interesting address they inserted:

A Prohibition to the bringing of Slaves into the Country.

‘Slavery being alike contrary to the principles of humanity & to the spirit of the British constitution.

This committee recommends that means be adopted to prevent the bringing of slaves into the province in future, but as to the few Negro or Indian slaves who are already in servitude, they conceive that they ought not in justice or policy to be emancipated…’

(So they didn’t really want to free the slaves, but they did want to stop the importation.)

‘to many families there are of them valuable as property, and servants, and we have frequently seen instances of slaves being manumitted, soon becoming idle and disorderly, and finally a burthen to the public...’

(If there’s only 174 slaves in all of Quebec, how many of these are actually freed a year – maybe one! And this one guy is becoming idle and disorderly, and a burden to the public? I think this last part got written by someone who actually owned slaves and was just sticking that in there to give his excuse.)

‘We would further recommend that after years, all infants who shall be born of parents who are slaves be declared free.’

This is what you call ‘gradual emancipation’, and even though it was introduced in Montreal in 1787, it’s almost word for word, the bill that was passed in Ontario in 1793, and the one they tried to pass in Lower Canada [Quebec] in January that failed.

Britain in 1791

The abolition movement in England was started by a man named Granville Sharp – a fascinating guy (I’d like to talk more about him but I can’t now). He was a good friend and collaborator of Dr. Benjamin Franklin, while he was over there. You could say that Dr. Franklin helped start the abolitionist movement. For the British, even after Yorktown at the end of the revolutionary war, they were still trying to mobilize African slave troops, urging slaves to flee the plantations and come over behind the British lines. But it wasn’t because they were anti-slavery, they were using this as part of economic warfare against the United States. After the end of the war in 1783, when the British finally pulled out of the United States, they had three ports they were still in. In Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia, many of the former slaves were sent to Florida or Jamaica, and many of these were captured and re-sold back into slavery. Many of the former slaves at New York, who were granted their freedom for wartime services - they actually fought in black regiments for the British army, these were the ones who were shipped to Nova Scotia.

In 1791 (due to the work of Granville Sharp and his collaborators), the British House of Commons introduced a bill to abolish the importation of slaves to the colonies – not into England, but to the colonies. But it was voted down almost 2 to 1. So, Britain is actually behind Georgia on the anti-slavery meter.

In 1793 (Britain at that time was at war with France), the British government passed the Seditious Meetings Act & the Treasonable and Seditious Practices Act that targeted abolitionists and also other reformers (people who were trying to get the right to vote) which paralyzed and suppressed any of their organizing, petitioning or meetings. So the abolition movement was shut down at that point.

And also that year, 1793, the British invaded Saint-Domingue, to try to put down the slave revolt, because they wanted to stop the rebellion from spreading to their slave plantations in Jamaica and their other colonies. It shows you that slavery in England was viewed differently than slavery in the British colonies.

And to just show this point, in 1793 the Lt. Governor of Upper Canada, [John Graves] Simcoe, signed into law the bill against slave importation into Upper Canada [Ontario]. In 1797, he was sent as Commander-in-chief to fight Toussaint Louverture and the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue.

When I was first doing work on this, maybe 10-15 years ago, I sent some of this to Pierre Beaudry, to say - isn’t this king of contradictory. Is Simcoe for slavery or is he against it? And he sent back an e-mail saying – No, it’s not contradictory. You have to ‘pay attention to the intention’. Why were they doing this? And then you start figuring the whole thing out.)

[please check out Pierre Beaudry’s website here]

(There’s the island of Hispaniola. On the right, this is the Spanish part, Santo Domingo. This [on the left] is the French part, called Saint-Domingue.)

1791

On August 22nd 1791, the slave rebellion started, near the capital, Cap Francais, in the North Province. A hundred thousand slaves revolted in the North Province of Saint-Domingue, led by a man named ‘Boukman’. It’s hard to find anything out about this guy, but Boukman had been a slave in Jamaica and had been called ‘Book Man’ because he had taught himself to read and write. But, after he’d tried to teach other slaves how to read and write, he was sold by his British owner to a French plantation owner in Saint-Domingue, and his name, instead of ‘Bookman’, became ‘Boukman’ (a French accent, I guess). At one of their regular night meetings, on August 14th, the assembled slaves swore an oath to break their chains or die. A week later, the revolt began. In the South Province and West Province, the ‘gens de couleur’ revolted and they were joined by the slaves there too.

And I just asked myself, ‘How was this organized?’ – I mean, a hundred thousand people revolted at once!!! ‘How do you do this?’ And there’s nothing about it. They don’t write about how this was done. Some guy writes about the socio-economic blah-blah-blah, and some other guy writes about the anthropological blah-blah-blah. And someone says ‘Oh, I read your blah-blah-blah. It was very good. Now here’s your PhD – you’re a doctor of blah-blah-blah’. And this is the garbage you have to sift through. But my understanding is, because if you’ve ever tried to organize other people to come to a meeting, or do petitioning, or hand out literature or something, it’s a lot of work, and you get a few people. But A Hundred Thousand!!! This is what they don’t want to admit – he must have had his network of organizers and they had theirs, and somehow they had these meetings, and by the next day or two, it had spread to every plantation in the North. And all I can think is this guy Boukman must have been the greatest organizer of all time – a hundred thousand people! And they had no weapons – you grabbed a stick or whatever farm implement you could steal. But it wasn’t just because ‘oh I’m a slave, I’m not going to live long here anyway, what have I got to lose’. No, they actually had a higher purpose, they had a higher intention on it.

1792

When the slave revolt broke out, in France the National Legislative Assembly, which was the new government in France after the adoption of the constitution, what they did was grant full citizenship to the ‘gens de couleur’. There was an anti-slavery society in France at the time, ‘Societe des Amis des Noirs’ that Lafayette was part of, and had been organizing. Now, you could say, ‘well, I guess this was the best they could get’, but remember by August of that year, Lafayette had to flee the country or they would have chopped his head off, along with the other leadership. So really, they granted citizenship to the ‘gens de couleur’ simply to gain their support against the slaves, figuring if the ‘gens de couleur’, instead of allying with the slaves and fighting the ‘big whites’ [grand-blancs] and ‘little-whites’ [petit-blancs], would ally with them against the slaves, we might be able to turn this thing around. So the intention of the French government was not good.

They also sent three Peace Commissioners and 7,000 troops to Saint-Domingue. So that shows you what their intention really was. When they got there, the commissioners decreed the protection of slavery, and the recognition of full citizenship for all the ‘gens de couleur’. The Insurgents were badly beaten by the French troops, and they were driven inland and into the mountains, where they tried to do guerilla warfare, but they weren’t doing too good.

1793

In 1793, France declared war on Britain and Spain. So Spain’s thinking – now that they’re at war with France, they’re going to try to regain the western end of the island and then have the whole thing. So they began supplying the Insurgents (that’s what they called the revolting slaves – they were called the Insurgents). They supplied them with arms and encouragement. And 4,000 Spanish troops, along with their Insurgent allies, launched an invasion of the North Province. Now the British, since that they were now at war with France, decided they were going to seize the French West Indien colonies. They seized Tobago, Martinique, Saint Lucia and Guadeloupe. Then the British navy launched an invasion of Saint-Domingue, to capture France’s most important colony, but also to stop the slave revolt from spreading to Britain’s most important colony, Jamaica.

In August of that year, with the Spanish army and their Insurgents attacking in the North, and with the British preparing to invade the western and southern ports, one of the [French] Peace Commissioners – Sonthonax, decreed the abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue. But it’s not what the slaves thought it meant. He simply was hoping that the ex-slaves, the Insurgents, would simply now return to the plantations, where they would work, not as slaves, but as paid labor – but at least this way the French wouldn’t have to fight them, and could only fight the Spanish and the British.

1794

With the Spanish controlling most of the North province, and the British controlling most of the West and South Provinces, a French defeat was only a matter of time. So early 1794, the French National Convention (that’s the new government of France now with a new constitution) declared the abolition of slavery in all of the French colonies. They really didn’t have any French colonies – the British had seized all of them, and they sort of had Saint-Domingue but they were about to lose it to the Spanish and the British. So really, they declared the abolition of slavery in the colonies as a way to start the slave revolt in these other colonies that the British had seized and maybe it would spread to Jamaica. They were just trying to create chaos. The French National Convention declared the abolition of slavery. Word of this got back to Saint-Domingue. Upon hearing of the French government’s declaration, Toussaint Louverture, who was one of the Insurgent leaders allied with the Spanish, decided he was going to switch sides, and he was going to fight alongside the French against both the Spanish and the British. And this was a decision that would change the course of history.

1795

During the next year, the Spanish were driven back eastward, into Spanish Santo Domingo. The British were driven back to the coast, and they only held a few of the ports. In Europe, Spain had withdrawn from the coalition against France, and they withdrew from the fighting in Saint-Domingue, and they ceded all of Santo Domingo to France. They gave them the whole eastern part of the island. Although the Spanish stayed there to administer it, it was officially part of France now. Most of the Insurgents who had fought with the Spanish, would all join Toussaint’s army, and he soon controlled most of the North Province and the West Province. Because of his efforts, National Convention promoted Toussaint to Brigadier-General in the French Army.

1796

The next year, with the Spanish out of the fighting, and the British only having a few ports, they [the British] had to make a decision. So they decided to launch (they called it) ‘the great push’ – they sent 30,000 men and 200 ships to try to conquer Saint-Domingue. They’d come with their navy, and just bomb all of the ports, and General Toussaint sort of had to use guerrilla tactics – pull back to the interior, try to hit them and pull back, so that his army wouldn’t be destroyed. But the British also were doing a lot of subterfuge. They secretly encouraged the commander at Le Cap Francais, the capital of North Province, they convinced him to capture the Governor [Laveaux] and to take over. But General Toussaint sent 10,000 troops to rescue the Governor, and the Governor made General Toussaint the Lieutenant-Governor of Saint-Domingue. So he’s a Brigadier General and he’s the Lieutenant Governor of Saint-Domingue.

1797

The fighting continued. In 1797, [British] General John Graves Simcoe (the former Lt-Governor of Upper Canada) became the Commander-in-chief. He arrived in February, but by August he returned to Britain because, he said, the government failed to provide him enough troops and supplies that he felt were necessary to win. Also at this time, malaria and yellow fever were attacking the troops as well. They were dying of disease. For his success in fighting the British, the French Directory (the new government in France) made General Toussaint the Commander in Chief of all the French forces in Saint-Domingue. They had great respect for his leadership.

During the 5 years of the British invasion of Saint-Domingue, it would cost them more than £7 million as well as over 20,000 casualties. And the British army had purchased over 13,000 slaves, to raise African slave regiments to do the fighting for them, which made them the largest single buyer of slaves in the Caribbean. (So much for General Simcoe’s anti-slavery sentiments.)

(this is a better map [of Saint-Domingue] and you can see the North Province, West Province and the South Province)

1798

General Toussaint began to negotiate an agreement with the next British general, General Maitland, to begin the British withdrawal from most of Saint-Domingue – that Britain would promise not to invade Saint-Domingue again, if General Toussaint promised never to attack Jamaica. And he agreed to that. Maitland also proposed that if Saint-Domingue would declare independence from France, they would receive the protection of the British navy from the French. General Toussaint rejected this because he did not fully trust Saint-Domingue’s future to the British Empire (after fighting them for five years).

At the same time, the Directory sent an agent, Hedouville, who arrived with the Directory’s secret plan for an invasion of Jamaica, and later of the southern United States! This would help to spread the slave revolt, but it would also get Toussaint out of the way, and Hedouville felt then he could re-establish French control over the island. General Toussaint rejected this invasion of Jamaica because he knew such a plan would destroy his army, and ‘the old system might be restored in Saint-Domingue and slavery re-established’. He realized it was just like George Washington – you could not lose your army! You could lose battles all you want, but you couldn’t lose the army – at that point, it was all over. That’s why you fought guerrilla warfare, so you didn’t have a head-on confrontation and lose.

1799

General Toussaint, not trusting either the French or the British, decided that he could trust the Americans! And he sent a businessman from Le Cap [Joseph Bunel], along with the American Consul, Jacob Mayer, to Philadelphia, where they met with Secretary of State, Timothy Pickering, they met with some congressmen, and, secretly, they met with President Adams at dinner. And they proposed that trade with America would be permitted, and American ships would be protected in all of Saint-Domingue’s ports. At this time, the United States and France were basically at war – they call it the Quasi-War. France was trying to get the United States to openly ally with them in the war against Britain, and the United States wished to remain neutral to all this nonsense going on in Europe. The French said, well ok, then you’re not honoring the treaty, so we don’t have to honor neutral ships. So they began seizing any American ship they found in the Caribbean. There was something like over 400 ships that would be seized. After their meetings with President Adams, and Pickering, and the congressmen, in the United States Congress a bill was introduced and debated to continue the suspension of trade with France, but it included a new clause that would allow US trade with Saint-Domingue – this was called ‘Toussaint’s Clause’. And the bill was passed. At the same time, Timothy Pickering, the Secretary of State, wrote a letter to Alexander Hamilton, informing him that a bill was being passed and we would be having trade with Saint-Domingue, and he asked Hamilton for a plan for Saint-Domingue to administer the government.

(To avoid all the over-complication of the issue of independence and everything), Hamilton alone seems to have understood the reality of Saint-Domingue, that there was very little in the way of democratic institutions on which to base a representative government, and that law and order was maintained by the army. Hamilton also understood General Toussaint, that he had not proposed independence and he wished to remain loyal to France. Because, remember how many nations on earth had abolished slavery? To his knowledge only one, France. General Toussaint was not committed to independence, he was determined to defend the freedom of his fellow former slaves, at all costs. He was fighting for freedom, not for independence. He would only fight for independence if it became absolutely necessary, in order to defend their freedom. And Hamilton understood that, and none of these other people do, and they’re all babbling about ‘oh, they should declare independence, and we can get more trade with them’. But no, that wasn’t going to happen. That was not General Toussaint’s intention.

After this, Secretary of State Pickering sent an advance shipment of pay, clothing and provisions for Toussaint’s troops, for a credit. That was very nice of him, to show that this was going to be friendly relations between United States and Saint-Domingue. Also sent was Dr. Edward Stevens, who was appointed the Consul General and when he went, he took Hamilton’s plan with him to Saint-Domingue, to give to General Toussaint. Dr. Stevens (it turns out) was Hamilton’s oldest and closest friend. They had grown up together as boys in the Caribbean and met later in the United States. Also in 1793, Hamilton and his wife had caught yellow fever in Philadelphia, and Stevens basically had saved their lives. (There were some wacko theories of how to combat it – they’d put on leeches on you, or they’d bleed you, or give you these powerful purgatives.) Stevens, because he had grown up in the Caribbean, knew yellow fever, and he had an idea of how you could fight it, which he did. I think he used ice baths with Hamilton and his wife and they recovered. So he saved Hamilton’s life.

While he was in Saint-Domingue, he would also uncover a plot by the agent of the [French] Directory to invade the southern US and he informed General Toussaint of this, and this plot was squashed by Toussaint. At this point, General Toussaint and Dr. Stevens negotiated a trade agreement between United States and Saint-Domingue, and they then negotiated a secret treaty with Maitland, for Britain to join this. Although Toussaint didn’t trust Britain, but because of the British naval superiority, he knew any agreement with the United States would be useless, without an agreement from the British navy as well. So they got Britain to become part of this treaty too. Then President Adams would issue a proclamation to re-open trade with Saint-Domingue, and he sent Commodore Talbot and the USS Constitution, which was one of the 6 frigates that were built for the new US Navy. So one of their only 6 ships, he sent, with a few others as a fleet, to be stationed at Le Cap in Saint-Domingue. So we’ve got the US Navy down there.

1800

Immediately after this secret treaty, General Rigaud, who was the commander of the South Province, (Toussaint was the commander of the North and West Provinces) with the connivance of Hedouville, who was the French agent for the Directory, launched an attack against General Toussaint, and started a revolt of the ‘gens de couleur’ in the North and West Provinces against Toussaint’s army. It was a like a civil war at that point. After Toussaint was finally able to suppress the uprising in the north, he then began to move to launch an offensive in the South, and he reached an agreement with Dr. Stevens to allow a squadron of [Toussaint’s] ships to sail to Jacmel, where he could blockade the port but also to re-supply Toussaint’s troops.

But, the British, claiming that they feared that squadron was destined for Jamaica, seized the ships. So now Toussaint doesn’t have a navy, because that was all he had. So then, Commodore Talbot and Stevens got together and sent Captain Perry and the USS General Greene, one of the American vessels, south to Jacmel – both to stop Rigaud’s gunboats that were actually attacking American merchant ships in the area in the southern ports, but also to stop the clandestine trade that was going on between Jacmel and the British colony of St. Thomas – that’s how the British had been secretly supplying Rigaud. Also this would assist General Toussaint in the capture of Jacmel. With Captain Perry firing on Rigaud’s forts at Jacmel, General Toussaint was able to storm them, and they captured that. Soon the fighting in the south was over, and Rigaud fled to France, to cry in Bonaparte’s ear about how bad a person Toussaint is. The first thing General Toussaint does, is issue a proclamation of clemency to all of the inhabitants of the South. He’s not going to take revenge. There’s no punishment for that – just clemency.

After that, in France, a coup has installed Napoleon Bonaparte as the First Consul in another new government, and General Toussaint receives a decree from Bonaparte that says:

“French colonies will be ruled by special laws. This disposition derives from the nature of things and the differences in climate…”

(I laugh whenever I read it, because it sounds like he’s getting advice from David Suzuki, the Nature of Things, on climate change.)

“The inhabitants of French colonies located in America, Asia, and Africa cannot be governed by the same laws. The differences in habits, in mores, in interests; the diversity of soil, crops, and goods produced, demands diverse modifications…”

What is Bonaparte hinting at? What’s his intention? Because this ‘David Suzuki’ speech does not make sense at all. At that point Toussaint knows he’s in for trouble, so he informs the Spanish Governor of Santo Domingo that he was taking control for France. Remember that Spain had ceded it to France, back in 1795 (5 years ago) and it’s still being administered by the Spanish. General Toussaint is the Commander-in-chief of all the French forces there, and he’s the Lt.-Governor, so he has the authority to do that. Also there’s a reason why he did it. What was happening is, that the Spanish were sneaking into the French part of Saint-Domingue onto the plantations, and capturing some of the freed men and bringing them back to Santo Domingo where they were sold back into slavery, for Cuba! That’s really why he was doing it, not all this nonsense about he wanted to be dictator over everything. No. His intention from day one was to end slavery, and now he had a chance to do it on the whole island.

1801

The first thing he did was proclaim amnesty to all of the Spanish colonists. He abolished slavery throughout the entire united island, and he called an election. Ten men were to be chosen for a Central Assembly, two from each of the five departments – the three in the French part (the North, West, and South provinces), and the two provinces of the former Spanish part [Engana and Samana departments]. And this assembly was to draft a constitution – a new constitution for Saint-Domingue, using Hamilton’s draft as a model, and also using the French ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’. (that’s what he was going to use as his model).

On July 3rd 1801 the new constitution was proclaimed into law.

Here is Hamilton’s letter that he wrote February 21st 1799, when Secretary of State Pickering asked him, and he gave it to Dr. Stevens to bring and give to General Toussaint. Hamilton says:

“No regular system of Liberty will at present suit St. Domingo. The Government, if independent, must be military – partaking of the feudal system. A hereditary Chief would be best but this I fear is impracticable. Let there be then – A single Executive to hold his place for life…”

(He was thinking of General Toussaint.)

“The person to succeed on a vacancy to be either the Officer next in command in the Island at the time of the death of the predecessor, or the person who by plurality of voices of the Commandants of Regiments shall be designated within a certain time. In the meantime, the principal military officers to administer...”

(He was saying you have a council of the commanders of the regiments who will decide who is the next chief. And also whether he’s going to remain there.)

“All the males within certain ages to be arranged in Military Corps and to be compellable to military service. This may be connected with the Tenure of Lands.

Let the supreme Judiciary authority be vested in twelve Judges to be chosen for life by the Generals or Chief Military Officers…”

[the circle of officers]

“The powers of war & treaty to be in the Executive. The Executive to be obliged to have three ministers – of finance, war & foreign affairs – whom he shall nominate to the Generals for their approbation or rejection.

The Colonels & Generals when once appointed to hold their offices during good behaviour removeable only by conviction of an infamous crime in due course of law or the sentence of a court martial cashiering them.

Duties of import & export, taxes on lands & buildings to constitute the chief branches of revenue.

These thoughts are very crude but perhaps they may afford some hints.”

Hamilton was saying it should be a military-type government because he [Toussaint] would need that to keep the country together and defend their freedom. For Hamilton this was nothing new. Hamilton was attacked as a monarchist, wanting to have a hereditary monarch in the United States (blah-blah-blah).

This is what Hamilton presented as his Plan of Government, at the Constitutional Convention, back in 1787.

“1. The Supreme Legislative Power of the United States of America to be vested in two distinct bodies of men – the one to be called the Assembly and the other, the Senate; who together shall form the Legislature of the United States, with power to pass all laws whatsoever, subject to the negative hereafter mentioned.

2. The Assembly to consist of persons elected by the People to serve for three years.

3. The Senate to consist of persons elected to serve during good behaviour…”

(He wanted the senate to serve for life, because it would take away from immediate changes of opinion among the electorate.)

“Their election to be made by Electors chosen for that purpose by the People.”

(The people would vote for an elector, sitting in an electoral college, and they would decide, after 4 or 5 years, if that senator was going to remain a senator or not.)

“4. The Supreme Executive authority of the United States to be vested in a Governor to be elected to serve during good behaviour…”

(Hamilton was proposing that a president serve for life - meaning General Washington.)

“His election to be made by Electors chosen by the people…”

(Not direct election by the people, but chosen by electors. And the electors are chosen directly by the people.)

“The Governor to have a negative upon all laws about to be passed…”

(He would have a veto on all laws.)

“and to have the execution of all laws passed – to be the Commander in Chief of the land and naval forces and of the Militia of the United States…”

(He’s in charge of the army.)

“– to have the direction of war, when authorised or begun – to have with the advice and approbation of the Senate the power of making all treaties – to have the appointment of the heads or chief officers of the departments of finance, war and foreign affairs…”

(The three departments he proposed that General Toussaint have in his government, too.)

“7. The Supreme Judicial authority of the United States to be vested in twelve Judges, to hold their offices during good behaviour…”

(For life.)

“with adequate and permanent salaries.”

During the constitutional convention, they had put forward a plan, that was called the Virginia plan. And it was being attacked all over the place, and people didn’t like this and that. Hamilton gave this speech. After this speech, nobody questioned his plan, and nobody complained about the Virginia plan after that. The interesting thing is, although some of this was voted on, it wasn’t adopted, the part about good behaviour, was agreed to by the Virginia delegation, which included James Madison. Later Hamilton is attacked as being a monarchist, because he proposed a president for life, but the delegation for Virginia agreed to that at the constitutional convention. So that’s the hypocrisy of the attacks on Hamilton on this.

Here's a slide I stole [borrowed] from Sam’s class, on Vattel’s ‘The Laws of Nations’ – Book 1, Chapter 3, #28.

[please check out Sam Labrier’s substack here]

“The perfection of a state, and its aptitude to attain the ends of society, must then depend on its constitution: consequently, the most important concern of a nation that forms a political society, and its first and most essential duty towards itself, is to choose the best constitution possible, and that most suitable to its circumstances…”

(It’s not a utopian idea – of the great democratic idea of Thomas Jefferson, no. You pick the best constitution possible, and the one that’s most suitable to the circumstances you have at the time. But…)

“When it makes this choice, it lays the foundation of its own preservation, safety, perfection, and happiness”

(In other words, the intention of the constitution is what is important, not the actual outline of it. It’s the intention of it that’s important.)

“it cannot take too much care in placing these on a solid basis.”

(Ok, that’s Vattel.)

Now, to duplicate that idea, here’s something. When Hamilton’s in this big fight against Jefferson about the National Bank, they both write an essay. Hamilton writes an ‘Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank’. And you read this and you can just see he’s been studying Vattel, because it’s right out of that book, it’s amazing.

“… that every power vested in a government is in its nature sovereign, and includes, by force of the term, a right to employ all the means requisite and fairly applicable to the attainment of the ends of such power, and which are not precluded by restrictions and exceptions specified in the Constitution, or not immoral, or not contrary to the essential ends of political society…”

(You can’t have the right to employ all means period. No.)

“It may be truly said of every government, as well as of that of the United States, that it has only a right to pass such laws as are necessary and proper to accomplish the objects intrusted to it. For no government has a right to do merely what it pleases … The degree in which a measure is necessary, can never be a test of the legal right to adopt it …”

(Hamilton’s against the idea of necessity - you have to do something because it’s necessary.)

“that must be a matter of opinion, and can only be a test of expediency. The relation between the measure and the end; between the nature of the mean employed toward the execution of a power, and the object of that power must be the criterion of constitutionality…”

(In other words, the intention of the constitution.)

“not the more or less of necessity or utility.”

And that’s a direct attack on Jefferson, who he accuses of doing something only of necessity or utility – a utilitarian. So that’s just Hamilton at his best, and you can see the school of Vattel is where he comes from.

Now just as a little aside, I put in the ‘Constitutional Act for Canada’, for 1791, just to compare it. This is funny.

“Whereas an act was passed in the fourteenth year of the reign of His present Majesty, intitled, An Act for making more effectual provision for the government of the province of Quebec in North America…”

(He’s referring to the Quebec Act of 1774. They’re going to amend it.)

“and whereas the said act is in many respects inapplicable to the present condition and circumstances of the said province…”

(ok so far)

“and whereas it is expedient and necessary that further provision should now be made for the good government and prosperity thereof…”

(Obviously, these guys don’t read Vattel or they don’t read Hamilton – he just told you, you can’t rely on something being expedient or necessary. Yet the British reason for this new act is because it is expedient and necessary. But Hamilton says that can’t be the intention – that’s simply a matter of opinion. So what’s the intention of this thing? Oh, I forgot – the last sentence!)

“may it therefore please your most excellent Majesty that it be enacted…”

(So the intention of the Constitution Act for Canada is to please your majesty. It’s right there in black and white, I don’t lie.)

Now let’s go to the Constitution of Saint-Domingue, that General Toussaint got the central assembly to pass.

“The representatives of the colony of Saint-Domingue, gathered in Central Assembly, have arrested and established the constitutional bases of the regime of the French colony of Saint-Domingue as follows:

Article 3. There cannot exist slaves on this territory, servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French…”

(Very simple. And that’s the intention of the entire constitution. Never before done! I don’t know how long it took for other countries to put that in their constitutions. But the intention is right there.)

“Article 4. All men, regardless of color, are eligible to all employment.

Article 5. There shall exist no distinction other than those based on virtue and talent, and other superiority afforded by law in the exercise of a public function. The law is the same for all whether in punishment or in protection.”

(And I just what to compare it to the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’, from France 1789, when the French revolution started, and it started so well, before it was destroyed by the Jacobins.)

“Article 1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on considerations of the common good.

Article 6. … All citizens, being equal in its eyes, shall be equally eligible to all high offices, public positions and employments, according to their ability, and without other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.”

(Word for word, Toussaint takes the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’ and puts it in his constitution right there, as part of the intention of the constitution.)

Later on [in Saint-Domingue’s constitution]

“Article 19. The colonial regime is determined by laws proposed by the Governor and rendered by a gathering of inhabitants, who shall meet at fixed periods at the central seat of the colony under the title Central Assembly of Saint-Domingue…”

(He rejected Hamilton’s idea of a central committee of the generals. I guess he didn’t trust all of them, and instead he decided to have a central assembly, since that’s what drafted this constitution, so he had confidence in them.)

“Article 22. The Central Assembly of Saint-Domingue shall be composed of two representatives of each department, whom, to be eligible, shall be at least 30 years of age and have resided for 5 years in the colony.

Article 23. The Assembly shall be renewed every two years by half; no one shall be a member for six consecutive years.”

(He doesn’t want the assembly to be there for life.)

“Article 27. The administrative direction of the government shall be entrusted to a Governor who corresponds directly with the government of the Metropole…”

(That means with France, the central government in France.)

“on all matters relative to the interests of the colony…”

(He’s saying, Saint-Domingue is going to have a constitution, but we are part of France, we are a colony of France, we’re not independent. There’s no word about independence anywhere in this document, because France is the only nation on earth that abolished slavery. And Toussaint is committed. His intention is to remain with France.)

“Article 28. The Constitution nominates the citizen Toussaint Louverture, Chief General of the army of Saint-Domingue, and, in consideration for important services rendered to the colony, in the most critical circumstances of the revolution, and upon the wishes of the grateful inhabitants, he is entrusted the direction thereof for the remainder of his glorious life…”

(The interesting thing about Toussaint is, he was never paid! His entire career as General in the army and Lt. Governor, he never accepted a cent – like General Washington, when he was head of the army, he never was paid.)

“Article 29. In the future, each governor shall be nominated for five years, and shall continue every five years for reasons of his good administration.”

(The central assembly will decide, every five years, whether the governor will continue or not.)

[At this point, there is a question from Matt]

Q: ‘Is the central assembly made up of elected people?’

A: ‘Yes, it’s two people elected from each department, so that’s ten people in the assembly – the same way that they elected ten people to an assembly to draft the constitution. It’s the same assembly that he wants to keep. So it’s small but that’s their government that is the best possible and the most suitable – according to Vattel.’

What happens next?

(That’s Napoleon Bonaparte, and the other is General Toussaint.)

1801

After the constitution is proclaimed, General Toussaint receives word that a French expedition was being prepared to sail to Santo Domingo, (the city in the Spanish part) which would be used as a base to launch an invasion of Saint- Domingue. He knows that Napoleon is launching an invasion, before it gets here.

France has a treaty with the United States now, and they have now just signed a peace agreement with Britain, and France’s other colonies have been restored by Britain to France. Bonaparte plus his foreign secretary, Talleyrand, who was not a nice guy (Bonaparte used to call him, ‘shit in silk stockings’, and that’s probably appropriate). Anyway, Bonaparte and Talleyrand wished to re-establish France’s colonial empire. They wanted the money. That was their intention – money.

So, how are they going to do it? Well, first you’ve got to re-colonize Saint-Domingue. Once you do that, you can supply Saint-Domingue and the other colonies with foodstuffs that will be grown in Louisiana. He’d just acquired Louisiana from Spain. This was Bonaparte’s idea of the French colonial empire – Louisiana, which had slavery at that time, would provide the foodstuffs which would then feed the slaves who are worked to death to produce the coffee and everything else on the plantations. President Jefferson, the new president at the time, agreed with France’s aims, due to a recent slave rebellion they had in Virginia, and fears that slaves who had come to the United States with their refugee masters from Saint-Domingue ‘had been infected with the malady of insurrection’, and they were spreading this to the slaves in the United States. So, he was agreeing with France’s policy.

Bonaparte would send a message to General Toussaint that:

“The constitution you made, while including many good things, contains some that are contrary to the dignity and sovereignty of the French people, of which Saint-Domingue forms only a portion. The circumstances in which you found yourself, surrounded on all sides by enemies without the metropole being able to either assist or revictual you, rendered articles of that constitution legitimate that otherwise would not be.”

He doesn’t say what part of the constitution he disagrees with. But (as I showed you), Toussaint modelled it on the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. But maybe that’s what Bonaparte disagrees with. Anyway, we’ll see what Bonaparte’s intentions are a little later.

Bonaparte sends his brother-in-law, General Leclerc, with 45 ships and 12,000 troops to Saint-Domingue, along with secret instructions from Talleyrand. Talleyrand divides it into three periods. The 1st period – occupy the strongholds (the ports, the cities), then arm and organize all the whites, mulattoes and loyal blacks into a National Guard. During the 2nd period – the rebels (those that refused to join this National Guard, but are still fighting him [Toussaint]) shall be pursued to the death. In the 3rd period – Toussaint and his generals shall be deceived and loaded with attentions at first, and then later, arrested and shipped off to France. That was Bonaparte’s plan for how he was going to reconquer Saint-Domingue. He figured this would take maybe two - three weeks. (ok, two, three weeks, huh?!?)

1802

Leclerc arrived in January and began his plan of attack. Toussaint’s massively out-numbered by these crack troops (these were some of Napoleon’s best troops). What his plan was, was when the town was attacked, his garrison in the town would set fire to the town, and then fall back to the interior of the province. And Leclerc would enter a city of smoke and ruins, and then continue his attack, and have the same thing, he was entering cities of smoke and ruins. In February, 13 more ships and 3800 more troops arrived from France for Leclerc. In April, another 10 ships and 5500 more troops arrived. He had 20,000 troops total now.

General Toussaint knew that because France had peace with Britain and with the United States, this meant that France could deal with her colonies without any interference, and he feared even more troops would be sent from France. And remember, Leclerc’s instruction had been – if it had been impossible to get Toussaint to surrender, proclaim that if within a specified time he does not come to take the oath to the Republic, he shall be declared a traitor, after which period a war to the death will begin.

General Toussaint was fearing the disintegration of his army in France’s ‘war to the death’, and so General Toussaint and his generals surrendered, provided that Leclerc guaranteed freedom to all the inhabitants (which he did – at least that’s what he told Toussaint). Because provided that the French Republic (the only nation that had abolished slavery) remained true to that conviction, General Toussaint continued his belief that the only path for freedom for Saint-Domingue, was as a part of France. He and his generals surrendered so that the army wouldn’t be massacred, and Leclerc promised freedom to all the inhabitants. After that, Toussaint was retired to his plantation. Leclerc invited Toussaint to a meeting, and when Toussaint was seated, soldiers rushed in, with bayonets, into the room, arrested Toussaint, chained him, and shipped him off to France.

General Toussaint was kept in prison, at a military fort, in the far east of France in the Jura mountains, near the Swiss border. He was not allowed a hearing or a trial. Bonaparte sent his aide-de-camp to interview Toussaint – to get him to confess that he had sought independence. But General Toussaint only replied truthfully that he had always been faithful to the French Republic. His only request was for a proper tribunal, which Bonaparte wouldn’t give him. While he was in prison, Toussaint dictated his memoirs to the commandant of the jail’s secretary to justify all of his actions since 1802, since Leclerc arrived.

That May, Bonaparte proclaimed that in Tobago, Saint Lucia and Martinique ‘slavery will be maintained’ and ‘the slave trade and their importation into the colonies will take place … in accordance with the laws and regulations prior to 1789’ (prior to the Declaration of the Rights of Man) – going back to the ancient regime. In July, Bonaparte annulled the law of February 1794 of the National Assembly that had abolished slavery in all of France’s colonies, and he re-established slavery in Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue, and maintained slavery in Louisiana. So now you can see what Bonaparte’s disagreement was with Toussaint’s constitution. The minute he got Toussaint out of the way, he re-established slavery in all of the colonies.

When word of this arrived in Saint-Domingue, by October the black regiments in the Saint-Domingue army mutinied and a new rebellion began again. On November 2nd, a conference of all the rebel generals selected Dessalines as their commander-in-chief. So all the regiments were united into one army now to fight Leclerc. That same day that the generals had their conference, Leclerc died of yellow fever. And his second-in-command, Rochambeau, continued, and he continued the campaign of terror – in a war to the death.

[At this point, there is another question from Matt.]

Q: ‘Can you just get back on the time-line, what year was Toussaint’s constitution presented and what year did this all happen?’

A: The constitution was in 1801. July of 1801.)

Q: ‘And everything you just went through with Napoleon, reverting back to this monarchical pro-slavery policy, this was in the same year?’

A: 1802.

Q: ‘And Toussaint was taken hostage, not hostage but imprisoned in France, in what year?’

A: ‘1802. And once Napoleon had him, then he, in May, declared the restoration of slavery. So 1801, there’s no more war in Saint-Domingue, there’s a constitution, there’s an elected government, there’s peace on the island. Toussaint is trying to restart the economy. He’s trying to get some of the ‘big-whites’ to come back, because he needs people who know how to run a plantation. While people are arguing with him, but he says, hey, they know how to do it. There’s no slavery anymore, but they know how to manage it. So in the middle of this, is when Bonaparte wants to re-colonize Saint-Domingue in 1802. January 1802 is when Leclerc actually arrives in Saint-Domingue. So all of this is being prepared in the last part of 1801.’

1803

April 7th 1803, General Toussaint died and was buried in an unmarked grave in the basement of the fort’s chapel – the one man who probably did more to end slavery than anyone else! And the one man who could have kept Saint-Domingue as part of France!

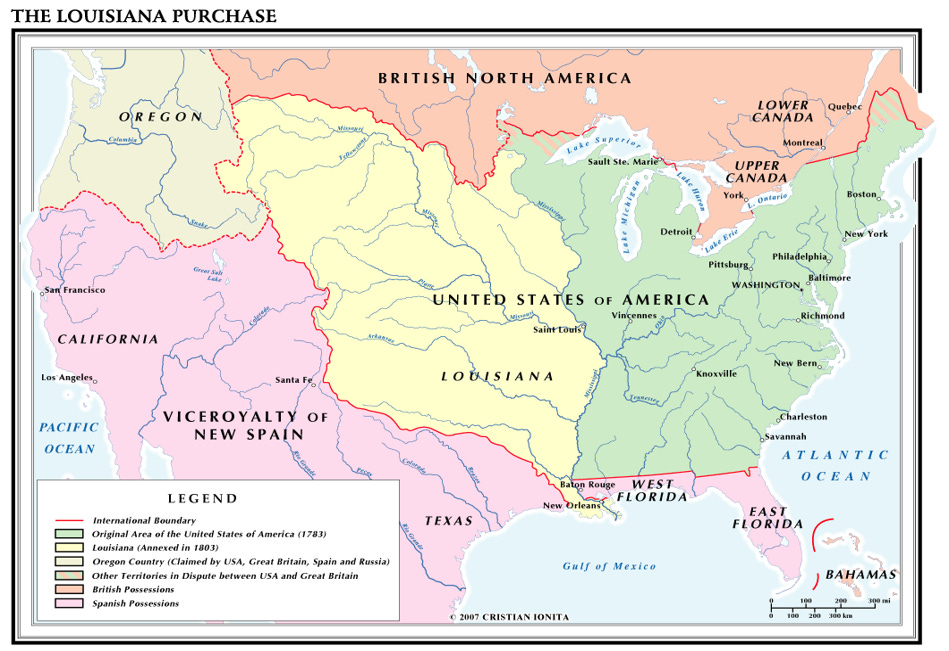

Three days later, Toussaint dies April 7th 1803, and three days later, April 10th 1803, Bonaparte is now thinking about the inevitable coming war with Britain and his need for money to finance it. He’s meeting with his ministers, and he announces that he was thinking of selling Louisiana. Now remember, he thought that this was going to take three weeks to re-conquer it [Saint-Domingue], so this is fifteen months later and he’s farther behind. He’s lost 50,000 men to the fighting and to disease, yellow fever, in Saint-Domingue, and Rochambeau is requesting 35,000 more men and more supplies. Bonaparte cannot afford to lose more men and more money to that quagmire of a war in Saint-Domingue. He decides he’s going to sell Louisiana. He also knew that, in a war with Britain, one of the first things Britain is going to do, would be to seize Louisiana, just as they seized France’s colonies (the island colonies) when they were at war before.

The Americans are looking and saying, either way this is stopping the American western progress. Remember in Pascal’s class [The Rebellions of 1837: Canada's First and Last Revolt] the map of the Quebec Act, where the British have all of British North America, and then if they seize Louisiana, they have all of this again, and the United States – that’s it, they’re not going past the Mississippi.

General Toussaint’s commitment to freedom of Saint-Domingue, and his resistance to the French conquest, even after he was captured with his other generals, led to the selling of Louisiana. And that’s why it is correct to say that without Toussaint Louverture, the United States would never have bought Louisiana, or never been offered. This is April 10th. By May 3rd, they signed an agreement to sell it.

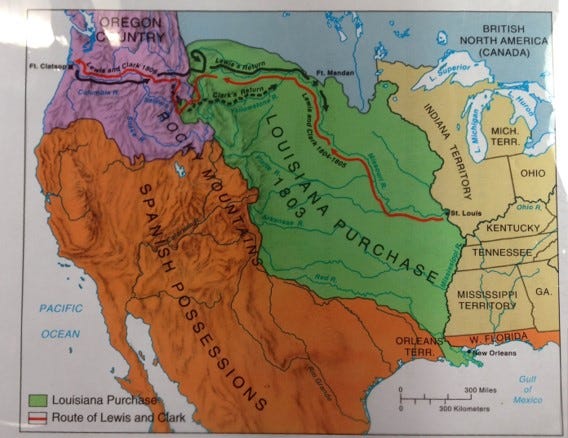

Interestingly, on July 4th, the purchase of Louisiana is announced in the United States. President Jefferson does it at the 4th of July celebration in Washington, DC, in the capital. On July 4th, everyone in the United States learns about the purchase of Louisiana. The very next day, on July 5th, Alexander Hamilton wrote in his newspaper, the New York Evening Post, approving the purchase. A lot of people were against it. Hamilton, the next day wrote and agreed to it. Now you ask, why is that. Well, this goes back a way, to 1793.

One of the American captains, Captain Robert Gray, [I don’t know if he’s any relation to Brian Gray - it’d be nice if he was] was the first American to circumnavigate the globe in 1787-90, on his way to China. The next year, after that, he explored the north-west coast of North America, and he went up and he found the mouth of this great bay with this great river coming into it. And he took readings – the latitude and the longitude, he knew where it was. Later, we call it the Columbia river. He didn’t know where it was, he just knew it was the mouth of this river. In 1793, the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia proposed an expedition to find an overland route to this bay on the Pacific ocean. It got aborted when they discovered that the man they chose to lead the mission was a French agent! But when this thing was proposed by the American Philosophical Society, it was subscribed to by Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and George Washington. They all had the intention that America someday would reach the Pacific ocean – that was in 1793!

Ten years later, when the United States acquires Louisiana from France, Hamilton comes out the next day and approves of it. By November, the British are fighting the French, they’re blockading all the ports of Saint-Domingue, Rochambeau’s got no supplies left, and he surrenders to the British navy. And Britain and France leave Saint-Domingue. On January 1st 1804, Saint-Domingue declares its independence and it is re-named ‘Haiti’ – the original name of the island by the indigenous people that Columbus found. Unfortunately, General Toussaint is not there to lead in the reconstruction, which is a real problem. That’s in January 1804. In May 1804, Napoleon is made Emperor.

Louisiana

Due to General Toussaint’s defence of Saint-Domingue’s constitution and the abolishing of slavery forever, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States. But, not everyone supported the purchase of Louisiana (Hamilton did the very next day). Originally, President Jefferson had sent his envoys, Monroe and Livingston to France with instructions to purchase Florida. He wanted to purchase particularly west Florida, and the island of New Orleans. That’s all he wanted – a port down the Mississippi. These rivers in southern United States all enter into the Gulf of Mexico, but through West Florida. He wanted to have access to these ports [on the Gulf], so they could ship goods from Georgia territory through there. Jefferson only wanted to buy the Floridas, not Louisiana. He still wanted the Mississippi to be the western boundary of the United States. Even after the purchase of Louisiana, Jefferson’s idea was for native Americans living in the Ohio country, to exchange their lands that are east of the Mississippi, for lands west of the Mississippi, with all the settlers there, and then the settlers will go settle east of the Mississippi. He was going to make Louisiana, basically Indian Territory, or native territory, and still have the Mississippi as the boundary of the United States.

Hamilton, as we saw, openly supported the acquisition of Louisiana, but a group of disgruntled ‘federalists’ from New England, around Timothy Pickering, who was now a Senator, (he had been fired [as secretary of state] by President Adams). And the senators around him from New England, they called it the ‘Essex Junto’. They feared that Louisiana was going to change the balance of power in the United States, away from the northern states to the western states. They actually began planning for a secession of the northern New England states out of the Union. They were going to leave the [United] States. This plot came to include the then vice-President Aaron Burr, and the British minister to the United States, Anthony Merry. The plan was that Burr was to become the governor of New York, and with him controlling New York, New York would then join the secession and it would work – they needed New York. But Hamilton helped to stop the election of Burr as New York governor in 1804, just as he’d stopped Burr from becoming president in 1801.

Now Burr is no longer vice-president, he’s not governor of New York, he’s nothing. He then becomes involved in a new plot with General Wilkinson, who’s the head of the United States army, and Charles Williamson, who used to be involved in selling real estate in upstate New York, and now he’s actually on the payroll of the British government (he’s a British agent), and the British minister, Anthony Merry. The plan is to invade and seize Texas from the Spanish, and to join it with Louisiana, and even the western states, like Kentucky and Tennessee, into a new Empire. Burr saw himself as the new Napoleon of this new empire, but he knew there was one man still standing in his way of this – Hamilton.

Burr devised some crazy excuse where he demanded an answer from Hamilton for remarks that Hamilton had made about Burr during the election campaign for governor. If Hamilton had agreed to it, it would have been a humiliating apology from Hamilton, which would have destroyed his remaining influence with the ‘federalists’ in New York, and his leadership in New York would have been removed. That’s what he [Burr] was seeking. Hamilton wrote about this, before the duel with Burr. He wrote some notes on why he agreed to it, even though he was against duelling, and his son had just died in a duel a couple of years earlier. Hamilton wrote:

“the ability to be in future useful, whether in resisting mischief or effecting good, in those crises of our public affairs, which seem likely to happen, would probably be inseparable from a conformity with public prejudice in this particular.”

So that the humiliation of writing an apology to Burr, or not accepting the duel, would have made him useless in ‘resisting mischief’ – meaning stopping the secession. The last letter Hamilton wrote before he died, he was discussing that there was going to be a meeting in November of the ‘federalists’ in Boston, and he was going to attend, to argue against the secession. Even right until his death, he was leading the battle to preserve the Union. This secession of the northern states – this is the effect on Canada.

The effect on Canada

I’ll just use some of the letters of Pickering wrote, just to give you an idea of how open this conspiracy was among this group, the [Essex] junto – from Pickering to Richard Peters on December 24th 1803:

“Although the end of all our Revolutionary labors and expectations is disappointment, and our fond hopes of republican happiness are vanity, and the real patriots of ’76 are overwhelmed by the modern pretenders to that character, I will not yet despair: I will rather anticipate a new confederacy, exempt from the corrupt and corrupting influence and oppression of the aristocratic Democrats of the South. There will be – and our children at farthest will see it – a separation. The white and black population will mark the boundary. The British Provinces, even with the assent of Britain, will become members of the Northern confederacy…”

(he means Canada and Nova Scotia. So somehow he’s already certain that this will happen.)

“A continued tyranny of the present ruling sect will precipitate that event. The patience of good citizens is now nearly exhausted.”

Here’s another one – from Pickering to George Cabot, January 29th 1804:

“But when and how is a separation to be effected? If federalism is crumbling away in New England, there is no time to be lost, lest it should be overwhelmed, and become unable to attempt its own relief. Its last refuge is New England; and immediate exertion, perhaps, its only hope. It must begin in Massachusetts. The proposition would be welcomed in Connecticut; and could we doubt of New Hampshire? But New York must be associated; and how is her concurrence to be obtained? She must be made the centre of the confederacy. Vermont and New Jersey would follow of course, and Rhode Island of necessity … We suppose the British Provinces in Canada and Nova Scotia, at no remote period, perhaps without delay, and with the assent of Great Britain…”

(how does he know that.)

“may become members of the Northern League. Certainly, that government can feel only disgust at our present rulers. She will be pleased to see them crestfallen. She will not regret the proposed division of empire. If with her own consent she relinquishes her provinces, she will be rid of the charge of maintaining them; while she will derive from them, as she does from us, all the commercial returns which her merchants now receive. A liberal treaty of amity and commerce will form a bond of union between Great Britain and the Northern confederacy highly useful to both …”

One last letter – from Pickering to Rufus King, (Rufus King is a close friend of Hamilton) March 4th 1804:

(They’re trying to get Rufus King to join. Hamilton, at the same time, is writing letters to King advising him not to.)

“The Federalists here in general anxiously desire the election of Mr. Burr to the chair of New York…”

(to be the governor of New York)

“for they despair of a present ascendancy of the Federal party. Mr. Burr alone, we think, can break your Democratic phalanx; and we anticipate much good from his success. Were New York detached (as under his administration it would be) from the Virginia influence, the whole Union would be benefited. Jefferson would then be forced to observe some caution and forbearance in his measures. And, if a separation should be deemed proper, the five New England States, New York, and New Jersey would naturally be united. Among those seven states, there is a sufficient congeniality of character to authorize the expectation of practicable harmony and a permanent union, New York the centre...”

The question arises, how did Pickering know that Britain would assent to ceding her North American colonies to this northern confederacy. Meetings among the New England ‘federalist’ congressmen to discuss secession, beginning by at least December 1803, included the traitor, Aaron Burr, (this we know, there is mention of these meetings) and must have included Anthony Merry, the British minister to the United States. The British intention in all this, is not what Pickering’s intention is. The British Empire was in favour of a confederation of the northern states into Canada, to split the Union – but not the other way around – not of annexation of Canada into the Union. No.

This is a quote, (I can’t remember where I got it from, but it’s a British minister, I think, in the 1840s)

“the confederated States of British North America (and he’s including the New England states) would virtually hold the balance of power on the continent, and lead to the restoration of that influence which, more than eighty years ago, England was supposed to have lost.”

This became the future plan of the British Empire – to use Canada as part of the plan to split the United States – which we’ve seen since 1803, was to support northern secession, and since the 1830s, to [also] support southern secession. Therefore, the British Empire could not allow any real republican movement in Canada. It says it would interfere with their future plan. And that’s what Pascal was showing us in his class last week [The Rebellions of 1837: Canada's First and Last Revolt].

The effect on the United States (of the Louisiana Purchase)

Some historians, incorrectly, attribute America’s western expansion to its inherent desire for conquest or empire. This desire for conquest does not occur, until the mistreatment of the natives under the evil Andrew Jackson administration. Some historians, incorrectly, attribute it to a myth – the rugged individual, that man did not shape the wilderness, the wilderness shaped him. And you get this crazy picture of the cowboy, and he drinks whiskey, and he plays cards, and he smokes cigars – the rugged individual, this kind of nonsense. The truth is America’s western progress was a war, and it was fought against the existing world’s empires – the British empire, the French empire, and the Spanish empire. And it was motivated by the idea of a continental republic.

Graham Lowry used to give classes on his book [How the Nation Was Won] and he would always tell people – when the American Revolution started, and the Congress voted to raise an army, and they voted George Washington to be head of it, they created an army, and they called it the Continental Army. They didn’t call it the American Army, they didn’t call it the United States Army, the Colonial Army. Think of it. They called it the Continental Army, and members of the army were the Continental soldiers. They had this conception of a republic, all the way to the Pacific. Graham shows, going all the way back to the early foundings of the colonies in the United States, but also the founding of the United States republic in 1776 with the Continental Army.

I said earlier, on July 4th 1803, the Louisiana Purchase was announced in the United States. The very next day, July 5th, Meriwether Lewis left Washington City and began his expedition of discovery that would take him three and a half years, before he was finally back in Washington City. And this was financed by the United States government. It wasn’t every man for himself, free-enterprise nonsense. This was financed by the government. To show you this nonsense of rugged individual, I just want to look at Meriwether Lewis.

[you can see on the map, that shows from St. Louis all the way to the mouth of the Columbia river and back]

Before he left on this expedition of discovery, he went and studied with members of the American Philosophical Society. He studied with Andrew Ellicott – to learn how to make observations with a sextant, a chronometer, other scientific instruments. You might remember, Andrew Ellicott, along with Benjamin Banneker, laid out the city of Washington, DC. He was the surveyor that did that. Lewis studied with him. Then he went and studied with the foremost mathematician in the United States, Robert Patterson (I think he was also at the University of Pennsylvania, a professor there) – to study how to measure and compute longitude, which if you’ve ever tried to do it, you know it’s difficult. Anyway, Lewis mastered that. He then studied with Dr. Benjamin Rush – to study medicine. You’re going on a trip, two, three years, what happens if someone gets sick. You’ve got to be able to deal with it. So he had to learn medicine and all these diseases and cures, and he had this huge medicine chest he had to take with him. Dr. Benjamin Barton, he studied with – to study botany. All along the trip he was to take samples of all the different plants and leaves from the trees that he saw (the new ones) and bring them back. He studied with Dr. Caspar Wistar – to study anatomy. He actually sent back some live animals and he sent back samples from some. And he also studied fossils with him [Wistar]. I don’t think Meriwether Lewis was a rugged individual. My God! This guy was the best educated man in all of the United States, I think.

Anyway, I just want to show you a quote from him. On his trip, he knew the longitude and latitude of St. Louis (he knew where that was). He went up the Missouri river to Fort Mandan, and he spent the winter there. He knew where the longitude and latitude of that was, that was where a major fur-trading gathering was once a year – all the natives, would come there and trade. That was run by the British. But he knew where that was. And from Captain Gray, he knew exactly where that was [the mouth of the Columbia]. And that’s all he knew, nothing else. He made it all the way up the Missouri, past the Falls, and he’s right here at the end [of the Missouri]. This is before he attempts to cross the mountains, to cross the continental divide, and then he’s got to find the Columbia river, or a tributary of the Columbia river, so he can find his way to the Pacific.

It's August 18th 1805, and it’s his birthday, and he writes this in his journal – four simple little sentences. I’m so impressed with this guy. And he writes:

“this day I completed my thirty-first year and conceived that I had in all human probability now existed about half the period which I am to remain in this sublunary world. I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little, indeed, to further the happiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation. I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now sorely feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended. But since they are past and cannot be recalled, I dash from me the gloomy thought, and resolved in future, to redouble my exertions and at least endeavor to promote those two primary objects of human existence…”

(he means these – to further the happiness of the human race, and, to advance the information of succeeding generations)

“by giving them the aid of that portion of talents which nature and fortune have bestowed on me; or, in future, to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself.”

I just hope that these sans-culottes don’t try to pull down the statue of Lewis and Clark. Thank you.

[Note: Although, there is no written evidence of when Toussaint was born, I would think that, like many French people in those days, his parents named him, based on his birth day’s patron-saint. ‘Toussaint’ means ‘All Saints’, and November 1st, is known as ‘All Saints Day’. So, I have imagined that Toussaint was most likely born on November 1st, and I think perhaps that is why I have felt a connection with him through this passage of time, as November 1st is also my birthday.]