In Defence of King Arthur,

by a Canadian Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

While watching the decline and fall of today’s North Atlantean Empire, there seem to be many possible outcomes. One possible outcome is the complete destruction of this North Atlantean culture, and another possibility is the correction of this North Atlantean culture that will allow it to cooperate with the rest of the peoples of this planet for their common good.

Although we were taught in school that among the British people there were (and are) many good English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish people, still that word ‘British’ always had a bad taste to it, because it reminded us of the ‘British Empire’. And I’ve often wondered, what part of our cultural heritage had to be suppressed, in order to get us, North Atlanteans, to go along with this modern form of the ‘British’ empire, and also, if there was a good history of Briton, before the Anglo-Saxon barbarian invaders and the Norman feudal usurpers.

And I thought that to answer that question, perhaps we need to look at the story (or myth) of King Arthur. But before discussing whether the story of King Arthur is a myth or is not a myth, we should first look at the idea of myths in general.

Part 1 - On an Idea of Myths

Plato’s Myth of the Shadows on the Wall of the Cave

After listening to Cynthia Chung’s three wonderful classes on C.S. Lewis [part 1 - Out of the Silent Planet; part 2 - Perelandra; and especially part 3 - That Hideous Strength], her question of ‘myths’ got stuck on the back burner of my thinking cap. However, after some (early morning) fruitful discussions with some friends, a potential approach of looking at ‘myths’ came into view – that there are, perhaps, two different types of myths.

At first, it reminded me of this difference that I have between Homer and Virgil. When reading the ‘Aeneid’ of Virgil, it seems to me that it’s all about a war among the gods, and that this is what determines the fate of Aeneas. But in Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, it seems that although the gods do influence the course of events, nonetheless Odysseus must determine or change his intention that will decide his fate. And I found this same difference when thinking about myths.

Some myths excite our imagination with new and fabulous insights and emotions, while other myths excite our imagination with fantastic images and challenges, sometimes using omens and prophecies and mysteries. But not all myths are the same, as the better type of myths contain a hint of man’s moral sentiment.

This moral sentiment can be like a compass, that leads us in the direction of the reason, or the purpose, or the ‘why’ of our intentions, and it nurtures our innocent imagination with a belief, or trust, or confidence in beauty, goodness and truth.

For without this confidence in our moral compass, we are left with a different kind of intention of myths, that uses symbols and superstition, and magic and mysticism, in order to stimulate our senses with something that is simply strange or unusual or novel, that uses technique instead of art, and that aims at finding what is more powerful, not what is better. And this can leave us with an uneasy sense, or a lack of confidence, that there is any higher moral purpose.

But then, I was listening to a wonderful presentation by Nick and Julia, ‘To Dance or not to Dance, that is the question’, and Nick was asked a question about confidence in ballet dancing (but when I think about it now, his answer is actually about life), and he said that the basis of confidence is ‘esteem’.

And later, I got to thinking about this idea of esteem, and its relation to the idea of myths. If we thought that we would want to build up the cultural confidence of our population, then we would want to increase the ‘esteem’ of our population, both our own self-esteem but also our esteem for our fellow man. And then we could use a myth to portray our ‘hero’ or ‘heroine’ as someone that should be esteemed, because of his or her good character. And we would also use a tragic myth to portray those who we shouldn’t esteem, because of his or her bad character.

And so, I think that in further trying to discover the uses of myths in our works of art, we should follow the advice of C.S. Lewis. In Lewis’s ‘Last Battle’ where it is said that Narnia was only a shadow or a copy of something in the real world, Lord Digory says, “It's all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at these schools!”

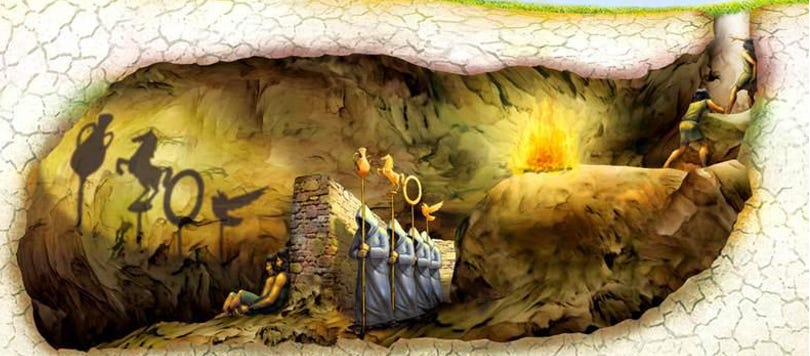

So now, we find ourselves treading on a path that was already explored by Plato – as to whether or not we should allow poets into our republic – where in book 7 of his ‘Republic’, Socrates presents us with his own myth – the fable of the shadows on the wall of the cave.

[the following quotes are from Plato’s ‘Republic’, translation by C.D.C. Reeve]

“Imagine human beings living in an underground, cave-like dwelling, with an entrance a long way up that is open to the light and as wide as the cave itself. They have been there since childhood, with their necks and legs fettered, so that they are fixed in the same place, able to see only in front of them, because their fetter prevents them from turning their heads around. Light is provided by a fire burning far above and behind them. Between the prisoners and the fire, there is an elevated road stretching. Imagine that along this road a low wall has been built – like the screen in front of people that is provided by puppeteers, and above which they show their puppets …

Also imagine, then, that there are people alongside the wall carrying multifarious artifacts that project above it – statues of people and other animals, made of stone, wood, and every material …

All in all, then, what the prisoners would take for true reality is nothing other than shadows of those artifacts …

Consider, then, what being released from their bonds and cured of their foolishness would naturally be like …

What do you think he would say if we told him that what he had seen before was silly nonsense …”

Socrates then imagines a man who is freed, but because of the pain – from moving from his fetters and from looking at the light, he was puzzled and fled back to the shadows that he was able to see before; and he had to be dragged up into the light until he slowly got accustomed to seeing things in the light of the sun, and not as shadows.

“And if there had been honors, praises, or prizes among them for the one who was sharpest at identifying the shadows as they passed by; and was best able to remember which usually came earlier, which later, and which simultaneously; and who was best able to prophesize the future, do you think that our man would desire these rewards or envy those among the prisoners who were honored and held power? Or do you think he would feel with Homer that he would prefer to go through any sufferings, rather than share their beliefs and live as they do?”

Socrates then imagines that this man went back down into the cave, coming away from the light of the sun and going into the darkness of the cave, and he sat in his same seat as before.

“Now, if he had to compete once again with the perpetual prisoners in recognizing the shadows, while his sight was still dim and before his eyes had recovered, and if the time required for readjustment was not short, wouldn’t he provoke ridicule? Wouldn’t it be said of him that he had returned from his upward journey with his eyes ruined, and that it is not worthwhile even to try to travel upward? And as for anyone who tried to free the prisoners and lead them upward, if they could somehow get their hands on him, wouldn’t they kill him?”

Now, it seems that instead of having two types of myths, we have two types of myth-makers – one, like the highly-praised ‘perpetual prisoner’ who predicts the future by interpreting the shadows on the wall, and the other, like the ridiculed ‘escaped prisoner’ who returned to the cave trying to tell others about the world in the sunshine that he had seen.

And while I don’t think that we should ban all myths, I also don’t think that we should ban all myth-makers, just as we should not ban all poets in our republic. Because it is up to us, to encourage those poets and those myth-makers whose intention was to act as a stepping stone to making us better persons, and to discourage those poets and myth-makers whose intention wasn’t to make us better persons, but were simply fantasies about ego or revenge or arrogance or narcissism.

And with all that in mind, perhaps now we can look at which type of poet or myth-maker is telling us the story of King Arthur.

[ next week - part 2 - the Malign and False History of Edward Gibbon]