The Unveiling of Canadian History, Volume 4.

To Shining Sea – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana, and the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804.

Part 3 – The Louisiana Frontier

Chapter 36 – The Burr – Hamilton Duel, July 11th 1804

The 1804 meeting between General Wilkinson and Vice President Burr hatched another treasonous plot to split the Union. But one major problem stood in their way - General Hamilton, and so, a way to remove this problem was also hatched.

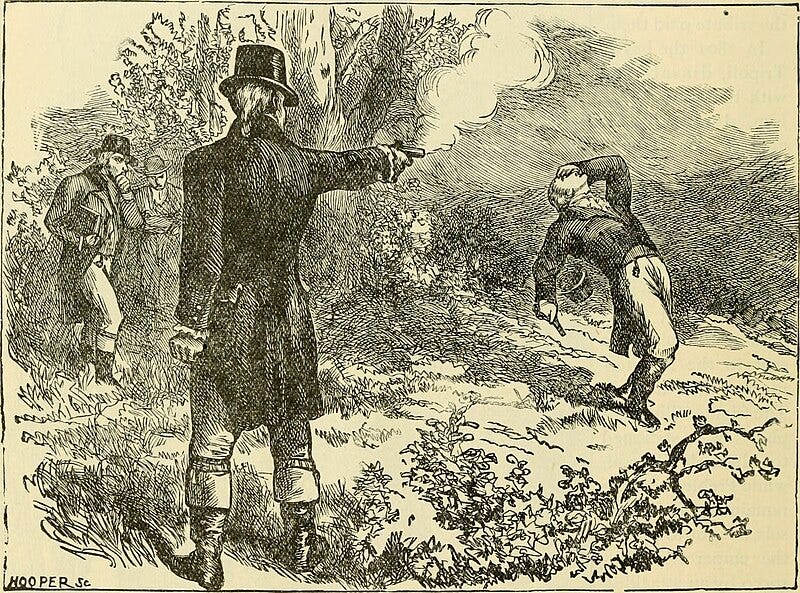

A 1901 Henry Davenport Northrop illustration of the Hamilton-Burr duel of 1804

After France had ceded Louisiana to Governor Claiborne and General Wilkinson for the United States, while he was still in New Orleans, Wilkinson met with Vincente Folch, the Spanish governor of Florida, and tried to collect on $20,000 in arrears he claimed Spain owed him for providing them with written reports and for promoting Spanish interests in the American west. Wilkinson would eventually receive $12,000, and he would provide them with a written report – his ‘Reflections on Louisiana’.

Wilkinson also wrote another version of his ‘Reflections’ for President Jefferson, and left in April 1804 to visit Washington City to advice the President on Louisiana - through his extensive travels through the southwest, Wilkinson knew more than anyone about the new territory. But also he wished to learn the government’s plans for the future, and what information he could forward to the Spanish.

A good picture of Wilkinson is that:

“he almost always cut the cloth of his personal enterprises to fit the pattern of orders that he had received from the federal government. Perhaps Washington, Adams and Jefferson understood his method, believing that he would never go so far as to commit open treachery, although he might use his office as an aid to fattening his purse”. [from Tarnished Warrior, by James Jacobs]

Arriving at New York, and before proceeding to Washington City, on May 23rd 1804, Wilkinson arranged to stay at Burr’s house that evening ‘if it can be done without observation or intrusion’. There is no written record of what was discussed that night, but most probably Wilkinson explained that he had the Spanish problem taken care of – they were ready to believe anything that he told them, and that there was a ready opportunity for an enterprising man to lead an expedition into Spanish territory and to seize a large chunk of their empire.

Also, perhaps the influence of the vice-president might be used to secure the appointment of Wilkinson as the Governor of the Louisiana Territory!!!

Note: A good approximation of Wilkinson’s plan can be shown in a letter from Andrew Ellicott to Secretary of State, Pickering on November 14th 1798. Ellicott had been commissioned by President Washington in 1796 to survey the southern border of the United States with Spain. In the letter, Ellicott was complaining that General Wilkinson and others received annual stipends from Spain, and that:

“the first object of these plotters is to detach the States of Kentucky and Tennessee from the union and place them under the protection of Spain … the design of detaching the western country from the union is but a small part of the general plan which is very extensive and embraces objects of immense magnitude; nevertheless, to ensure success, this point must be first carried; which being effected and by the system of promotion adopted by the court of Madrid, Governor (of Louisiana) Gayoso will be at Quito and the Baron Carondelet at Mexico about the same time: so soon as this arrangement takes place or sooner if the necessary officers can be corrupted a general insurrection will be attempted, and cannot fail of success if the first part succeeds. General Wilkinson is to proceed from Kentucky with a body of troops through the country by the way of the Illinois into New Mexico which will be a central position – the route has been already explored. Nine tenths of the officers of the Louisiana regiment are at this time corrupted and the officers of the Mexican regiment which is now in this country are but little better. The apparent zeal of the Spanish officers on the Mississippi for the dignity of the Crown, is only intended to cover their designs till the great plan which is the establishment of a new empire is brought to maturity…”

While contemplating Wilkinson’s plan, Burr received another visitor, his friend Charles Williamson. Williamson had been the agent for the Pulteney Associates – owners of over 1 million acres in the Genesee valley in western New York, and was transferring his responsibility to Robert Troup, and was preparing for his new career in the British Diplomatic Service – thanks to his friend, Henry Dundas.

Williamson’s assignment (from Dundas) was to recruit recent arrivals to the United States from Britain for an enterprise against the French island possessions in the West Indies; and, if Spain joined with France in the war against Britain, possibly for attacks against Spanish possessions in Florida and Mexico.

Burr and Williamson probably discussed merging the two plans, and Williamson would try to persuade the British government to back this enterprise. But they needed a war with Spain for their plan to succeed, and perhaps, Burr could become the leader of a national army to fight the Spanish! But there was one problem with this plan that Burr foresaw would occur – the reaction of General Hamilton, who had been the senior ranking officer in the Provisional Army, and who would be in charge, in case of a war!

Burr decided that he would demand an answer from General Hamilton regarding remarks that he had made against Burr during the recent New York governor election, and if General Hamilton were to write a humble apology, it would destroy his remaining influence with the ‘federalists’ in New York, and would remove his leadership from a national army in opposing the threat of secession of the northern or the western states.

Burr chose a letter from Dr. Charles Cooper, that had appeared in the Albany Register on April 24th, that referred to a dinner that he had attended in February, at the home of Judge Tayler (Cooper’s father-in-law) with General Hamilton and others, and that read:

“I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.”

James Cheetham, editor of the anti-Burr ‘American Citizen’, would later claim that three of Burr’s supporters had supposedly spent weeks combing newspapers for something that would entitle Burr to issue a challenge. But after all of the many attacks Burr had received from Cheetham in the American Citizen, Burr was offended by the word despicable – attributable to General Hamilton?!?

The history of this April 24th letter, that appeared in the Albany Register, and that contained the word ‘despicable’, starts earlier on April 12th, when Dr. Cooper wrote to Andrew Brown that:

“you will receive some election papers … I presume that you will make use of them to the best advantage. Have them dispersed and scattered as much as possible – the friends of Col. Burr are extremely active and will require all our exertion to put them down – it is believed that most of the reflecting Federalists will vote Lewis. General Hamilton, the Patroon’s [Stephen Van Rensselaer] brother-in-law, it is said has come out decidedly against Burr, indeed when he was here he spoke of him as a dangerous man and ought not to be trusted …”

This (April 12th) letter was printed as an anonymous handbill.

Then on April 21st, Philip Schuyler (General Hamilton’s father-in-law) wrote to the chairman of the Albany Federal Republican Committee, to clarify Hamilton’s position in the election, in regards to (April 12th) Cooper letter, that:

“having seen a letter subscribed with the name of Charles D. Cooper … making sundry assertions relative to the part that General Hamilton … and others would act in the approaching election: I think it proper to mention, that while Chancellor Lansing was considered as the candidate, General Hamilton was in favour of supporting him; but that after the nomination of Chief Justice Lewis, he declared to me that he would not interfere …”

A few days later, on April 23rd, Dr. Cooper responded to Schuyler in a letter, that:

“admitting the letter published to be an exact transcript of the one intended for Mr. Brown, and which, it seems, instead of being delivered according to promise, was embezzled and broken open; I aver, that the assertions therein contained are substantially true, and that I can prove them by the most unquestionable testimony.

I assert that General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared, in substance, that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government. If, Sir, you had attended a meeting of federalists, at the city tavern, where General Hamilton made a speech on the pending election, I might appeal to you for the truth of so much of this assertion as relates to him … I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.”

This letter was published in the Albany Register on April 24th – while the New York elections were taking place, from April 24th to 26th.

The next day, on April 25th, the (Hamilton’s) New-York Evening Post criticized Dr. Cooper for ‘the most palpable falsehood and misrepresentation’; that he knew that ‘few or none of the reflecting Federalist would give their vote to Judge Lewis’; that General Hamilton had repeatedly declared that he would not oppose the election of Colonel Burr in favor of Lewis ‘or any other candidate nominated by the prevailing tyrannical faction, after they drove the Honorable Chancellor Lansing to decline’; and that Cooper had been ‘personally told so in plain and pointed terms by a highly respected Federal character and near connection of General Hamilton (Schuyler).

Burr (who, it should be remembered, was still Vice President) would write to General Hamilton on June 18th – almost 2 months after the New York elections and the publishing of Cooper’s letter (to Schuyler), and asked for:

“a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expressions which could warrant the assertion of Dr. Cooper.”

General Hamilton replied that:

“… I deem it inadmissible, on principle, to consent to be interrogated as to the justness of the inferences, which may be drawn by others, from whatever I may have said of a political opponent in the course of a fifteen years competition …

I stand ready to avow or disavow promptly and explicitly any precise or definite opinion, which I may be charged with having declared of any gentleman. More than this cannot fitly be expected from me; and especially it cannot reasonably be expected, that I shall enter into an explanation upon a basis so vague as that which you have adopted.”

However, Burr insisted, in an answer, that:

“… the common sense of mankind affixes to the epithet adopted by Dr. Cooper the idea of dishonor: it has been publicly applied to me under the sanction of your name. The question is not whether he has understood the meaning of the word or has used it according to syntax and with grammatical accuracy, but whether you have authorised this application either directly or by uttering expressions or opinions derogatory to my honor.”

General Hamilton replied with the same reasoning that:

“… if by a ‘definite reply’ you mean the direct avowal or disavowal required in your first letter, I have no other answer to give than that which has already been given. If you mean any thing different admitting of greater latitude, it is requisite you should explain.”

Burr now replied that:

“… at the close of your letter I find an intimation, that if I should dislike your refusal to acknowledge or deny the charge, you were ready to meet the consequences … yet, as you had also said something … of the indefiniteness of my request; as I believed that your communication was the offspring, rather of false pride than of reflection, and, as I felt the utmost reluctance to proceed to extremities while any other hope remained, my request was repeated in terms more definite. To this you refuse all reply, reposing, as I am bound to presume on the tender of an alternative insinuated in your letter. Thus, Sir, you have invited the course I am about to pursue, and now by your silence impose it upon me.”

Burr continued to insist on a ‘general disavowal’ that General Hamilton had ever intended to impugn his honor in any letter or conversation – something that General Hamilton could not do without appearing to be a coward and liar in the eyes of every man that he had written to or talked to, concerning his principled opposition to Burr.

As Burr had written, in his second letter, that:

“I relied with unsuspecting faith that from the frankness of a soldier and the candor of a gentleman I might expect an ingenuous declaration”,

Burr was not only challenging him as a ‘public opponent’, but also as a ‘soldier’.

Note: General Hamilton’s distrust of Burr originated in his admiration and dedicated defence of General Washington, going as far back (at least) to 1778 - over 25 years!

When General Washington court-martialled General Charles Lee in 1778, Burr wrote a letter to the court-martial defending Lee. Burr became associated with a minority of the officers who disliked and disparaged General Washington’s ability and leadership. In November 1783, after the British had finally evacuated New York, General Washington said farewell to his officers – but Burr was not invited to attend. In December 1783, when General Washington was elected President of the Society of the Cincinnati, some officers refused to join – including Burr.

In 1798, during the Quasi-war with France, Burr was nominated as brigadier-general, but was rejected by General Washington who considered him as too prone to intrigue. General Washington may also have heard the rumors of Burr’s private opinion of him as ‘a man of no talents [who] could not spell a sentence of common English’.

After General Washington’s death, Burr would then join the Society of Cincinnati in 1803, at the time that he was courting ‘federalist’ support for his candidacy for governor, and was being courted for his support for the northern confederacy plot.

On June 28th, General Hamilton began writing ‘some remarks explanatory of my conduct, motives and views’ that:

“… my religious and moral principles are strongly opposed to the practice of duelling, and it would even give me pain to be obliged to shed the blood of a fellow creature in a private combat forbidden by the laws …

I am conscious of no ill-will to Col. Burr, distinct from political opposition, which, as I trust, had proceeded from pure and upright motives. Lastly, I shall hazard much, and can possibly gain nothing by the issue of the interview [i.e. the duel] …

I have resolved, if our interview is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire – and thus giving a double opportunity to Col. Burr to pause and effect. It is not however my intention to enter into any explanations on the ground. Apology, from principle I hope, rather than pride, is out of the question.”

General Hamilton would end his thoughts with the true reason for accepting Burr’s challenge, that:

“to those, who with me abhorring the practice of duelling, may think that I ought on no account to have added to the number of bad examples – I answer that my relative situation, as well in public as private aspects, enforcing all the considerations which constitute what men of the world denominate honor, impressed on me (as I thought) a peculiar necessity not to decline the call. The ability to be in future useful, whether in resisting mischief or effecting good, in those crises of our public affairs, which seem likely to happen, would probably be inseparable from a conformity with public prejudice in this particular.”

[Note: by ‘resisting mischief’, General Hamilton was referring to the part that he would have been called upon to play, in stopping the threat of northern secession.]

On July 10th, in what would be his last letter, General Hamilton wrote to Sedgwick that:

“I have had in hand for some time a long letter to you, explaining my view of the course and tendency of our politics, and my intentions as to my own future conduct. But my plan embraced so large a range that owing to much avocation, some indifferent health, and a growing distaste for politics, the letter is still considerably short of being finished. I write this now to satisfy you, that want of regard for you has not been the cause of my silence. I will here express but one sentiment, which is, that dismemberment of our empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages, without any counterbalancing good; administering no relief to our real disease; which is democracy, the poison of which by a subdivision will only be the more concentered in each part, and consequently the more virulent.”

[Note: General Hamilton had agreed to attend a meeting in Boston in the fall where the proposition of secession would be debated by representatives from all of the New England states.]

Since duelling was illegal in New York, but legal in New Jersey, the duel was set for Wednesday, July 11th across the river from New York at the duelling ground at Weehawken, New Jersey, and they would use John Church’s duelling pistols – the same place where, in 1801, Philip Hamilton had fought (and died) in a duel, and had used the same pistols. Burr came with his second, Willian Van Ness, and General Hamilton was accompanied by his second, Nathaniel Pendleton, and with Dr. Hosack.

When all was ready, both men levelled their pistols, and as General Hamilton pointed his pistol upward, Burr fired, hitting General Hamilton above the hip on his right side, that caused his pistol to fire as he fell forward. He was rowed back to New York, and brought to the home of his friend, William Bayard, where he lay until he died the next afternoon.

General Hamilton’s funeral took place on July 14th, and New York’s Common Council decided to shut down all business that day and that the funeral would be at public expense. The procession was led by New York’s 6th Regiment of Militia and by members of the Society of the Cincinnati, to Trinity Church, where Gouverneur Morris gave the oration.

While being attacked by both the ‘federalist’ and ‘republican’ newspapers, and not wanting to wait until the coroner’s jury indicted him for murder, on the night of July 21st, Burr boarded a boat and was rowed to Perth Amboy, in New Jersey, and then made his way to Philadelphia to stay with friends, and to again meet with Williamson [!!!] before he was to sail back to Britain.

But first, Williamson would meet with Anthony Merry, the British ambassador, who wrote to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Harrowby, on August 6th, that:

“I have just received an offer from Mr. Burr, the actual vice president of the United States (which situation he is about to resign) to lend his assistance to His Majesty’s Government in any manner in which they may think fit to employ him, particularly in endeavouring to effect a separation of the western part of the United States from that which lies between the Atlantic and the mountains, in its whole extant. – His propositions on this and other subjects will be fully detailed to your Lordship by Col. Williamson who has been the bearer of them to me, and who will embark for England in a few days. – It is therefore only necessary for me to add that if, after what is generally known of the profligacy of Mr. Burr’s character, His Majesty’s Ministers should think proper to listen to his offer, his present situation in this country where he is now cast off as much by the democratic as by the federal party, and where he still preserves connections with some people of influence, added to his great ambition and spirit of revenge against the present administration, may possibly induce him to exert the talents and activity which he possesses with fidelity to his employers …’”

Here is proof of Burr’s treason - in the words of the British ambassador himself !!!

On August 2nd, the coroner’s jury found Burr guilty of the misdemeanor of duelling and the felony of murder, but when it was sent to the Grand Jury, it dropped the murder charge (since it had happened in another state) and instead indicted Burr, Van Ness and Pendleton for participating in a duel. Later, on October 23rd, he would be indicted for murder by a grand jury in Bergen county, New Jersey.

Three years later, on November 13th 1807, the indictment was quashed, since General Hamilton ‘did actually die in the City of New York in the State of New York, out of the jurisdiction of this state and a trial upon the said indictment would be totally ineffectual’.

At the end of August, Burr then embarked on a journey south, with Samuel Swartwout, to stay with Pierce Butler at his plantation on Saint Simon’s island in Georgia, and for ten days they explored parts of Florida by horseback and canoe, before returning north to visit his daughter in South Carolina. His reception in the southern states was different, he was ‘overwhelmed with all sorts of attention and kindness – presents are daily sent’. While Burr was away, his house and furniture in New York City had been sold to satisfy his creditors.

Upon his return to Washington City, both Madison and Gallatin made a point of greeting him, and he would also be invited for dinner with the President. On November 5th, he took his seat in the Senate, where he would stay – immune from subpoenas, until the end of this session of Congress and the end of his term as vice-president.

On March 2nd 1805, Burr gave his farewell speech to the Senate, and left Washington City before the inauguration of Thomas Jefferson for a second term as president, and also before his immunity from arrest expired. Burr secretly travelled to Philadelphia where he held talks with British Minister Merry – about Burr’s plans to become the ‘Napoleon’ of a new empire – of Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana and Spanish Texas.

On April 10th, Burr left Philadelphia to travel to Pittsburgh, and by the first of May, he was travelling by boat down the Ohio river on his way to New Orleans, on his path of ‘treason in America’!

At the same time, Lewis and Clark were about to depart Fort Mandan – on their way to the source of the Missouri river and then across the continental divide to the western ocean, on their path of great discovery for America!

[next week - chapter 37 - The Discovery of the Western Ocean, November 17th 1805]

For those who may wish to support my continuing work on ‘The Unveiling of Canadian History’, you may purchase my books, that are available as PDFs and Paperback (on Amazon) at the Canadian Patriot Review :

Volume 1 – The Approaching Conflict, 1753 – 1774.

Volume 2 – Forlorn Hope – Quebec and Nova Scotia, and the War for Independence, 1775 – 1785.

And hopefully,

Volume 3 – The Storming of Hell – the War for the Territory Northwest of the Ohio, 1786 – 1796, and

Volume 4 – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana – the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804,

may also appear in print, in the near future, while I continue to work on :

Volume 5 – On the Trail of the Treasonous, 1804 - 1814.