To Shining Sea - Chapter 34

General Hamilton’s Defence of the Truth, February 14th – 15th, 1804

The Unveiling of Canadian History, Volume 4.

To Shining Sea – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana, and the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804.

Part 3 – The Louisiana Frontier

Chapter 34 - General Hamilton’s Defence of the Truth, February 14th – 15th, 1804

One of the most important court cases in the United States, regarding the defence of freedom of the press, and the defence of truth, was addressed by General Alexander Hamilton.

[Note: An excellent article about the importance of the Croswell case and Alexander Hamilton is written by Nancy Spannaus - ‘Hamilton’s Fight for the Truth Standard’.]

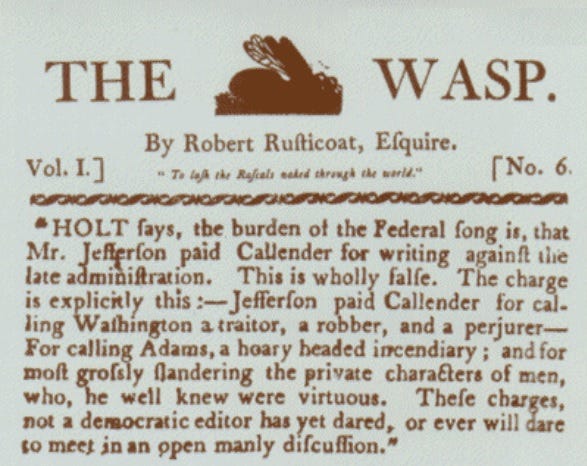

The September 1802 edition of ‘The Wasp’.

While the United States Congress was passing legislation for the government of Louisiana, the New York State Supreme Court was meeting in the state capital of Albany, on February 13th, to hear what would become a very important case – Henry Croswell’s appeal for a new hearing. One of Croswell’s attorneys was General Alexander Hamilton, who agreed to present his appeal, without fee.

Note: Henry Croswell had started a small ‘federalist’ news sheet, The Wasp, to counter-attack a small ‘republican’ news sheet, The Bee, run by Charles Holt, in Hudson, New York. On September 9th 1802, Croswell repeated a charge that had also appeared in the New York Evening Post that Jefferson had paid James Callender to attack President Adams and his administration. Croswell added that Jefferson had also paid Callender to attack General Washington, calling him ‘a traitor, robber, and perjurer’.

Although the ‘republicans’ opposed the Sedition Act, they were not opposed to targeting the press by using similar state laws. On January 11th 1803, Croswell was arrested and charged with:

“being a malicious and seditious man, and of depraved mind and wicked and diabolical disposition, and deceitfully, wickedly and maliciously devising, contriving and intending, toward Thomas Jefferson, Esquire, President of the United States of America, to detract from, scandalize, traduce and vilify, and to represent him, the said Thomas Jefferson, as unworthy of the confidence, respect and attachment of the people of the said United States …”

The trail began on July 11th, with the Attorney General, Ambrose Spencer, prosecuting and with the Supreme Court Judge, Morgan Lewis, presiding. Croswell’s attorney wished to bring James Callender from Richmond, Virginia to testify on the truth of the allegations, but before this could be done, Callender died (mysteriously) on July 17th – he drowned in the James river, in 3 feet of water, apparently too drunk to be able to save himself!

The jury was instructed by Justice Lewis that they ‘were judges of the fact and not of the truth or intent of the publication’, and Croswell was found guilty.

The appeal began on February 13th with Spencer defending the charge to the jury that truth was irrelevant in a public trial, dismissing an opinion by former chief justice, John Jay, that the jury in a libel trial could consider the motives and facts of the case, and citing examples from English common law including the opinion of Lord Mansfield!

General Hamilton spoke for 6 hours over two days – February 14th and 15th, not as a defence of the freedom of the press (as some people have asserted) but speaking of the limits of freedom of the press.

He began his defence that:

“in speaking thus for the freedom of the press, I do not say there ought to be unbridled licence or that the characters of men who are good, will naturally tend eternally to support themselves. I do not stand here to say that no shackles are to be laid on this licence. I consider this spirit of abuse and calumny as the pest of society.”

Instead, General Hamilton spoke in defence of admitting truth as defence in libel cases – in defence of publishing the truth, but, most importantly, to use truth and freedom of the press to defend President Washington!

He continued that:

“I know the best of men are not exempt from the attacks of slander. Though it pleased God to bless us with the first of characters [i.e. Washington], and though it has pleased God to take him from us, and this band of calumniators, I say, that falsehood eternally repeated would have effected even his name. Drops of water in long and continued succession will wear out adamant. This therefore cannot be endured. It would be to put the best and the worst on the same level. I contend for the liberty of publishing truth, with good motives, and for justifiable ends, even though it reflect on government, magistrates, or private persons. I contend for it under the restraint of our tribunals – when this is exceeded, let them interpose and punish …”

General Hamilton was inferring that in a new trial, it should be the right of Croswell to prove the truth of his writing that Jefferson had paid Callender to slander General Washington – and that it may include the testimony of President Jefferson!!!

General Hamilton next spoke to show that it is intention that must be considered in the crime, that:

“my definition of a libel is … a slanderous or ridiculous writing, picture, or sign, with a malicious or mischievous design or intent, towards government, magistrates, or individuals … when we come to investigate, every crime includes an intent. Murder consist in killing a man with malice propense. Manslaughter, in doing it without malice, and at the moment of an impulse of passion. Killing may even be justifiable if not praise-worthy, as in defence of chastity about to be violated. In these cases, the crime is defined, and the intent is always deemed the necessary ingredient … killing therefore is not a crime, but it becomes so in consequence of the circumstances annexed …

The law contemplates the intent … it is impossible to separate a crime from the intent … It may, as a general and universal rule, be asserted, that the intention is never excluded in the consideration of a crime. The only case resorted to, and which is relied on by the opposite side (for all the others are built upon it) to show a contrary doctrine, was a star chamber decision … Unless therefore it can be shown that there is some specific character of libel, that will apply in all cases, intent, tendency, and quality, must all be matters of fact for a jury. There is therefore nothing which can be libel, independent of circumstances; nothing which can be so called in opposition to time and circumstances …

This then is a decision, as we contend, that not only the intent, but the truth is important to constitute a crime, and nothing has been shown against it … Its being a truth is a reason to infer, that there was no design to injure another … falsehood must be the evidence of the libel … for, whether the truth be a justification, will depend on the motives with which it was published …

Personal defects can be made public only to make a man disliked. Here then it will not be excused: it might however be given in evidence to shew the libellous degree. Still however it is a subject of enquiry. There may be a fair and honest exposure. But if he uses the weapon of truth wantonly; if for the purpose of disturbing the peace of families; if for relating that which does not appertain to official conduct, so far we say the doctrine of our opponents is correct. If their expressions are, that libellers may be punished though the matter contained in the libel be true, in these I agree. I confess that the truth is not material as a broad proposition respecting libels. But that the truth cannot be material in any respect, is contrary to the nature of things. No tribunal, no codes, no system can repeal or impair this law of God, for by his eternal laws it is inherent in the nature of things …”

General Hamilton continued to show the constitutionality of admitting truth as evidence, stating that:

“we find not only the intent, but the truth may be submitted to the jury, and that even in a justificatory manner. This, I affirm, was on common law principles. It would, however, be a long detail to investigate the applicability of the common law, to the constitution of the United States. It is evident, however, that parts of it, use a language which refers to former principles … such is the general tenor of the constitution of the United States, that it evidently looks to antecedent law. What is, on this point, the great body of the common law? Natural law and natural reason applied to the purposes of society … What have the court done here? Applied moral law to constitutional principles, and thus the judges have confirmed this construction of the common law, and therefore, I say, by our constitution it is said, the truth may be given in evidence … Never can tyranny be introduced into this country by arms; these can never get rid of a popular spirit of enquiry; the only way to crush it down is by a servile tribune. It is only by the abuse of the forms of justice that we can be enslaved …”

General Hamilton would end his defence by again defending General Washington, that:

“it is desirable that there should be judicial grounds to send it back again to a jury. For surely it is not an immaterial thing that a high official character should be capable of saying anything against the father of this country. It is important to have it known to the men of our country, to us all, whether it be true or false; it is important to the reputation of him against whom the charge is made, that it should be examined. It will be a glorious triumph for truth, it will be happy to give it a fair chance of being brought forward; an opportunity in case of another course of things, to say, that the truth stands a chance of being a criterion of justice …

But the Attorney General has taken vast pains to celebrate Lord Mansfield’s character. Never till now did I hear that his reputation was high in republican estimation; never till now did I consider him as a model for republican imitation. I do not mean however to detract from the fame of that truly great man, but only conceived his sentiments were not those fit for a republic.”

At the end of May, Judges Kent and Thompson agreed with General Hamilton’s argument and the need for a new trial, but Judge Lewis and Henry Livingston disagreed – with a tie vote, the conviction stood. Livingston had at first agreed with Kent (and Croswell was released on $500 bail and told to appear for a new trial at the next Circuit Court) but then he suddenly reversed his opinion and agreed with Lewis (who was running for Governor and did not wish this case to interfere with his chances) – Livingston would later be appointed to the United States Supreme Court by President Jefferson in November 1806.

Although the court ruled against a new trail, no attempt was ever made to punish Croswell for the guilty verdict in the original trial, and the matter was quietly dropped. Van Ness, another member of the defence team and a member of the Assembly, introduced a bill modeled on General Hamilton’s speech.

In May 1805, the New York Legislature enacted a law allowing truth as a defence to a libel charge ‘where published with good motive for justifiable ends’ and so Croswell was awarded a new trial, but the prosecution never attempted to retry.

[next week - chapter 35 - The New York Governor Election, April 24 – 26, 1804]

For those who may wish to support my continuing work on ‘The Unveiling of Canadian History’, you may purchase my books, that are available as PDFs and Paperback (on Amazon) at the Canadian Patriot Review :

Volume 1 – The Approaching Conflict, 1753 – 1774.

Volume 2 – Forlorn Hope – Quebec and Nova Scotia, and the War for Independence, 1775 – 1785.

And hopefully,

Volume 3 – The Storming of Hell – the War for the Territory Northwest of the Ohio, 1786 – 1796, and

Volume 4 – Ireland, Haiti, and Louisiana – the Idea of a Continental Republic, 1797 – 1804,

may also appear in print, in the near future, while I continue to work on :

Volume 5 – On the Trail of the Treasonous, 1804 - 1814.