The Unveiling of Canadian History, Volume 4.

To Shining Sea – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana, and the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804.

Part 3 – The Louisiana Frontier

Chapter 35 - The New York Governor Election, April 24 – 26, 1804

A treasonous plot to split the United States in two was being planned by the ‘Essex Junto’ of New England, led by Timothy Pickering, that would be a part of the plan of the British Empire to absorb New England into her other North American possession - Canada!

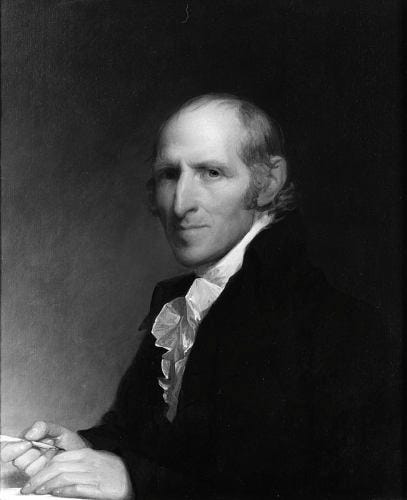

Timothy Pickering

While General Hamilton was speaking before the New York Supreme Court, on February 14th, a caucus of the ‘republican’ state legislators were also meeting in Albany to nominate George Clinton to be their candidate for Governor in the upcoming state elections. But Clinton declined the nomination, having been assured that he would be accepted as the ‘republican’ candidate for vice-president, running with President Jefferson.

1804 was an election year – and the ‘republicans’ were anticipating the re-election of President Jefferson. New York was a key battle ground in the election of 1800 and would be a battle ground of a different kind in 1804.

George Clinton had been New York’s Governor for 18 years from 1777 until 1795, when John Jay was twice elected governor before retiring from all public service. In 1801, Clinton again was elected New York governor – defeating Stephen Van Rensselaer (who had been Jay’s Lieutenant-Governor and was Alexander Hamilton’s brother-in-law).

In 1803, DeWitt Clinton, nephew and secretary of George Clinton, was appointed mayor of New York City, and together with his uncle, controlled fifteen thousand civil and military patronage appointments. DeWitt Clinton wished to have his aging 64-year-old uncle become the ‘republican’ vice-presidential candidate with Jefferson in 1804, and therefore wished to remove any potential rivals for his future control of the Clinton political machine in New York – which meant eliminating any support for Aaron Burr.

To attack Burr, DeWitt Clinton would use the newspaper ‘The American Citizen’, edited by James Cheetham. President Jefferson was a subscriber to the American Citizen (as well as Hamilton’s New-York Evening Post) throughout his presidency, writing to Cheetham, on April 23rd 1802, that:

“I shall be glad to receive your daily paper by post, as usual … it is proper I should know what our opponents say and do; yet really make a matter of conscience of not contributing to the support of their papers. I presume Coleman [i.e. editor of the Evening Post] sends you his paper, as I understand the printers generally do to one another. I shall be very glad to pay you for it, & thus make my contribution go to the support of yours instead of his press. If therefore, after using it for your own purposes you will put it under cover with your American Citizen to me, it shall be paid for always with yours.”

In June 1802, Cheetham published the pamphlet ‘A View of the Political Conduct of Aaron Burr’, accusing Burr of having secretly schemed to steal the presidential election away from Jefferson in 1800, and of plotting to gain ‘federalist’ support to run against Jefferson in 1804.

In October, Burr and his supporters answered Cheetham’s accusations by founding their own newspaper the ‘Morning Chronicle’, edited by Dr. Peter Irving; and by publishing their own pamphlet, ‘An Examination of the Various Charges Exhibited Against Aaron Burr, signed by Aristides’, that was written by William Van Ness.

Note: Peter Irving’s younger brother, Washington Irving, would write a series of letters – satires on the current culture of New York City, signed by Jonathan Oldstyle, that were printed in the Morning Chronicle in 1802-03.

After reading Aristides’ pamphlet, George Clinton wrote to the President to claim his innocence, because the pamphlet charged Clinton with expressing ‘sentiments highly derogatory to your political character and inconsistent with private friendship’. On December 31st 1803, after also reading the pamphlet, President Jefferson answered that:

“little hints & squibs in certain papers had long ago apprised me of a design to sow tares between particular republican characters. But to divide those by lying tales whom truths cannot divide, is the hackneyed policy of the gossips of every society.”

On January 26th 1804, Aaron Burr arranged for a meeting with President Jefferson in order to tell him that since becoming vice-president (according to Jefferson’s Anas) that :

“those great families [i.e the Livingstons and Clintons] had become hostile to him … (and) he believed it would be for the interest of the republican cause for him to retire; that a disadvantageous schism would otherwise take place; but that were he to retire, it would be said he shrank from the public sentence, which he would never do; that his enemies were using my name to destroy him, and something was necessary from me to prevent and deprive them of that weapon, some mark of favor from me which would declare to the world that he retired with my confidence.”

Jefferson replied that:

“I had never interfered directly or indirectly with my friends or any others, to influence the election either for him or myself; that I considered it my duty to be merely passive … that in the election now coming on, I was observing the same conduct, held no councils with anybody respecting it, nor suffered anyone to speak to me on the subject, believing it my duty to leave myself to the free discussion of the public … (but) that I had myself contemplated his appointment to one of the great offices, in case he was not elected Vice-President …”

Further on, President Jefferson wrote that:

“I had never seen Colonel Burr till he came as a member of the Senate. His conduct very soon inspired me with distrust. I habitually cautioned Mr. Madison against trusting him too much … with these impressions of Colonel Burr, there never had been an intimacy between us, and little association. When I destined him for a high appointment, it was out of respect for the favor he had obtained with the republican party, by his extraordinary exertions and successes in the New York election in 1800.”

President Jefferson was diplomatically washing his hands of Burr and was not having anything to do with his future.

After Clinton had declined the nomination for governor, the ‘republican’ legislators in Albany met again the next day, on February 15th, and nominated John Lansing, New York State Chancellor, to be their candidate.

The next day, on February 16th, a group of leading ‘federalists’ in Albany, who were in such disarray that they had not fielded a candidate of their own, met to discuss what role, if any, they should play in the campaign for governor, and, whether as some wished - to support Burr for governor.

Being in Albany, General Hamilton attended the meeting and presented his ‘reasons why it is desirable that Mr. Lansing rather than Col. Burr should succeed’. He spoke against the expected campaign of Burr for governor, that:

“Col. Burr has steadily pursued the track of democratic policies. This he has done either from principle or from calculation. If the former he is not likely now to change his plan, when the federalists are prostrate and their enemies predominant. If the latter, he will certainly not at this time relinquish the ladder of his ambition and espouse the cause or views of the weaker party ... The effect of his elevation will be to reunite under a more adroit, able, and daring chief the now scattered fragments of the democratic party ... if Lansing is governor his personal character affords some security against pernicious extremes, and at the same time renders it morally certain, that the democratic party already much divided and weakened will smoulder and break asunder more and more ...”

He touched on his real reason for opposing Burr – his fear of secession of New England from the Union, that:

“a further effect of his elevation by the aid of federalists will be to present to the confidence of New England a man already the man of the democratic leaders of that country, and towards whom the mass of the people have no weak predilection as their countryman – as the grandson of President Edwards, and the son of President Burr.”

Note: Aaron Burr’s father, Rev. Aaron Burr Sr. was born in Connecticut and was president of New Jersey College (later, Princeton University) 1748-57. Burr’s mother, Esther Edwards, was also from Connecticut and was the daughter of Rev. Jonathan Edwards of the ‘Great Awakening’, who became president of New Jersey College, after the death of Burr Sr. in 1758.

Hamilton warned that:

“the ill opinion of Jefferson and jealousy of the ambition of Virginia is no inconsiderable prop of good principles in that country. But these causes are leading to an opinion that a dismemberment of the Union is expedient. It would probably suit Mr. Burr’s views to promote this result to be the chief of the northern portion and, placed at the head of the state of New York, no man would be more likely to succeed.”

A number of New England ‘federalists’ in Congress, called the ‘Essex Junto’, disillusioned from their defeat over the constitutionality of the Louisiana treaty, began discussing the idea of seceding from the Union. But for their plan to work, they needed the agreement of New York – and so they sought out Burr as part of their plan. While General Hamilton had not received any letters concerning this plan, he obviously knew what was being discussed – and his reason for opposing any federalist support for Burr!

Note on the plan for secession of New England:

The plan for secession from the Union, can be seen in the following letters.

[from Senator Timothy Pickering to Richard Peters on December 24th 1803] –

“Although the end of all our Revolutionary labors and expectations is disappointment, and our fond hopes of republican happiness are vanity, and the real patriots of ’76 are overwhelmed by the modern pretenders to that character, I will not yet despair: I will rather anticipate a new confederacy, exempt from the corrupt and corrupting influence and oppression of the aristocratic Democrats of the South. There will be – and our children at farthest will see it – a separation. The white and black population will mark the boundary. The British Provinces [i.e. Canada and Nova Scotia], even with the assent of Britain, will become members of the Northern confederacy. A continued tyranny of the present ruling sect will precipitate that event. The patience of good citizens is now nearly exhausted …”

[from Timothy Pickering to George Cabot, January 29th 1804] –

“But when and how is a separation to be effected? … (if) federalism is crumbling away in New England, there is no time to be lost, lest it should be overwhelmed, and become unable to attempt its own relief. Its last refuge is New England; and immediate exertion, perhaps, its only hope. It must begin in Massachusetts. The proposition would be welcomed in Connecticut; and could we doubt of New Hampshire? But New York must be associated; and how is her concurrence to be obtained? She must be made the centre of the confederacy. Vermont and New Jersey would follow of course, and Rhode Island of necessity …

We suppose the British Provinces in Canada and Nova Scotia, at no remote period, perhaps without delay, and with the assent of Great Britain, may become members of the Northern League. Certainly, that government can feel only disgust at our present rulers. She will be pleased to see them crestfallen. She will not regret the proposed division of empire. If with her own consent she relinquishes her provinces, she will be rid of the charge of maintaining them; while she will derive from them, as she does from us, all the commercial returns which her merchants now receive. A liberal treaty of amity and commerce will form a bond of union between Great Britain and the Northern confederacy highly useful to both …”

[from Timothy Pickering to Rufus King, March 4th 1804) –

“The Federalists here in general anxiously desire the election of Mr. Burr to the chair of New York; for they despair of a present ascendancy of the Federal party. Mr. Burr alone, we think, can break your Democratic phalanx; and we anticipate much good from his success. Were New York detached (as under his administration it would be) from the Virginia influence, the whole Union would be benefited. Jefferson would then be forced to observe some caution and forbearance in his measures. And, if a separation should be deemed proper, the five New England States, New York, and New Jersey would naturally be united. Among those seven states, there is a sufficient congeniality of character to authorize the expectation of practicable harmony and a permanent union, New York the centre...”

[from the journal of Senator William Plumer) –

In the winter of 1803-04, Senators Pickering (MA), Hillhouse (CT) and Plumer (NH) dined with Burr, and Hillhouse ‘unequivocally declared that it was his opinion that the United States would soon form two distinct governments’; that ‘Burr conversed very freely on the subject … and the impression made on his mind was, that Burr not only thought a separation would not only take place but that it was necessary’. He further wrote that ‘yet, on returning to my lodgings and critically analyzing his words, there was nothing in them that committed him in any way.'

The question arises as to how Pickering knew that Britain would assent to ceding her North American colonies to a northern confederacy. Meetings among New England ‘federalist’ politicians to discuss secession (beginning by at least December 1803) must have included Anthony Merry, the British minister to the United States. This became the future plan of the British Empire – to use Canada as part of the plan to split the United States.

On February 18th, fifteen dis-satisfied ‘republicans’ met and nominated Burr as their candidate for governor! Although the number of Burr’s supporters was much smaller than those of Lansing, they had hoped to gather support from the dismayed ‘federalists’. Adding to the turmoil, that evening, after having been ordered to issue a statement that he would be a model republican for his three-year term as governor (i.e. be obedient to DeWitt Clinton), Lansing withdrew his name from the race – not wishing to lose his independence. The next day, the ‘republicans’ now nominated as candidate for governor, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Morgan Lewis – who had presided over the Croswell trial and who had heard the appeal for a new trial from General Hamilton!

And on February 25th, a caucus of ‘republicans’ in Congress met to nominate their candidates for president – President Jefferson won unanimously, and for vice-president – George Clinton won with 67 votes over John Breckinridge with 21 votes, while Burr received not one vote – showing his ouster from the ‘republican’ party.

On February 24th, General Hamilton wrote to Rufus King, to encourage him to run for governor, that:

“you will have heard, before this reaches you, of the fluctuations and changes which have taken place in the measures of the reigning party, as to a candidate for Governor; and you will probably have also been informed that pursuant to the opinions professed by our friends, before I left New York, I had taken an open part in favour of Mr. Lansing … but now that Chief Justice Lewis is the competitor, the probability of success in my judgment inclines to Mr. Burr …

thus situated, two questions have arisen. 1. – whether a federal candidate ought not to be run as a mean of defeating Mr. Burr and of keeping the federalists from becoming a personal faction allied to him. 2. – whether in the conflict of parties ⟨as⟩ they now stand, the strongest of them disconnected and disjointed, there would not be a considerable hope of success for a Federal candidate … it is agreed that if an attempt is to be made, You must be the candidate.”

But King replied to Hamilton on March 1st that:

“after maturely reflecting upon the subject, and consulting one or two of our friends here, I am confirmed in the sentiment that I ought not to consent to be a candidate for the Governor.”

After that attempt, General Hamilton would remain neutral and would not interfere in the election as it became a bitter battle between the Morning Chronicle (pro-Burr) and the American Citizen (pro-Clinton) newspapers. Hamilton had other plans.

Judge Kent later wrote, in his memoirs, of a meeting with General Hamilton on April 21st, shortly before the elections, that:

“the impending election exceedingly disturbed him, and he viewed the temper, disposition, and passions of the times as portentous of evil, and favorable to the sway of artful and ambitious demagogues. His wise reflections, his sober views, his anxiety, his gentleness, his goodness, his Christian temper, all contributed to render my solitary visit inexpressibly interesting. At that time he revealed to me a plan he had in contemplation, for a full investigation of the history and science of civil government, and the practical results of the various modifications of it upon the freedom and happiness of mankind. He wished to have the subject treated in reference to past experience, and upon the principles of Lord Bacon’s inductive philosophy. His object was to see what safe and salutary conclusions might be drawn from an historical examination of the effects of the various institutions heretofore existing, upon the freedom, the morals, the prosperity, the intelligence, the jurisprudence, and the happiness of the people. Six or eight gentlemen were to be united with him in the work, according to his arrangement, and each of them was to take his appropriate part and to produce a volume … The conclusions to be drawn from these historical reviews, he intended to reserve for his own task, and this is the imperfect outline of the scheme which then occupied his thoughts.”

The New York elections took place over April 24th to 26th, and while Burr carried New York City, he could not carry the northern counties, losing the election – with 28,000 votes to 35,000 votes for Lewis.

According to the Evening Post, Burr lost because of Cheetham and the American Citizen and ‘the very extraordinary attacks on his private character, which were circulated with an industry and an expense hitherto unexampled’. With the ‘republican’ Lewis as Governor, New York would again insure the election of Jefferson as president.

The plot for a northern confederacy was temporarily set back, but on May 2nd, the Evening Post reprinted an essay from the Boston Repertory, that the way to stop the aristocratical power of Virginia and the southern states was an amendment to the constitution that eliminated their representation in Congress for the three-fifths of its slave population.

On June 20th, the Massachusetts General Court passed a ‘resolve for proposing an amendment to the constitution of the United States respecting an equal representation in Congress’ that:

“… whereas the said provisions have been rendered more injurious, by important political changes, introduced during the present administration, in the purchase of Louisiana, an extensive country, which will require great numbers of slaves for its cultivation, and when admitted into the Union, agreeably to the cession, will contribute by the number of its slaves, to destroy the real influence of the Eastern States in the National Government …”

This resolution was introduced in the United States Senate by Pickering on December 7th, where it was read and ordered to lie for consideration.

[next week - chapter 36 - The Burr – Hamilton Duel, July 11th 1804]

For those who may wish to support my continuing work on ‘The Unveiling of Canadian History’, you may purchase my books, that are available as PDFs and Paperback (on Amazon) at the Canadian Patriot Review :

Volume 1 – The Approaching Conflict, 1753 – 1774.

Volume 2 – Forlorn Hope – Quebec and Nova Scotia, and the War for Independence, 1775 – 1785.

And hopefully,

Volume 3 – The Storming of Hell – the War for the Territory Northwest of the Ohio, 1786 – 1796, and

Volume 4 – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana – the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804,

may also appear in print, in the near future, while I continue to work on :

Volume 5 – On the Trail of the Treasonous, 1804 - 1814.