This is a presentation that I gave for the Rising Tide Foundation, on re-discovering the ‘Odyssey’ of Homer - Was it History or was it a Myth ?

The presentation is about an hour and a half, and there’s another half hour of Q & A. You may watch the video, and/or you may read the full transcript with images to this lecture.

Re-discovering the ‘Odyssey’ of Homer. Was it History or a Myth ?

by Gerald Therrien

One way of looking at Homer is shown by Rembrandt’s painting of ‘Virgil contemplating the bust of Homer’ – Virgil vainly trying to figure out how Homer was able to compose his poem. Rembrandt has the light shining on the bust of Homer in such a way that it looks like the light is instead coming from Homer and shining outward, and he has Virgil placing one hand on Homer’s head while his other hand is holding his nice shiny gold chains. So, Rembrandt contrasts Homer, who is Plato’s Aristocratic man who is motivated by discovery and creativity, against Virgil, who is Plato’s Timocratic man who is motivated by power and by the appearance of honor. Rembrandt so poetically shows this conflict in Virgil with one hand on Homer and the other hand on his gold.

Another way of looking at Homer is seen in a poem by John Keats, ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’.

[Note: George Chapman(1) published the first English translation of Homer.]

‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’ by John Keats

“Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.”

In this poem, Keats writes about his excitement on reading and discovering the wonder of Homer’s Odyssey. Some people believe that Homer’s poems, the ‘Iliad’ and the ‘Odyssey’, were not true history but were simply myths that he concocted, just as Virgil concocted his myth of the ‘Aeneid’(2). But that was until Heinrich Schliemann’s defiant discovery of the ruins of Troy in the 1870’s, changed peoples’ minds and proved that the Iliad and Trojan war did happen. But what about Homer’s other poem, the Odyssey? Was that based on true events, or was it just a myth or a fable? Now, some of you may have read Homer, and some may not have. So, first, who was Homer(3)?

According to Herodotus in his ‘Life of Homer’, Melesigenes (his real name) a teacher at Smyrna, decided to join Mentes, a shipowner, to visit different places – to see the world while he was still young. On one trip on their way back from Spain and Etruria, he became very ill with an eye disease, and was left at Ithaca at the home of Mentor, a friend of Mentes, and while recuperating, he researched and learned the story of Odysseus. Later, he rejoined Mentes to sail with him, until his eye disease returned, but this time he didn’t recover and became blind.

[In the Odyssey, Homer repays his friends by having Athena take the guise of Mentes (book 1) and take the guise of Mentor (book 2) – so he’s already changing history a little bit!]

Melesigenes returned home to Smyrna and decided to try his hand at poetry. Later, he decided to go to Cyme and asked the city, if they supported him at public expense that he would bring great glory to their city. However they decided that if they would support all of the ‘homeroi’ [what the Cymaeans called the blind] then the city would have a large and useless multitude. That name, ‘homeroi’, stuck with Melesigenes, and from then on, he was called ‘Homer’. He travelled and performed his verses in salons in different cities, and eventually he arrived in Chios and there set up a school, settled down, married, had two daughters, and it is here that he most likely composed the Iliad and Odyssey.

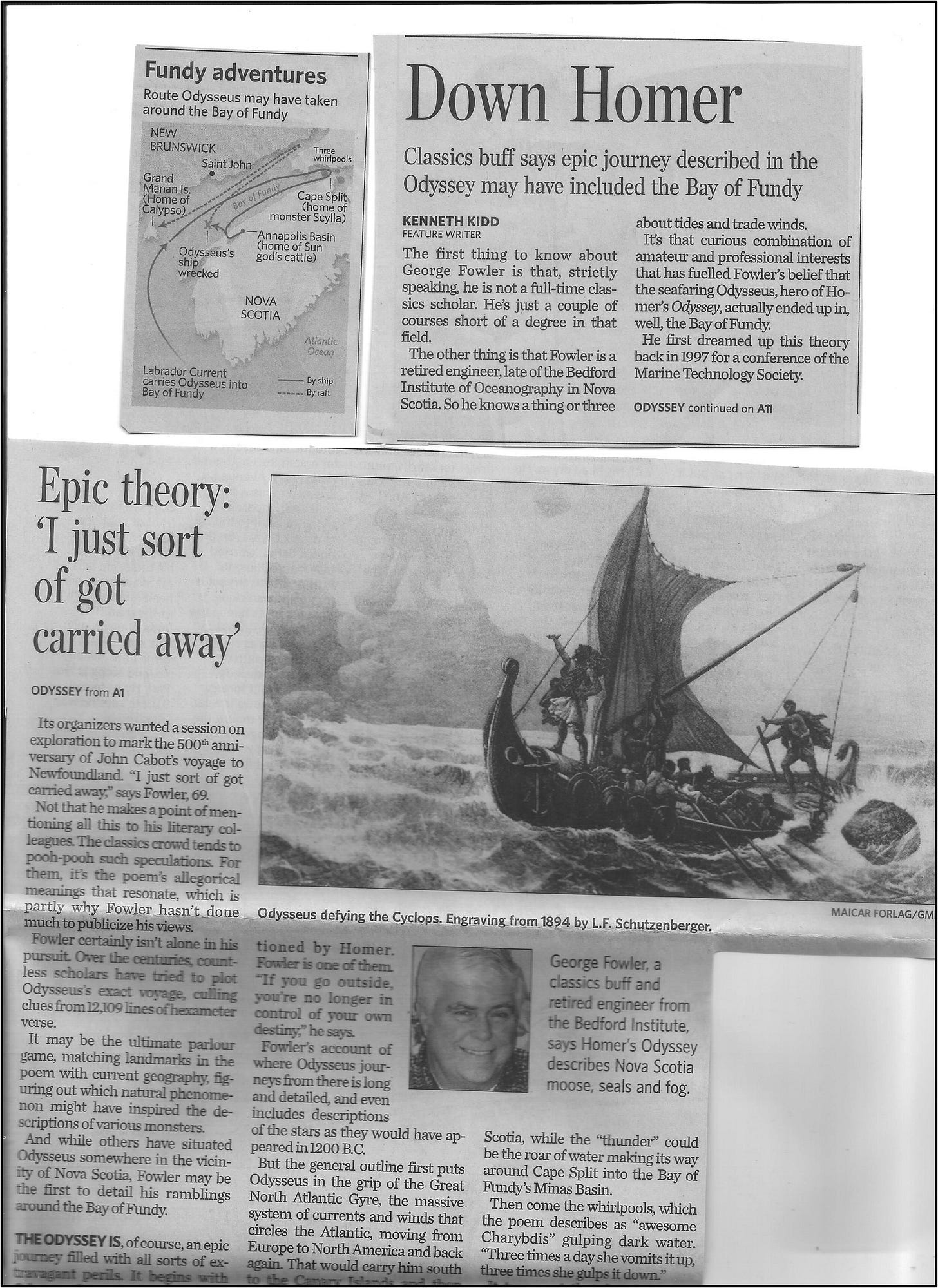

Some people believe that in the Odyssey, Odysseus merely wandered around the Aegean Sea, close to home, while some people believe that he sailed to Canada.

[from the Toronto Star, May 26, 2010]

Here is a newspaper clipping of a retired engineer from Nova Scotia [George Fowler] who had the idea that the tides and whirlpools found at the Bay of Fundy describe Charybdis in Homer’s Odyssey. It’s interesting and it opens up possibilities to think about. But, did Homer know about the Americas? Plato talks about the American continent in his ‘Timaeus’. What did Homer know about the world? Had he known of maps showing the extent of the world? For more about this, if people haven’t already seen it, they should watch Stephen Doyle’s lecture on ‘The Importance of Hapgood’s Map of the Ancient Sea Kings and Why the Study of Ancient History Must be Reformed’.

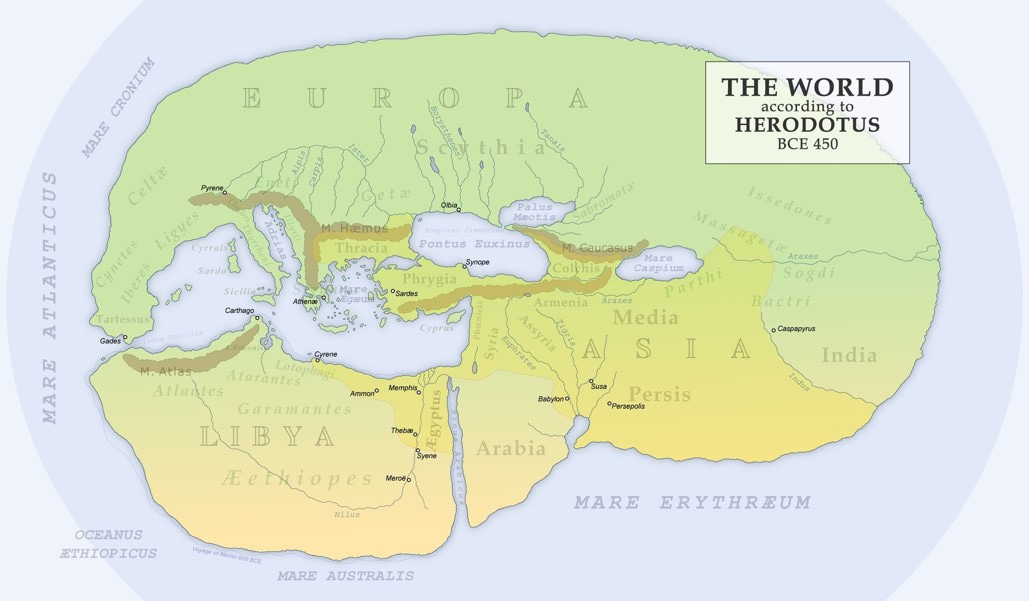

Let’s look at one possible representation of a map of the Mediterranean world and try to imagine the different parts of Asia, Europe, and Africa, as they may have appeared at the time of Homer.

First – Asia. According to Herodotus (who lived 485 – 425 BC), Asia began south of the Caucasus mountains along the eastern shore of the Euxine Sea (Black Sea) and encompassed Anatolia (that contained 30 nations), Phoenicia, Syria, and Palestine as far as Egypt; and then along the Erythraean Sea (the Red Sea or Arabian Gulph, and the Indian Ocean) it encompassed Arabia, Assyria and Persia as far as India – and for Herodotus ‘beyond which country, eastward, all is desert, the extent of which is known to no man’.

Second – Europe. According to Herodotus, Europe reached ‘as far as both Asia and Libya’ and began north of the Caucasus mountains [hence we use the weird term Caucasian] along the western shore of the Black Sea, encompassed Greece and extended westward as far as the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar), but for Herodotus ‘no one has discovered whether, on the north and on the east, it is surrounded by the sea’.

[Diodorus Siculus (circa 1st century BC)]

However, there were stories about Jason and the Argonauts, and according to Diodorus Siculus, who lived in the 1st century BC (a contemporary of Cicero), in his ‘History’, he wrote this:

“Not a few, both of the ancient historians and of the later ones as well … say that the Argonauts, after the seizure of the fleece, learning that the mouth of the Pontus [Black sea] had already been blockaded by the fleet of Aeetes, performed an amazing exploit which is worthy of mention. They sailed, that is to say, up the Tanais river [Don river] as far as its sources, and at a certain place they hauled the ship overland, and following in turn another river which flows into the ocean they sailed down it to the sea; then they made their course from the north to the west, keeping the land on the left, and when they had arrived near Gadeira [Cadiz] they sailed into our sea [Mediterranean sea]”

[from the ‘History’ by Diodorus Siculus – Book 4, section 56]

If we believe that the story of Jason and the Argonauts contained a certain amount of historical truth to its story, then we would think that Jason had circumnavigated Europe!

Third – Libya [we know it today as Africa]. Libya began at the Nile river in Egypt, and encompassed all those lands along the Northern sea [Mediterranean Sea] as far as the Pillars of Hercules [Gibraltar] and beyond, AND then along the Southern sea back up to Egypt! The Southern sea would indicate a knowledge of the entire continent of Libya. How did Herodotus know that Libya was circum-navigable?

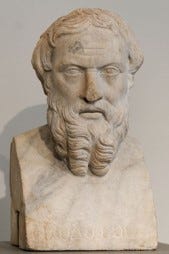

[Herodotus (485 – 425 BC)]

In his ‘History’, Herodotus tells the story of king Nekho, who ruled Egypt 610 – 595 BC, and who had started to build a canal from the Nile river to the Red Sea, but he stopped (because of an oracle) and instead he constructed some galleys, some for the Northern [Mediterranean] Sea and some for the Southern [Red] Sea – and these southern ships he sent to circumnavigate Libya! Herodotus wrote this:

“Libya declares itself to be circumnavigable, except where it is bounded by Asia. The first person known to have proved this, was Necho, king of Egypt. When he ceased to carry on the canal leading from the Nile to the Arabian Gulph, he sent out some Phoenicians, instructing them to sail round by the Pillars of Hercules to the Northern sea and so return to Egypt. These Phoenicians therefore, parting from the Erythraean Sea, navigated the southern sea. When autumn arrived, they drew to shore on that part of Libya opposite to which they might be: there they sowed the ground, and awaited the harvest, which, when they had reaped, they again set sail. Thus they continued their progress during two years: in the third, doubling the Pillars of Hercules, they arrived in Egypt. These persons affirmed, what to me seems incredible, though it may not to another – that, as they sailed round Libya, they had the sun [rising] on the right hand. In this way was Libya made known.”

[from the ‘History’, by Herodotus – Book 4, section 42]

So if we believe Herodotus about King Nekho, then they did it, and it took them three years. Now, Nekho doesn’t seem to be the type of ruler, who would just, all of a sudden, send ships to sail around Libya into the great unknown, hoping to eventually return to Egypt, unless it was already known that it was possible. I say this because a similar project that was started by Henry the Navigator of Portugal in 1415, took over 80 years before Da Gamma sailed from Portugal around Africa and reached India in 1498. This was like an ‘Apollo Project’ of its day that also had led to Columbus re-discovering the route to the Americas in 1492.

Perhaps, it had been possible for Homer to have heard some tales or stories about these voyages of discovery, and for the Odyssey to contain some of these tales of discovery. Perhaps, it may be possible that it was just a tale, that it was meant to show us the change in character that Odysseus needed, to lead such a voyage of discovery? Or, as I will try to show – that it’s both, and is like the way that Strabo views Homer.

[Strabo (64 BC – 24 AD)]

According to Strabo (who lived 64 BC – 24 AD), in his ‘Geography’ he writes this:

“Thus it is that our poet, though he sometimes employs fiction for the purposes of instruction, always gives the preference to truth; he makes use of what is false, merely tolerating it in order the more easily to lead and govern the multitude. As a man ‘binds with a golden verge bright silver’, so Homer, heightening by fiction actual occurrences, adorns and embellishes his subject; but his end is always the same as that of the historian, who relates nothing but facts. In this manner he undertook the narration of the Trojan war, gilding it with the beauties of fancy and the wanderings of Odysseus; but we shall never find Homer inventing an empty fable apart from the inculcation of truth.”

[from the ‘Geography’, by Strabo – Book 1, chapter 2, section 9]

One example (my favorite example), instead of saying ‘the next morning’, Homer would say ‘and then came rosy-fingered Dawn’, and he says this so many times in the Odyssey – ‘the rosy-fingered Dawn’, so he uses fancy, he uses imagination, to draw a picture of something beautiful for our mind, our imagination, to think about.

So now, we’re going to look at Homer’s Odyssey the way that Strabo says: that Homer took actual events, heightened them with fiction and gilded them with the beauties of fancy, but never without the stamp of truth.

The Odyssey is really a story within a story. There is the outer story of Odysseus returning home after ten years of the Trojan War and finding his family and home under an invasion and destruction caused by the many suitors who wished to take over his kingdom. Within this is an inner story of another ten years of wanderings of Odysseus trying to reach home. We’re going to look at this inner story of his wanderings – his Odyssey.

[from Troy to Ismaros]

At the end of the war, Odysseus, his men and 12 ships finally left Troy, and travelled to Ismaros, where they sacked the town, killed its men, took their wives and possessions, and divided the loot equally among themselves. The people, the Cicones, called together all their neighbours and the next morning attacked Odysseus and his men, and forced them to flee. Following ten years of a devastating war, the first thing that Odysseus and his men do, on their return home, is to sack and pillage a town! What is wrong with these people, you ask? Hadn’t they learned anything about war? Or, after 10 years of war, they might think that the world is motivated by power. Homer is showing us how Odysseus and his companions were thinking, at the start of the Odyssey. And because of their actions, their destinies would be punished by ‘an evil fate of Zeus’. But before we blame all this on Zeus, let’s hear what Zeus has to say about it. At a meeting of the gods Zeus said this:

“Well now, how indeed mortal men do blame the gods!

They say it is from us evils come, yet they themselves

By their own recklessness have pains beyond their lot.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook(4)]

So, perhaps, instead of being a punishment, Zeus was steering them onto a path for changing their way of thinking.

[from Ismaros to the land of the Lotus-Eaters]

Zeus raised a ‘North Wind’ and an ‘immense storm’ against them, and, as they were rounding Malea, the southern-most point of Greece, they were driven by destructive winds, away from their return to Ithaca, and after nine days, they reached the land of the ‘Lotus-eaters’. We can assume that the Lotus-Eaters lived along the coast of Libya, because according to Herodotus, in describing all the inhabitants along the coast of Libya, he wrote this:

‘… the projecting coast in front of the Gindanes is possessed by the Lotophages, who (as their name indicates) subsist upon the fruit of the lotus: this fruit is nearly equal in size to that of the mastic, and in sweetness resembles the date. The Lotophages prepare a wine from it …’

[from the ‘History’ by Herodotus - Book 4, section 9]

[Note: The Greek colony of Cyrene, on the coast of Libya, was founded in 631 BC (200-300 years after Homer).]

After landing, Odysseus sent three of his companions to find out who these people were. The Lotus-eaters gave the three men some lotus fruit to eat. But when they ate the lotus fruit, they didn’t want to bring back any word to Odysseus, but just wanted to stay there and eat the lotus fruit, nor to even think of their return to Ithaca. Odysseus had to force his three weeping companions back to the ship, dragging and binding them under the benches, and then he called the rest of his men back to the ship, in case someone else ate the lotus fruit and forgot about returning. They fled from the Lotus-eaters and sailed away – to reach the land of the Cyclopes.

[from the land of the Lotus-eaters to the land of the Cyclopes]

We can assume that the Cyclopes lived in Sicily, and that Odysseus had sailed across the Strait, from the land of the Lotus Eaters, to the land of the one-eyed Cyclopes near the great (one-eyed) volcano at Mount Etna in Sicily, because according to Thucydides (who lived 460 – 400 BC, a contemporary of Socrates), in Book 4 of his book ‘The Peloponnesian War’, where he is discussing the expedition of the Athenians against Sicily, he wrote this:

[Thucydides (460 – 400 BC)]

“… the Cyclops and Lestrigons are said to be the most ancient inhabitants of some part of this country; but, from what stock they were derived, or from whence they came hither, or what is become of them since, I have nothing to relate. Poetical amusements must here suffice, or such information as every man picks up for his own use …”

[from ‘Peloponnesian War’ by Thucydides - Book 4[

[Note: The Greek colony of Syracuse would be founded in 733 BC (100-200 years after Homer).]

The Cyclops were an uncivilized people who ‘do not sow plants with their hands and do not plow but everything grows for them unplowed and unsown … they have neither assemblies for holding council nor laws’. After landing, Odysseus took twelve of his companions with him, and went to inquire about the inhabitants to see ‘whether they are proud and savage and without justice or are friendly to strangers, and have a god-fearing mind’. They found and entered the unattended cave of Polyphemos, the giant Cyclops, and son of Poseidon. While his men wished to take away some of the cheeses and sheep back to the ship and then to sail away, Odysseus wished instead to stay and receive a gift from him – since it was the custom at that time for hosts to give gifts to the guests. But the pitiless Polyphemos trapped them in his cave and devoured six of them before Odysseus devised a plan to blind the eye of the Cyclops and to hide under the bellies of the sheep, and make their escape back to their ships. After finally escaping from the Cyclopes, Odysseus and his companions sailed to the island of Aeolia.

[from the land of the Cyclops to Aeolia]

We can assume that Aeolia was one of the volcanic islands of Lipari lying off Sicily’s north-eastern coast, and that Odysseus had sailed from the land of the Cyclopes, around the coast of Sicily, to the island of Aeolia. According to Strabo, in his book ‘Geography’, he wrote this:

“… Homer's narrative is founded on history. He tells us that king Æolus governed the Lipari Islands, that around Mount Ætna and Leontini dwelt the Cyclopæ, and certain Læstrygonians inhospitable to strangers …”

[from ‘Geography’ by Strabo, Book 1, chapter 2, section 9]

[Note: The Greek colony at Lipara would be founded in 580 BC (200-300 years after Homer).]

Odysseus and his men stayed there with king Aeolos, the lord of the winds, for a month as guests before seeking to leave. To help them, Aeolos gave Odysseus an ox-hide, inside of which he had bound up all the blustering winds, so that they would not blow at all, and then he sent a gentle breeze to carry them and their ships home, and after ten days, they could finally see their homeland. But, because of the foolishness and greed of the men who wanted to see how much gold and silver Aeolas had given to Odysseus, while Odysseus was asleep they opened the ox-hide, all the winds rushed out and a storm then carried them all the way back to Aeolia. The men do not seem to have learned anything or to have changed at all, since their actions at Ismaros when Zeus sent the North Wind to change their destiny. Back at Aeolia, Aeolos would not help them since they thought that they must be ‘despised by the gods’, and he sent them away. And they sailed to the land of the giant Lestrygonians.

[from Aeolia to the land of the Lestrygonians]

We can assume that the Lestrygonians lived on Sardinia, and that Odysseus had sailed from Aeolia, one of the Lipari islands, to the land of the Lestrygonians, on Sardinia, because of the Nuragic statues.

Some historians relate that the legend of the giants may be the result of the Greek sightings of the ancient stone sculptures of the Nuragic culture, like these found at Monte Prama at Sardinia – some of them 8 feet tall.

[Nuragic stone sculptures found at Mont’e Prama, Sardinia – 44 statues have been found.]

Leaving Aeolia, Odysseus and his companions sailed for six days until they arrived at the land of the giant Lestrygonians. Odysseus sent three men to see who lived here, and they found the glorious hall of the king, who was not happy to see them however, but was planning a woeful destruction for them, and then the king snatched one of them and made a meal of him, as the other two rushed back to the ships. But the two men were followed by the giants who attacked all the men and all their ships, of which Homer said this:

“… Thousands of them, like giants and not like men.

From the cliffs they threw boulders the size of a man’s load,

And at once an evil din rose up among the ships

Of men being destroyed and ships being crushed together.

Spearing the men like fish, they bore off their gruesome meal …”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Only Odysseus and his lone ship’s companions were able to escape the destruction, since they had tied up their ship outside of the harbour, but all the other men and the other ships were lost. After fleeing from the giants, Odysseus’ ship landed at the island of Aiaia, the home of the goddess Circe.

[from the land of the giants to Aiaia]

We can assume that Aiaia is the isle of Elba, because according to Apollonius(5) (who lived 295 – 215 BC) in his poem ‘Argonautica’, Jason landed first at Aethalia and then at Aiaia, and he wrote this:

Apollonius Rhodius (295 – 215 BC)

“So they sailed through the river’s midmost mouth [Gibraltar] and came unto ‘the line of islands’ ... After leaving ‘the line of islands’ they sailed to the isle of Aethalia … Quickly they sailed thence across the ocean swell with their eyes upon the Tyrsenian [Etruscan] cliffs of Ausonia, and came unto the famous harbour of Aeaea … There they found Circe washing her head in the sea-water …”

[from ‘Argonautica’ by Apollonius, Book 4]

After Jason had circum-navigated Europe and entered the Mediterranean sea, he sailed past the ‘line of islands’ to Aethalia that we assume to be Corsica, and then towards the Etruscan shore to Aiaia that we assume to be Elba.

[Note: The Greek colony of Alalia was founded in 565 BC (200-300 years after Homer). The Greek colony of Massalia (Marseille) was founded in 600 BC (200-300 years after Homer).]

Odysseus’ men, remembering the Cyclops and the giant Lestrygonians, were fearful of searching the island for any inhabitants. After drawing lots, Eurylochus led forth twenty-two men and they found the hall of Circe, who invited the men into her hall to eat and drink, but she stirred a drug into their food, that turned them into swine. With the help of Hermes, who made him immune to Circe’s drugs, Odysseus was able to free his companions, and they were turned back into men and invited back into her hall to eat and drink (but without any drugs this time) – “until you have taken the spirit into your breast again, as it was when you first left your fatherland”. They stayed for a whole year until they finally wished to return home. When Odysseus asked Circe to show them how to return, Circe wouldn’t tell him how, but she said that they must enter Hades – where our souls go after we die, and to ask this of the soul of Tiresias, the blind prophet who possessed the gift of ‘Foresight’ – not that of predicting the future from a crystal ball but that of foreseeing where the course of events will lead.

[Note: The ‘blind’ poet Homer was showing Odysseus how must seek the advice of the ‘blind’ prophet Tiresias.]

Circe gave instructions to Odysseus about how to prepare a sacrifice for the dead, and how to journey to Hades – don’t worry about a guide, stretch out your sails and let the ‘North Wind’ bring you there – remember how Homer earlier had used this metaphor of the ‘North Wind’ sent by Zeus, that had started Odysseus on his voyage. After arriving at Hades, Odysseus followed the instructions of Circe, prepared a sacrifice and met the soul of Tiresias, who told Odysseus that, first, he will have a disastrous return because of Poseidon:

“… I do not think

You will elude the earth-shaker; against you he has laid up a grudge,

In his heart, enraged that you blinded his beloved son.

You may get there yet, even so, though you suffer ills;

If you are willing to check your spirit and your companions’ …”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Tiresias forecast that IF you check your spirits that you MIGHT get home. Secondly, he spoke of the sheep and cattle of Hyperion, the god of the sun:

“If you let them go unmolested and think of your return

You may yet get to Ithaca, though you do suffer ills.

If you molest them, then I prophesy destruction

For your ship and companions …”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Tiresias forecast that IF you leave Hyperion’s animals unmolested that you MIGHT reach home. Thirdly, he spoke of making a sacrifice to Poseidon:

“… and carry out fine sacrifices to Lord Poseidon,

A ram, a bull, and a boar, the mounter of sows.

Then go back home and sacrifice sacred hecatombs

To the immortal gods who possess broad heaven,

To all of them in order.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Tiresias forecast that IF you finally do reach home, how you would offer a sacrifice to Poseidon and the gods. Tiresias then showed Odysseus how he could speak with other souls of the dead. Odysseus met the soul of his mother, Anticleia, and spoke about his family. Odysseus next met the soul of Agamemnon, who told him of how he was killed by his ‘cursed wife’ and he asked if Odysseus had any news of his son, but Odysseus had none. Odysseus then met the soul of Achilles who asked about his son, and Odysseus spoke of his son’s courage at Troy.

Odysseus also saw the ‘difficult pains’ of three other souls – of Tityos, who was being punished by having his liver eaten by two vultures each day, while it grew back each night; and of Tantalos, who was being punished by standing in a lake beneath fruit trees, but the lake would dry up when he tried to drink, and the wind would blow away the fruit whenever he tried to pick any; and of Sisyphos, who was punished by rolling a monstrous stone to the crest of a hill, before it would roll back down, only to have to push it back up again. Then not wanting to stay any longer, he called his men back to his ship and they sailed away from Hades.

Perhaps, the idea of having to go to Hades, is to reminisce with those who have died – those who were relatives or dear friends or companions – in making your fateful decisions; or to see the punishments of others who did not have good intentions in their fateful decisions. But Odysseus didn’t talk to them – his ‘bold spirit’ talked to their souls. And, perhaps, this metaphor of going to Hades, is trying to indicate that if you wish to discover new worlds, you have to have a bold spirit, to have the courage to be willing to face the great unknown, in order to get there.

So, Odysseus and his companions returned to the island of Aiaia where they rested. Circe took Odysseus aside, away from his companions, and again did not tell Odysseus how to return home, but told him how to escape from the next challenges he was to face – first, the Sirens, and then Scylla and Charybdis.

Odysseus told his companions that Circe had said that they must not listen to the voices of the Sirens, or they’ll become enchanted and stay there in the meadow full of flowers and never leave, until their bodies had rotted away. So Odysseus took softened wax and smeared it into the ears of all his companions, so they would not hear the singing. Odysseus alone was allowed to hear their song, and he ordered his men to bind him, hand and foot, to the mast, so that they’d be able to escape the Sirens. And what was it that the Sirens sang that so enchanted Odysseus?

“Come near, much-praised Odysseus, the Achaians’ great glory;

Bring your ship in, so you may listen to our voice.

No one ever yet sped past this place in a black ship

Before he listened to the honey-toned voice from our mouths,

And then he went off delighted and knowing more things.

For we know all the many things that in broad Troy

The Argives and the Trojans suffered at the will of the gods.

We know all that comes to be on the much-nourishing earth.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

The Sirens tempted him with flattery and sang that they could predict his future (unlike the forecast of Tiresias), but Odysseus, being tied up, was able to ‘check his spirit’ and his companions, unable to hear them, were able to sail past the Sirens towards Scylla and Charybdis.

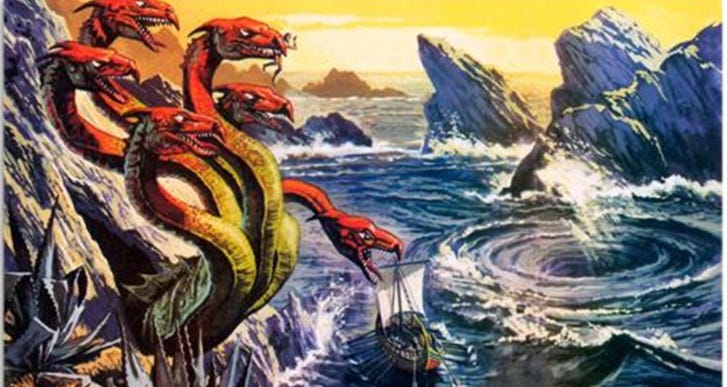

Circe had told Odysseus that if his companions got past the Sirens, that at that point she couldn’t tell him which of two ways he should take – he, himself, must decide ‘in his heart’. One way was by the Wandering Rocks, where all other ships were destroyed by sea waves and storms of destructive fire. The other way was by two crags – Scylla and Charybdis. On the first crag lives Scylla, who has six very long necks, each one with a terrible head, each head having three rows of teeth, and from every ship that tries to pass, she will snatch a mortal from that passing ship with each of her six heads. On the second crag lives Charybdis, who three times a day will suck back the water terribly and three times a day will send it back – but if you are there when she sucks the water up or sends it back, nothing could save you from evil.

Circe told him to sail by the crag of Scylla – ‘since it is better by far to miss six companions, than all at once’. Odysseus urged his men to row hard against the waves and he urged the pilot to steer towards the crag of Scylla (but he didn’t tell them any more – fearing that if he did, in their fear of what would happen, they’d cease rowing). They were able to escape past the two crags, but were helpless as Scylla snatched away and ate six of the men – ‘the most piteous thing I saw with my eyes of all that I suffered as I sought out the paths of the sea’, and they sailed to the island of Thrinacria, where the god Hyperion kept his beautiful herds of cattle and flocks of sheep.

[from Aiaia, past Scylla and Charybdis, to Thrinacria]

Metaphorically, sailing past the Sirens, and Scylla and Charybdis was like venturing out into the vast unknown. If we assume that sailing past the Sirens, and Scylla and Charybdis was sailing past the Pillars of Hercules, then Odysseus must have sailed out into the Atlantic ocean. I drew this part of the journey with a dotted line because this is where there is so much controversy, as some people refuse to admit that Odysseus could have sailed out into the ocean. But in the ‘Life of Homer’, Herodotus wrote that young Homer had sailed to Spain. And we saw how Jason had circum-navigated Europe and King Nekho had circum-navigated Africa past the Pillars of Hercules. According to an Arabic explorer who landed on an island in the Atlantic near Morocco that was inhabited by wild sheep, he warned that they were not good to eat! Remembering that Tiresias had warned Odysseus not to eat any of Hyperion’s cattle or sheep, we may assume that Thrinacria is one of the Madeira islands.

As they were near Thrinacria, Odysseus remembered the warning he received from Tiresias, and he told his companions that a terrible evil would happen to them there, and he wanted to sail on past the island. But his companions said they were worn out with fatigue and sleepiness, and were afraid that a storm might come up during the night and destroy the ship, and that they therefore wanted to stay only one night on the island and then to leave in the morning. Odysseus agreed but made them swear an oath not to slaughter any of the cows or sheep. But that night a storm arose and the wind blew steadily for a whole month, keeping them on the island, until their provisions from the ship were all gone. While Odysseus was gone away from his companions, to pray to the gods to show him the way to leave and return home, the men unfolded a bad plan – to kill some of Hyperion’s cattle:

“There are all kinds of hateful deaths for wretched mortals,

But most piteous is to die and meet one’s fate by hunger …

But if he is at all enraged for his straight-horned-cattle

And wishes to destroy the ship, and the other gods follow,

I would rather gasp once into a wave and lose my life,

Then to be starved a long time on a desert island.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Not trying to come up with some kind of a way out, the men listened to their despair, instead of relying on hope and they made that bad decision – they slaughtered the cattle, both to make a sacrifice, and to prepare a meal – all to Odysseus’ horror when he returned. When the storm finally ceased, they boarded the ship and fled Thrinacria.

The story of Thrinacria unfortunately shows that Odysseus never reached America, never reached Nova Scotia (sorry to our Canadian friends). If you read the ‘Life of Christopher Columbus’ by Washington Irving, how Columbus kept two sets of books, one true set for himself alone, and another false set that he used to show his men that they weren’t about to sail off the edge of the flat earth, it shows that while dealing with the problems of wind, weather and provisions, the hardest part of the voyage in crossing the Atlantic ocean was controlling the spirit of his men – the same problems faced by Odysseus at Thrinacria. Odysseus’ men showed that they weren’t capable of a trans-Atlantic voyage.

[this isn’t to say that there wasn’t trans-Atlantic commerce(6), but just not by Odysseus.]

After they fled from the island, Zeus sent the shrieking West Wind in a raging tempest and threw a thunderbolt at the ship. The ship whirled around and filled with brimstone and sank, as all of Odysseus’s men were thrown from the ship into the waves – ‘they lost their own lives because of their recklessness’. Only Odysseus, who wasn’t part of the decision of despair, was able to survive, by holding on to part of the keel of the wrecked ship as he was carried away by the wind.

[from Thrinacria to Ogygia]

After being borne on the waves for ten days he was brought to Ogygia, ‘the flood-circled island where the navel of the sea is’, and where lived the goddess Calypso, daughter of Atlas. If Ogygia was 10 days from Thrinacria (Madeira), we may assume that Ogygia was one of the Azores islands.

The inset shows that, interestingly, the Azores Plateau lies at the triple junction of the North American Plate, the Eurasian Plate, and the African Plate. I’d think that this would cause a lot of volcanic activity and earthquakes. And Homer had called Ogygia ‘the flood-circled island where the naval of the sea is’.

Calypso wished for Odysseus to remain with her on Ogygia, but Odysseus was not persuaded and wished instead to return home, of which Homer says this:

“During the days, sitting up on the rocks and on the beaches,

Shattering his heart with tears and laments and groans,

He kept looking over the barren ocean, shedding tears.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

While Odysseus waited there for seven long years(9), finally at the urging of Athene, Zeus sent his messenger to tell Calypso to allow Odysseus to leave. Calypso instructed Odysseus to build a raft with a mast and sail, and with a rudder to steer straight. And Odysseus, ready to bear whatever should happen to him, replied that:

“Yet even so I am wishing and longing all my days

To go home and to see the day of my return.

And if one of the gods wrecks me on the wine-faced sea,

I shall bear it in my breast, with a long-grieving heart.

For I have suffered much already and endured much,

On the waves and in war; and let this be added to those.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

This is different from his companions who said they’d rather die quickly of drowning than slowly of starvation. Unlike his men, Odysseus was still hoping and not despairing, and ready to meet his fate, whatever may happen. So he sailed as Calypso had bid him, watching the Pleiades (that was used to show the start of sailing season), and the Wagon (that was used to find the North Star), and keeping the North Star on his left, he sailed east.

After seventeen days he finally saw Scheria, the land of the Phaeacians, but Poseidon, still angry at Odysseus, stirred up a violent storm against him, breaking the mast and tossing his raft about, as he held on – ‘shunning the end of death’. He was helped by the goddess Leucothea, and after three days, he came ashore at Scheria.

[from Ogygia to Scheria]

If Scheria was 17 days sailing east of Ogygia, then we may assume that Scheria is possibly located in the area on the southern coast of Spain, that Diodorus Siculus(7) writes about in describing the Amazons and the Atlantians. Homer may have described the city of the Phaeacians as an ideal city, a kind of a utopia, but some people assume that the Phaeacians were the descendants of the Atlantians, and so they try to place Atlantis somewhere ‘on the edge of the ocean’, either at southern Spain, or northern Morocco, or at the Azores(8).

Odysseus met the king, Alcinoos, and attended the assembly of the Phaeacians, who are ‘famous for ships … as swift as any wing or thought’, and Alcinoos summoned the singer Demodocos, of which Homer says this:

“The gods have granted him to please beyond others

With whatever kind of song his spirit urges him to sing …

Then a herald came near, leading the trusty singer

Whom the Muse loved dearly and gave both good and ill.

She blinded him in the eyes but gave him a sweet song.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Wait a minute! I think that Homer just placed himself into the story! When Demodocos sang tales of the Trojan war, king Alcinoos saw that this caused Odysseus to cover his head and shed tears, and so he asked Odysseus this:

“Tell me your land and your district and your city

So that ships that are steered by thought(10) may convey you there,

For there exist no pilots among the Phaeacians,

And there are no rudders at all such as others have,

But the ships themselves know the intentions and minds of men.”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Odysseus would tell them who he was and where he was from, and then he would tell them of his journey, from when he had left Troy until he had arrived there. After this, Alcinoos agreed to send him home. While they sailed in one of the Phaeacian ships, Odysseus fell asleep, and when the ship reached Ithaca, they set him down on the shore, while still asleep, with his gifts, and they started back homeward, before he woke up. After returning home, getting rid of the suitors, and reuniting with his family, there was still one more place where Odysseus had to travel to, as he remembered what Tiresias had told him:

“… he ordered me to visit many towns

Of mortals, holding in my hands a well-fitted oar,

Till the time I come unto those who do not know

The sea and do not eat a food that has been mixed with salt,

Or about well-fitted oars that are the wings for ships …

When another wayfarer has confronted me

And said I had a winnowing fan on my gleaming shoulder,

He bade me to fix my oar then into the earth

And offer fine sacrifices to lord Poseidon …”

[from Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Albert Cook]

Now, when I thought of this scene, it really became most important, because if Odysseus followed this final advice from Tiresias, then those people that he found, far away and land locked, would ask him ‘what is that oar?’ And Odysseus would have to explain about ships, and about sailing and travelling to other parts of the world, and also about how the world really was. And then they would ask him why – what is the reason for your travelling? And Odysseus would tell them, well … take a seat … do I have a story to tell you – a story about an ‘Odyssey’.

Homer was showing us that it’s not enough to make a discovery, but that it has to be explained or taught, that it has to be passed on to others. And we can see how Homer changes Odysseus – from steering his ship, to learning how to steer his thoughts. And that this is the real purpose of colonization – not subjugating populations to become part of an empire, but sharing in the discoveries of human civilization.

[Greek colonization – 8th to 6th centuries BC[

It has been said that the ancient Greeks would teach their children to read, to recite and to memorize Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey’. What would be the effect on the minds of their youth in being immersed in Homer’s ideas? A few generations after Homer, the Greeks began a colonization project along the coasts of Libya, Italy and France, – at Cyrene, at Syracuse, at Lipara, at Alalia, at Massalia, and others, I’m just naming those places that I mentioned.

It has been reported that around the time of the Trojan War, that Greek civilization went into a Dark Age – perhaps it was caused by a cultural degeneration or by invasions and wars or by catastrophic natural disasters – but it even resulted in the loss of their writing system. Now, what if that happened to us, what would we do? – become some Mother Earth worshippers, or some believers in magical mysteries, or some anti-science luddites? Or would we try to discover a way to go forward that would lead to a better understanding of the unknown.

[I’m reminded about back when I used to work for Bell Telephone (that was a while ago) and we had this poster on the wall in our lunchroom, that I used to like looking at. It was a cartoon about two cavemen – one was down on all fours, and the other was slowly trying to stand up on two legs. And the caveman down on all fours, looked over at the other one and yelled, ‘Hey! Get back down here, before you hurt yourself!’ I really liked that one.]

While today’s politically-correct oracles of Delphi attack Christopher Columbus as the source of all the evil that befell the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, they fail to mention the brutal, feudal empires of the British, the French, the Portuguese, and especially the Spanish empire, (and their spiritual mother, the Roman Empire), and of their insatiable lust for gold, silver and sugar – and that this idea of empire, the Florentine Renaissance sought to put an end to, with their project of discovery, that Columbus was a part of.

Foolishly, trying to destroy the discoverer will not put an end to the evils of empire, but rather prolong it. Instead we should celebrate the discoverer, as leading the way toward eliminating tyrants and empires among men.

So you know how people say don’t kill the messenger? Perhaps, we should be saying, ‘Don’t Kill the Discoverer!’ – so that we don’t overlook this idea of the individual discoverer – in opposition to the materialist attempts at history, attempts that take the individual’s discovery out of the picture, which is so wrong, because it’s the individual that makes discoveries and it’s the individual that makes history. The individual discoverer isn’t a victim of fate but can decide the direction that he or she goes in, not going with whatever way the wind blows.

But then there’s the North Wind – Homer’s metaphor of the North Wind – that changed Odysseus’ course that began his Odyssey and later steered him to Hades, and whether it led to more troubles or a solution to his troubles. What if Homer hadn’t lost his sight; would he still have turned his talent to poetry; would we still have an Odyssey? I like to think that it wouldn’t have mattered to him. But what if fate gave us an obstacle that blew us off course? Would we act like Odysseus’ companions or instead would we be like Odysseus and let our Muse show us how to ‘steer our thoughts’ to try to effect a new discovery. Homer may be telling us that we shouldn’t take things so literally, so formally, we should rely more on our imagination and on our creativity – to help us find that enthusiasm that we read about in Keats’s poem ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’.

Now, I want to bring back Keats, and read another poem that he wrote as part of a letter to his sister, Fanny, about his walking tour to Scotland to visit the birth-place of Robert Burns, and in the middle of this letter to Fanny, he starts writing a poem about it, off the top of his head. So, this is the last stanza of that:

[slide 50: quote from Keats]

“There was a naughty boy,

And a naughty boy was he,

He ran away to Scotland

The people for to see –

Then he found

That the ground was as hard,

That a yard was as long,

That a song was as merry,

That a cherry was as red,

That lead was as weighty,

That fourscore was as eighty,

That a door was as wooden

As in England –

So he stood in his shoes

And he wondered,

He wondered,

He stood in his shoes

And he wondered.”

[from a letter to Fanny Keats, by John Keats (1818).]

By simply changing one letter – changing an ‘a’ into an ‘o’ – by changing the word ‘wander’ into ‘wonder’ – a voyage of discovery of things, becomes a voyage of discovery of ideas.

I hope that I have been able to show the poetical method of Homer in writing his Odyssey, and as Strabo said, how Homer gilded history with the beauties of fancy, and I think that Keats would agree:

“Ever let the Fancy roam,

Pleasure never is at home:

At a touch sweet Pleasure melteth,

Like to bubbles when rain pelteth;

Then let winged Fancy wander

Through the thought still spread beyond her:

Open wide the mind’s cage-door,

She’ll dart forth, and cloudward soar …”

[from ‘Fancy’, by John Keats]

That’s just the first 8 lines of his poem. I’ll let you read the rest of it on your own – that’s your homework.

Perhaps reading Homer’s ‘Odyssey’ or Apollonius’s ‘Argonautica’ or Washington Irving’s ‘Life of Columbus’ could inspire us to continue to try to discover these ‘beauties of fancy’ that we find in that ‘poem of the universe’. And maybe the next time we see a morning sunrise, we’ll think of Homer and those rosy-fingers of Dawn.

Footnotes:

(1) George Chapman (1559 – 1634) was a good friend of Christopher Marlowe (1564 – 1593/1616) and they were part of a circle of intellectuals, sponsored by Walter Raleigh, that were studying the classic Greek plays in attempting to create an English theatre, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

(2) Virgil, who lived 70 – 19 BC, was commissioned by Caesar Augustus to write an epic that would legitimize the duty and obedience owed to the ‘pax romana’ of the new Roman Empire. Virgil spent over 10 years writing the ‘Aeneid’ when he died in 19 BC – in which he never once mentioned Homer, but he did show how he despised Odysseus, calling him a ‘heartless schemer’, a ‘master-craftsman of crime’ and the ‘double-talking Ulysses’. Unfortunately, Dante never read Homer (the first translation of the Odyssey into Latin wasn’t done until 30 years after Dante’s death), and he had to rely on Virgil and other Latin writers for the story of the life of Odysseus, which is why Dante places Odysseus in the 8th circle of Hell. However, Dante still must have come to understand the problem with Virgil, as he wouldn’t let Virgil enter Paradise – only Purgatory and Hell.

(3) Regarding the age of Homer, Herodotus writes in his History (Book 2.53) ‘For Hesiod and Homer, whom I reckon my elders by not more than four hundred years …’ Since Herodotus lived 485 – 425 BC, that would place Hesiod and Homer sometime after 885 BC. Most people tend to agree with that regarding Hesiod but think that Homer was older. However, in the ‘Life of Homer’ (38) by Herodotus (that some people think was not written by Herodotus, and so name the author, Pseudo-Herodotus), he calculates the birth of Homer from the time of the founding of Smyrna and writes that ‘Homer was born one hundred and sixty-eight years after the Trojan War’. Since Eratosthenes dated the Trojan War to 1194 to 1184 BC, that would place the birth of Homer at 1026 BC. So, Homer could have been born sometime between 1026 and 875 BC, and that would put the writing of the Odyssey at some 350 or 500 years before the birth of Socrates.

(4) Although Homer wrote in unrhymed ‘dactylic hexameter’, George Chapman did his translation in rhymed couplets of ‘iambic pentameter’. While similar translations may be difficult to read because of this, perhaps too much attention is paid to the rhyming and metering, leaving less emphasis on the meaning that Homer had intended. And so, while I was looking over other translations, I found a very good prose translation, whose lines correspond to Homer’s lines, but in a translation without concern for the rhyme or meter, and hopefully, with more concern for Homer’s intention. I’ve used the translation by Albert Spaulding Cook, (who lived from 1925-1998), and who had once taught at Western Reserve University, the same university as Professor Harold Fowler, whose translation of Plato’s ‘Phaedo’ dialogue we read at our Wednesday Evening Reading Club.

(5) Apollonius (295 – 215 BC) was a student of Callimachus (310 – 240 BC) at the Library of Alexandria, and Apollonius later became the head of the Library, before Eratosthenes (280 – 194 BC).

(6) In 1985 at Uluburun, off the southern coast of Turkey, a shipwreck was found, dated to around 1300 BC (which is around the time of the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts) that contained copper of 99% purity. There is only one place on earth where copper of this purity can be found – Isle Royale and the Keweenaw peninsula in northern Michigan on Lake Superior in NORTH AMERICA. Archeological investigations have discovered over 5,000 ancient copper mines, the earliest dated to around 2500 BC (around the time of the construction of the Giza pyramid in Egypt) and the latest dated to around 1200 BC (around the time of the Trojan War) when they suddenly stopped. There must have been trans-oceanic commerce between the Americas and the Mediterranean AT LEAST from 2500 to 1200 BC. Why the commerce stopped may be related among the other causes that led to the development of iron to replace bronze.

(7) According to Diodorus Siculus, in his History (Book 3.56-61), he writes about the people who dwelt in the regions on the edge of the ocean who ‘excelled their neighbors in reverence towards the gods and the humanity they showed in their dealings with strangers, and the gods, they say, were born among them’, and of their first king Uranus, and of the most renowned of his sons, called the Titans, was Atlas who gave the name of Atlantians to his people and whose sons were distinguished for justice to their subjects and love of mankind; and was Cronus who was notorious for his impiety and greed and who was lord of the region of the west – Sicily, Libya and Italy.

(8) In 1882, a few years after Schliemann had uncovered the ruins of Troy, a book was written by Ignatius Donnelly (who lived 1831 – 1901) called ‘Atlantis: the Antedeluvian World’ [i.e. before the flood] that attempted to prove that Plato was telling the truth, that Atlantis once existed at the Azores. And he wrote that all the sagas from different cultures about a great flood were also true. But how did a guy from Minnesota write such an encyclopedic analysis of ancient peoples? Donnelly was born in Philadelphia and graduated from Central High School – studying the curriculum of Alexander Dallas Bache and Rembrandt Peale.

[for more about the part played by Central High School in the industrial development of the United States, read Anton Chaitkin’s ‘Who We Are’.]

Later, Donnelly moved to Minnesota, joined the Republican party, was elected Lt. Governor in 1859 (at 29 years-of-age), and was elected three times to the United States Congress as a Lincoln Republican (1862-1868). Obviously, he made good use of his time at the Library of Congress.

(9) Some people have thought that having to wait so long at Ogygia may have referred to the Atlantic doldrums.

(10) Some people have thought that this ‘spirit of the ship’ may have referred to the use of a magnetic compass to steer the ship.

Some Further Reading

‘Odyssey’, by Homer (circa 975 BC)

‘Argonautica’, by Apollonius Rhodius (circa 250 BC)

‘A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus’, by Washington Irving (1828)

‘Henry the Navigator and the Apollo Project That Launched Columbus’, by Timothy Rush (21st Century Science and Technology, Summer 1992)

‘On Eratosthenes, Maui's Voyage of Discovery, and Reviving the Principle of Discovery Today’ by Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. (21st Century Science and Technology, Spring 1999)

‘Homer's Odyssey, Long-distance Seafaring, and The Principle of Colonization’, by Gabriele Liebig (21st Century Science and Technology, Spring 1999)