In Defence of King Arthur,

by a Canadian Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

Part 6 – The Land of the Faerie Queene

So, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history story of Briton’s hero, King Arthur, there are no lovey-dovey affairs of Guinevere, there are no carpet knights sitting around the round table (or chasing after windmills), and there is no absurd search for the holy grail. Because we were not on a quest for the holy grail, but on a quest for beauty, goodness and truth.

All these romantic chivalric myths were added later to try to mystify the true story of Arthur, and for a different purpose than the intention of Geoffrey – that the deeds of these men should be remembered for all time. And Arthur should be remembered, by Geoffrey’s story and not by the Norman romantic fantasies. Or the recent Hollywood versions either.

But, there’s another way in which Arthur is remembered – in a different way than what one might have imagined.

About 250 years after Geoffrey of Monmouth, we see another Geoffrey – Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote the Canterbury Tales, and in all of his poems and in all of his tales, he only mentions King Arthur once – in the wife of bath’s tale, and only in the first few paragraphs:

“In the olden days of King Arthur,

Of whom Britons speak with great honour,

All this land was filled full with faerie.

The Elf-Queen with her fair company

Danced full oft in many a green mead.

That was the old opinion, as I read –

I speak of many hundred years ago.

But now no man sees elves I know …”

It would seem that not only did Arthur free Briton from the Roman Empire and from the magicians, but he also freed the artists, and the musicians, and the dancers, and the poets. And the land of Briton became a land of mirth and fables, and full with elves and faeries. But when we lose our independence, do we also lose our ability to see this land of faerie?

Because now, no one sees elves anymore (maybe Robert Frost was the last one) – we’ve become literalists and scholastics and nominalists and empiricists – we cannot see the land of faerie anymore, we only are shown the land of escapism, a land that claims to be neither good nor bad (as if such a thing were possible) and it’s not like the escape of a prisoner, but it’s more like the escape of a deserter.

But then, as some story-tellers have said, maybe it was because the fairies and elves spoke to us in the language of old Briton, of old Celtic, and old Welsh, a language that we didn’t understand anymore. And so, they said, the fairies and elves took up this mish-mash of Norman and Saxon utterings and grunts, and they turned it into something they called Anglish - something that we could use to talk to them again. Perhaps.

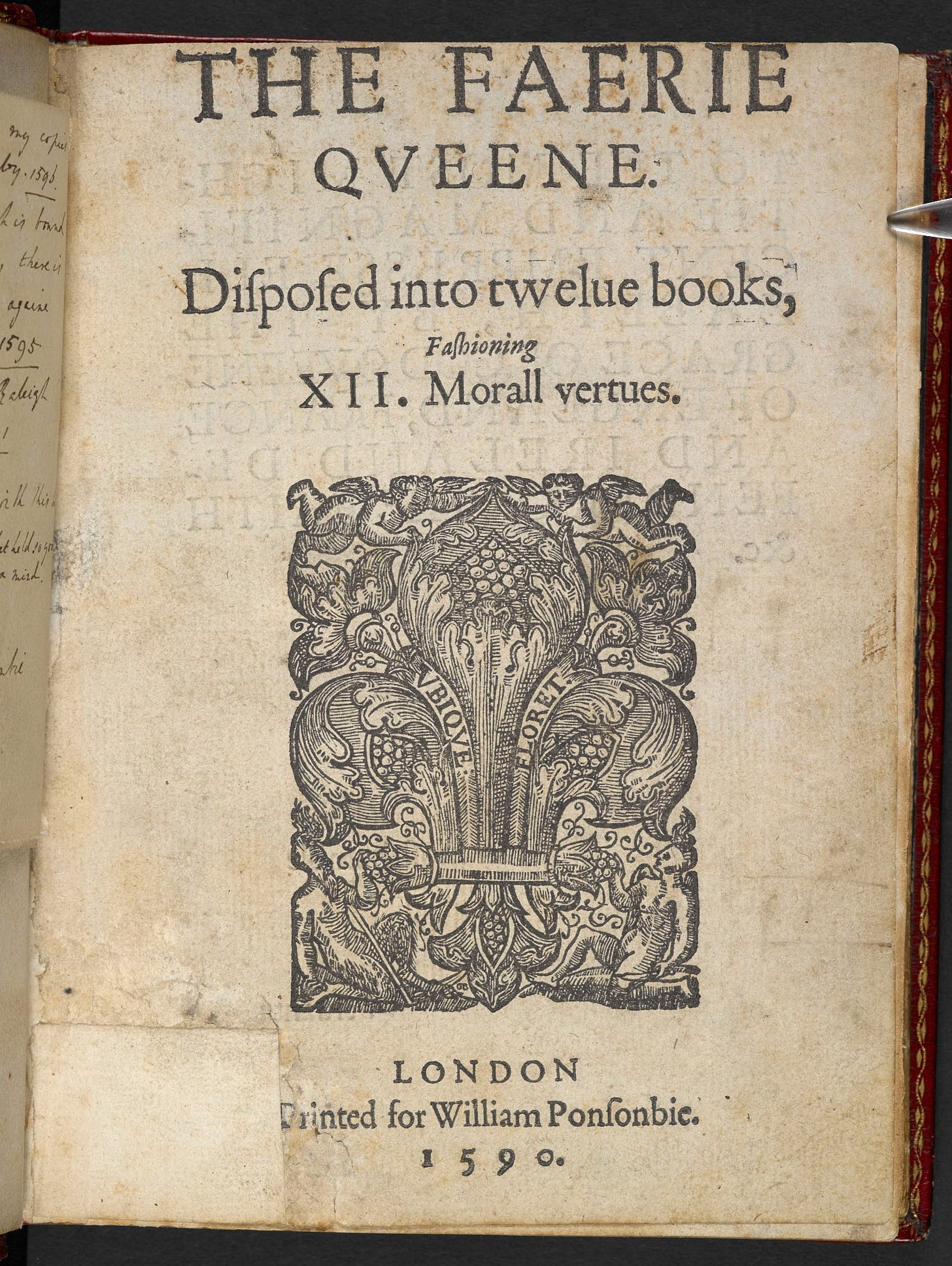

For it seems that 200 years after Chaucer, we see this land reappear in Edmund Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queen’, as Prince Arthur searches for the Queen of Fairyland.

The 1590 publication of the first three books of the ‘Faerie Queene’ began with “A Letter of the Author’s” – a letter written by Spenser to Sir Walter Raleigh – ‘expounding his whole intention in the course of this work’.

“Sir, knowing how doubtfully all allegories may be construed, and this book of mine, which I have entitled the Faery Queen, being a continued allegory, or dark conceit, I have thought good, as well for avoiding of jealous opinions and misconstructions, as also for your better light in reading thereof, (being so by you commanded) to discover unto you the general intention and meaning, which in the whole course thereof I have fashioned, without expressing of any particular purposes, or by accidents, therein occasioned.

The general end therefore of all the book is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline: which for that I conceived should be most plausible and pleasing, being coloured with an historical fiction, the which the most part of men delight to read, rather for variety of matter then for profit of the ensample, I chose the history of King Arthur, as most fit for the excellency of his person, being made famous by many men’s former works, and also furthest from the danger of envy, and suspicion of present time.

In which I have followed all the antique poets historical; first Homer, who in the persons of Agamemnon and Ulysses hath ensampled a good governor and a virtuous man, the one in his Iliad, the other in his Odyssey; then Virgil, whose like intention was to do in the person of Aeneas; after him Ariosto comprised them both in his Orlando; and lately Tasso dissevered them again, and formed both parts in two persons, namely that part which they in philosophy call Ethics, or virtues of a private man, coloured in his Rinaldo, the other named Politics in his Godfredo. By ensample of which excellent poets, I labour to portray in Arthur, before he was king, the image of a brave knight, perfected in the twelve private moral virtues as Aristotle hath devised; the which is the purpose of these first twelve books which if I find to be well accepted, I may be perhaps encouraged to frame the other part of political virtues in his person, after that he came to be king …”

“So in the person of Prince Arthur I set forth magnificence in particular; which virtue, for that (according to Aristotle and the rest) it is the perfection of all the rest, and contains in it them all, therefore in the whole course I mention the deeds of Arthur applicable to that virtue, which I write of in that book. But of the 12 other virtues, I make 12 other knights the patrons, for the more variety of the history …”

According to Spenser, in order to discover beauty, we must be like a Prince Arthur – striving to be a person of virtuous and gentle discipline, to become like a King Arthur, who, in real life, defended Briton from the barbarian invasion of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and also from a re-conquest by the Roman Empire, and in doing so, allowed for the subsequent spread of an esteem for an independent cultural confidence.

And I think that just as Arthur was a stepping stone that leads from the Roman Empire’s enslavement towards Briton’s independence, and just as Merlin was a stepping stone that leads from the magicians to the astronomers, then perhaps the elves and fairies could be seen as a sign that between the worlds of fact and fiction, there are stepping stones that lead us to a whole other world – a world of ideas, a world of intentions … and a world of inventions.

Our stories, like our language, didn’t evolve, but were invented (!!!) to help us explore this world of ideas. And likewise, we didn’t evolve like one of Darwin’s apes, but we were invented, by ideas.

But these stories of the world of ideas should be used to better help us to see in the real world, and not to simply create chaos, that can only be fixed by the magicians. Maybe we don’t need the magic of the magicians or the power of the empire, of the Leviathan, to impose order over the chaos. Maybe the world isn’t in chaos after all, but is merely inter-twined and inter-connected mysteries that our story-tellers help us to unravel.

But where this idea of elves and faeries, and of that mythical land ‘full with faeries’, originally came from, I’m not sure.

But we see this land once more in Shakespeare’s (i.e. Christopher Marlowe’s) ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ where we find the King and Queen of Fairyland; and we can catch a glimpse of ‘Queen Mab’ in Shakespeare / Marlowe’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’, and of the ‘Faery Mab’ in John Milton’s poem ‘L’Allegro’ and again in Percy Shelley’s poem ‘Queen Mab’.

It’s been said that John Milton had once thought of writing an epic about King Arthur, but perhaps, after writing his tracts to justify the execution of the king, and after writing his tracts in support of establishing an English commonwealth, he may have decided against writing an epic about a king, even if it was of good King Arthur. So, instead he wrote his epic ‘Paradise Lost’ about devils and angels, and Adam and Eve and a garden of Eden, that seems to have been taken from a fabulous story by Moses, and that, like Geoffrey, perhaps, was embellished by his own wonderful imagination.

And J.R.R. (Ronald) Tolkien was writing a half-finished story about King Arthur that he put aside, to begin writing a story about elves and dwarves, and a curious hobbit named Bilbo.

Perhaps as well as stories of our heroes like Arthur, stories of our elves and faeries were also left as a gift to us, a ‘promethean’ gift to man – the gift of story-telling. Since, while we sat around that gift of fire on a quiet, dark night, we discovered something to do – story-telling.

Perhaps, but that is a whole other story to explore, another time.

And so now, in conclusion, we should say that:

If Geoffrey’s ‘History’ is historically accurate, then we owe Geoffrey a world of gratitude - for having collected oral traditions and translated ancient written tracts and assembled them into a real history of King Arthur.

But if Geoffrey’s ‘History’ has simply taken certain historical events and then embellished them with his own imaginary tale, then we still owe Geoffrey a world of gratitude - for giving birth to this fabulous story of King Arthur.

I’ll leave it up to you to decide for yourself, which of these two conclusions you believe. But for me, I like to believe in both.

And perhaps, some day in our future, when people say Britain, we won’t think of the British Empire anymore, but we’ll think of King Arthur and of the independence of Briton from the empire.

And perhaps we’ll think of the elves and fairies again too. And perhaps, as Mark Twain might have thought - ‘reports of their death were grossly exaggerated’!