THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL OF ATHENS

"A little learning is a dang'rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again."

[from ‘An Essay on Criticism’, by Alexander Pope]

Part 1 – a Knowledge of the Causes

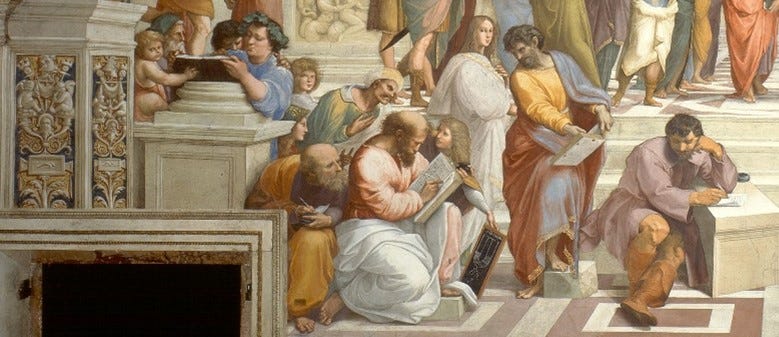

The year, 2020, marked the 500th anniversary of the death of the great Florentine artist Raffaello Sanzio. One of his most famous works is the fresco painted at the Vatican in the Stanza della Segnatura, originally called ‘Causarum Cognitio’ or ‘Knowledge of the Causes’, and today it is called the ‘School of Athens’. Let us then, in Raphael’s memory, take a new look at his fresco, in order to try to learn from one of the artists of the Florentine renaissance, how they succeeded in pulling their culture out of a dark age.

When I first began to try to identify the different personalities in this fresco, more than 20 years ago now, I found that the ‘so-called’ accepted interpretations of this identification were haphazard, disjointed and unconnected, and were in fact more confusing than helpful. So, following the lead of Mr. Lyndon LaRouche, I threw these interpretations out the window, and started afresh. While my interpretation may not be exactly that of Raphael’s, at least I have tried to do so in a coherent way, with a respect to the actual history involved, in telling my tale.

The following is from Lyndon LaRouche: from the book ‘The Economics of the Noösphere’ – ‘Shrunken Heads In America Today’ – March 2001:

“Look at Raphael’s ‘School of Athens’. I propose that the reader work through the following exercise.

Make a list of each of the historical figures represented. Take a map of the relevant area of the Mediterranean and its littoral for the period from the time of Homer through the entirety of the Classical and Hellenistic phases of Greek and related culture. Locate the place and date of existence of each figure on that map. Then identify the relationship among these figures in terms of those leading ideas which bear upon the irreconcilable dispute between the cognitive Plato and his opponent, the reductionist Aristotle. Ask yourself, is the gloomy figure in the foreground, perhaps the Classical Platonist Raphael’s recognition of the Romantic tendencies in his contemporary, Michelangelo?

In this collection as a whole, there are sequences of time, and sequences of ideas, or beliefs, such as Aristotle’s, substituted for ideas. In the painting, these figures are represented as contemporaries, as if the entire period represented by these figures’ mortal lives, had been compacted into a kind of simultaneity of eternity. Yet, when one considers the medley of interacting ideas and other beliefs represented by the whole assembly, there is an order defined in terms of action among both kinds of notions treated as principles by the user, either ideas or substitutes for ideas, or a combination of both.

Ask: What is the meaning of Raphael’s resort to such a portrayal of a simultaneity of eternity? Is it not the case, that that painting corresponds to the way in which a well-educated student’s mind, even a graduate of a decent sort of secondary education, sees such figures from that period of history? His mind is a simultaneity of eternity, but there is also an ordering, in the sense of sequences, among the elements of that otherwise timeless eternity.

In other words, by introducing the notion of change as such, in the form of continuing, superseding generation of ideas, the time during which the changes unfold is collapsed into a relatively very short lapse of time within the bounds of what is otherwise a simultaneity of eternity.”

And with those wise words of LaRouche in mind, let us begin on our journey. So first, let’s stand back for a minute and look at the painting as a whole. The painting itself seems to be divided into three areas:

– those figures in the foreground at the bottom of the stairs,

– those figures in the background at the top of the stairs,

– and lastly, the top half of the painting, where we see the sky and the clouds, and also the columns and arches of the building in which this whole scene takes place, and it’s done in this way so that everyone fits into this one picture.

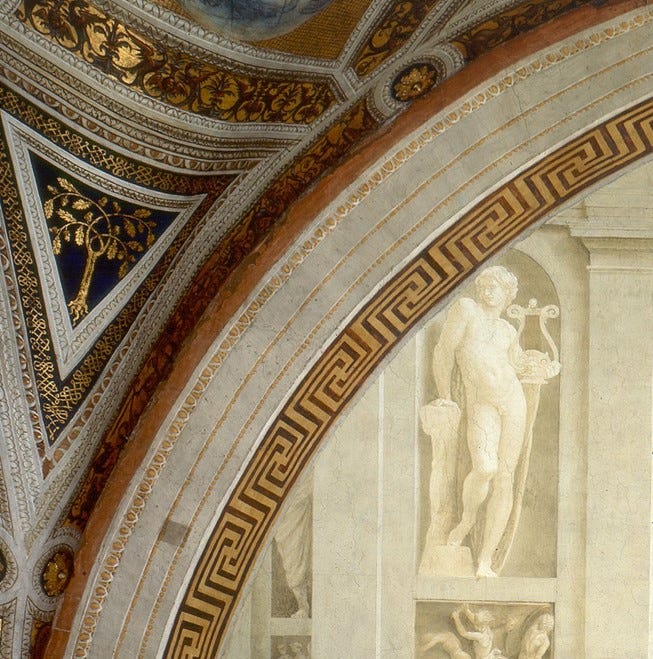

At first glance it would seem that there is no one in this top half of the painting; but, on second glance, it would appear that there are two persons – the two statues.

On the right wall is a statue of someone holding in one hand a spear and with the other hand a shield;

and on the left wall is a statue of someone who is leaning on one arm and in the other arm is holding a stringed musical instrument.

Perhaps, this could be Athena and Hephaestus, as told to Solon by the priest of the city of Sais in Egypt, from Plato’s ‘Timaeus’ dialogue:

Athena, the Goddess of Athens – “that goddess who is allotted the guardianship both of your city and ours, and by whom they have been educated and founded: yours, indeed, by a priority to ours of a thousand years”

and Hephaestus, from whom the Athenians are descended – “receiving the seed of your race from Hephaestus and the Earth”.

From Plato’s ‘Critias’ dialogue, we read that:

“thus diverse gods received diverse districts as their portions and reigned over them. But Hephaestus and Athena, as they had one nature, being brother and sister by the same father, and at one, moreover, in their love of wisdom and artistry, so also obtained one lot in common, this our land, to be a home meet for prowess and understanding”

“the figure and image of the goddess, whom they of old set up in armor, according to the custom of their time, when exercise of war were common to woman and man alike.”

This reference to Athena dressed in armor should be especially read today, to address the important issue of equality for women in the world!

Then, from Plato’s ‘Laws’ dialogue, we read that:

“the class of artificers whose crafts have equipped us for the daily needs of life will be under the patronage of Hephaestus and Athena”.

And, from Plato’s ‘Protagoras’ dialogue, we read that:

“Prometheus therefore, being at a loss to provide any means of salvation for man, stole from Hephaestus and Athena the gift of skill in the arts, together with fire and bestowed it on man.”

What was this gift to man from Prometheus – ‘of skill in the arts’? Perhaps, we shall find out in the course of studying this painting.

Now, after finding those first two figures in the painting, Athena and Hephaestus, let us continue on our journey. And perhaps in looking for a way, of proceeding from the upper area of the two Athenian gods to the lower area containing the Greek philosophers, so too in our story, we’ll imagine that like these Greek philosophers, we are trying to move from the world of Hesiod and Homer that explained the world by the actions of the gods, to a world of philosophy that could explain the actions in the world.

We need to find a way to enter this lower area of the painting, and so let’s look for an opening or an entrance.

In the foreground, at the far left of the painting, where the painting seems to be missing a small corner (because of an actual door that enters the room) we see a man reading a book that is placed on top of a pillar, where a statue, or something might have been placed. And, while all the other persons in the painting seem to be grouped as if in a discussion, this person is set off alone, by this entrance to the room and he’s facing outward towards us, the viewers, who are entering the room, as if he is addressing us about the painting.

While very little knowledge has been preserved concerning the philosophers of Athens, there is one book that has somehow managed to survive the passage of time – ‘The Lives of Eminent Philosophers’ by Diogenes Laertius. Although it contains more gossip and trivia on the philosophers than on their actual ideas, and although it divides the philosophers into strange categories or schools, nonetheless, it has become a primary source for our attempts to know the lives of the Greek philosophers. And so, I think that this person could be Diogenes Laertius.

And there are three other persons besides him - to the left are two persons, one very young and one very old, and behind him is one whose hands are on his shoulders.

And so perhaps, this is Diogenes, along with many others – some whose works are partly found and some that are lost, some old and ancient and some new and modern, and some who simply gave a helping hand along the way – as if they are all, opening up this book for us to read.

[Note: A translation of this book was made by Ambrogio Traversi in Florence in 1433 and was widely circulated.]

It’s as if Diogenes is our Maitre D’, welcoming us into this dialogue of our journey.

Next, we will begin to look at those other figures in the left foreground, where we see different people writing and copying something, or showing and watching something.

[next week - part 2 - the Pre-Socratic Philosophers]