God’s Spies – Spenser and Marlowe

“Come, let's away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i' the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I'll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we'll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we'll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who's in, who's out;

And take upon's the mystery of things,

As if we were God's spies …” [from King Lear, Act V, scene iii]

This is a story about ‘William Shakespeare’. While some scholars assert that a different writer was the actual author of Shakespeare’s plays, like Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford, there’s not much evidence for these two. However, one other theory that gathers much evidence is that Christopher Marlowe was the actual playwright. Much has been written about Marlowe and much has been written about Shakespeare, and while some of it is very interesting, some of it is merely hearsay or gossip or imagined. Trying to unravel what is myth and what is possible, and what we should believe about their lives, is often a painstaking and thought-provoking exercise, but one that however might bring us a little closer to seeing the real ‘William Shakespeare’ and the real Christopher Marlowe, and to glimpse a story of what might have been.

Act 5 - Republic or Empire

In 1599, Giordano Bruno was found guilty of heresy. Earlier, in May 1592, because of a letter of accusations by Giovanni Mocenigo, Bruno was arrested and interrogated by the Venetian Inquisition. But while three witnesses were brought against him (two booksellers and a nobleman), nothing could be found to support these charges.

Venice, in responce to a request by the Roman Inquisition, sent Bruno to Rome. For the next six years the Inquisition prepared a list of Bruno’s writings and searched throughout Europe for any copies that could be found. But the Inquisition was unsuccessful in building its case against him, until in 1599, the Pope made Jesuit theologian, Roberto Bellarmino, a cardinal and an Inquisitor placed on the Board of Inquisition, that then found Bruno guilty. In February 1600, Bruno was burned at the stake, so that his name might be infamously remembered.

Although Marlowe’s next plays are again set in Italy, I suspect that Marlowe however remained in London, perhaps fearing the Venetian Inquisition.

We know that he might have been in London because sometime around the year 1602, a ‘William Shakespeare’ rented a room in Cripplegate ward at the home of French immigrants, Christopher and Marie Mountjoy.

[Note: In ‘Henry V’, the French herald is named Mountjoy.]

This can be found in the legal documents from a court case that was heard in 1612 – ‘Belott v. Mountjoy’, a family dispute of Stephen Belott, the son-in-law and former apprentice of Christopher Mountjoy, French immigrants and makers of ladies decorative head attire – ‘tire-makers’. Belott claimed that Mountjoy promised him a dowry of £60 when he married Mountjoy’s daughter, Mary, in 1604, but it was never paid.

One of the witnesses called was ‘William Shakespeare’, a lodger at Mountjoy’s residence at the time, who said that he knew both parties – ‘as he now remebrethe for the space of tenne years or thereaboutes’. A ‘William Shakespeare’ had moved from the Liberty of the Clink in Southwark, near the Globe theatre and the Rose theatre, to live at the Mountjoy’s, around 1602 or thereabouts.

[The Deposition of ‘William Shakespeare’ of May 11th 1612 is found in ‘The Lodger Shakespeare, His Life on Silver Street’, by Charles Nicholl.]

But shortly before that time, in 1597, a large house was purchased in the name of a ‘William Shakespeare’ – the second-largest house in all of Stratford-upon-Avon. When his father, John, died in 1601, William would inherit his properties. So, why would a fairly prosperous merchant living in Stratford-upon-Avon, wish to rent a ‘room’ at the home of French immigrants. Especially if he didn’t speak French – which Marlowe did.

The Mountjoy house in Cripplegate would’ve been a short walk to St. Paul’s churchyard and booksellers’ stalls – the main market for the book trade.

St. Paul’s churchyard is mentioned in the 1600 publication of Marlowe’s English translation of Lucan’s First Book of Pharsalia (on the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey) – which would have been Marlowe’s research to be used for his play Julius Caesar, published by Thomas Thorpe.

In it, Thorpe writes an introduction to his friend Edward Blount, who had earlier published Marlowe’s poem ‘Hero and Leander’:

“Blunt, I propose to be blunt with you, and, out of my dulness, to encounter you with a Dedication in memory of that pure elemental wit, Chr. Marlowe, whose ghost or genius is to be seen walk the Churchyard, in, at the least, three or four sheets. Methinks you should presently look wild now, and grow humorously frantic upon the taste of it …” Was Thorpe hinting that he had seen (or met) Marlowe at St. Paul’s?

Why would ‘William Shakespeare’ want to take up residence with a French immigrant family in Cripplegate, unless he spoke French (like Marlowe) and used to live in France (like Marlowe) and where he could receive news (and intelligence) from France, and where he could also be near the St. Paul’s booksellers, where he could also receive news (and intelligence) of other playwrights? Perhaps this must have been Marlowe.

The deaths of Bruno, and of Essex, may have been in Marlowe’s thoughts when he wrote the play ‘Othello’, set in Venice, again, and with the manipulative Iago, that should remind us of the Venetian disease that was beginning to infect England, as seen in Paolo Sarpi, and in Francis Bacon and Robert Cecil.

[Note: It is a proven ‘fact’, that Bacon was in correspondence with the Venetian Sarpi, and that Bacon’s ‘so-called’ method was just a rehash of Sarpi’s and was promoted as if it was something original or meaningful.]

Queen Elizabeth had died in March 1603, and with that death also came the end of Elizabethan England. Due to his secret correspondence with Cecil, James Stuart made a smooth transition from King of Scotland to become King of Great Britain, and he soon made peace with Spain, knighted Bacon, and made Cecil a Baron.

Set in Rome, are three plays - ‘Coriolanus’, ‘Julius Caesar’ and ‘Antony and Cleopatra’, where Marlowe studies the ending of the Roman Republic and the beginnings of the Roman Empire, and the potential future of England.

In ‘Julius Caesar’, we see this problem in the discussion between Cassius and Casca the cynic:

“CASSIUS – Did Cicero say any thing?

CASCA – Ay, he spoke Greek.

CASSIUS – To what effect?

CASCA – Nay, an I tell you that, Ill ne'er look you i' the face again: but those that understood him smiled at

one another and shook their heads; but, for mine own part, it was Greek to me.”

The one person who could have saved the republic, Cicero, was not listened to or was not to be understood – it was Greek to me!!! We are reminded of what Thomas More, in the beginning of his ‘Utopia’, wrote :

“This Raphael … is not ignorant of the Latin tongue. But is eminently learned in the Greek, having applied himself more particularly to that than to the former, because he had given himself much to philosophy, in which he knew that the Romans have left us nothing that is valuable, except what is to be found in Seneca and Cicero.”

‘The Tempest’ would be Marlowe’s last play. In the epilogue, Prospero (i.e. Marlowe) now that he has set free Ariel (i.e. his Muse) asks to be released from his exile. Since he has ‘pardoned the deceiver’ (i.e. relieved ‘Shakespeare’ of his responsibility) he wishes that all can be forgiven – ‘let your indulgence set me free’.

Now my charms are all o'erthrown,

And what strength I have's mine own,

Which is most faint: now, 'tis true,

I must be here confined by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got

And pardon'd the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell;

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands:

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon'd be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

‘Shakespeares Sonnets’ would be published in 1609 in a small one-time printing for friends. No new plays by ‘William Shakespeare’ would be published after this, but it is believed that the ‘bard’ spent the rest of his remaining years, collaborating with other young aspiring playwrights to help them learn the poetic art.

How Christopher Marlowe actually died or when he actually died or where he was buried, we may never know. William Shakespeare died in Stratford-upon-Avon in April 1616 and was quietly buried in Holy Trinity Church, but upon the news of his death, no eulogies or memorials were written by other poets or playwrights, no gatherings were held in London or elsewhere, no poems or pens were tossed into his grave, as it was done for other poets. Nothing was said or done about this William Shakespeare’s death. If he was so loved, why was nothing done upon his death, and why would six years have to pass before someone began the process to publish his works?

I suspect that Christopher Marlowe may have died around 1621, and that was why in 1622 the work began on collecting and type-setting his plays, and in 1623 the First Folio of William Shakespeare’s collected plays would be published.

In 1632, the Second Folio was published, and which would contain a sonnet written by an anonymous poet –

‘An Epitaph on the Admirable Dramatick Poet, W. Shakespeare’:

“What needs my Shakespeare, for his honoured bones,

The labour of an age in piled stones?

Or that his hallowed relics should be hid

Under a star-ypointing pyramid?

Dear son of Memory, great heir of Fame,

What need'st thou such weak witness of thy name?

Thou, in our wonder and astonishment

Hast built thyself a livelong monument.

For whilst, to the shame of slow-endeavouring art,

Thy easy numbers flow, and that each heart

Hath, from the leaves of thy unvalued book,

Those Delphic lines with deep impression took;

Then thou, our fancy of itself bereaving,

Dost make us marble, with too much conceiving;

And, so sepulchred, in such pomp dost lie,

That kings for such a tomb would wish to die.”

The writer of that anonymous sonnet to the immortality of ‘William Shakespeare’, turns out to have been a 21-year-old young man named John Milton, who would later find employment as a private tutor (a schoolteacher) until he was called upon to become the Foreign Secretary of the English Commonwealth, under Oliver Cromwell.

Hmmm … it’s funny how this immortality thing seems to find a way to repeat itself.

Also included in that First Folio (1623) was a poem written by Leonard Digges, that contained the lines:

“Shakespeare, at length thy pious fellowes give

The world thy Workes: thy Workes, by which, out-live

Thy Tombe, thy name must when that stone is rent,

And Time dissolves thy Stratford Moniment …”

The word ‘moniment’ differs from the word ‘monument’, and ‘moniment’ refers to a reminder or inscription – i.e. to the plaque that was placed on the wall of the Stratford church:

“Stay Passenger, why goest thou by so fast?

Read if thou canst, whom envious Death hath plast,

With in this monument Shakspeare: with whome,

Quick nature dide: whose name doth deck Ys (this) Tombe,

Far more then cost: sieh all, Yt (that) he hath writ,

Leaves living art, but page, to serve his witt.”

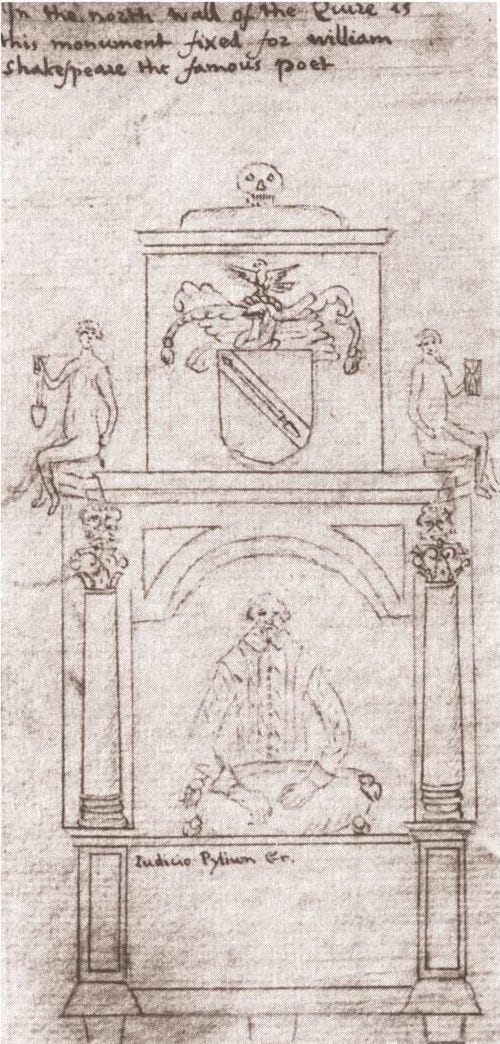

The first actual evidence of a ‘monument’ was published in ‘Antiquities of Warwickshire Illustrated’ in 1656, by William Dugdale, that contained an engraving done by Wenceslaus Hollar, and that was based on an earlier sketch done by Dugdale in July 1634.

Dugdale sketch, 1634

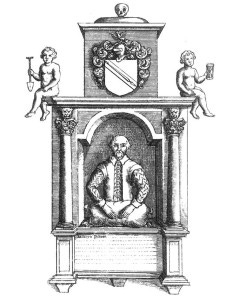

Hollar engraving, 1656

Another engraving of the ‘monument’ also appeared in Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of ‘The Works of Mr. William Shakespear’.

Rowe engraving, 1709

As can be seen in the sketch of the Stratford wall monument done by Dugdale, in the engraving done by Hollar, and in the Rowe engraving, ‘Shakespeare’ is holding a ‘wool-pack’ suggesting that he was a merchant.

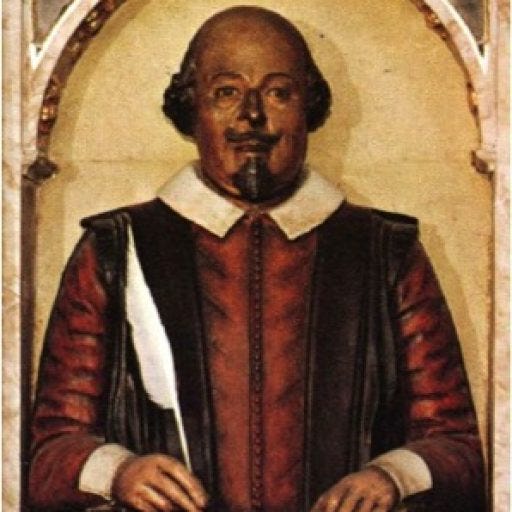

The monument underwent significant restoration in 1649-1650 (after the Civil War), so that by 1725, (over a hundred years after his death) an engraving by George Vertue, in Alexander Pope’s edition of Shakespeare’s plays, shows Shakespeare holding a pen and paper.

Vertue engraving, 1723

After numerous restorations, repairs and re-paintings, the monument looks like this today.

William Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

This may have been how William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon looked like, although it looks nothing like the statue of William Shakespeare that is in London at Westminster Abbey (100 miles away).

William Shakespeare statue at Westminster Abbey

There had been much talk of burying ‘Shakespeare’ (i.e. Marlowe) at Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, near Edmund Spenser.

In 1741, a statue of Shakespeare was erected in Poet’s Corner by Alexander Pope, Richard Boyle, Richard Meade and Tom Martin. This is not the same face as that of the wealthy wool merchant that is buried in Stratford, but it resembles the portrait of Christopher Marlowe (done in 1585) that was rediscovered in 1953.

Shakespeare statue, 1741

Marlowe portrait, 1585

So perhaps, the spirit of ‘William Shakespeare’ (i.e. Christopher Marlowe) is resting where he truly belongs after all - in Poet’s Corner!

And perhaps, it could be said that Marlowe had escaped death twice - once at the ‘reckoning’ and again, to stand forever at Westminster Abbey …

… as if he were God's spy ...

**********

for Further Inspiration, please watch this video presentation:

Marlowe as Shakespeare: The Drama of Political Intelligence and the Education of a Citizenry

– a lecture by Martin Sieff, November 8, 2020 at RisingTideFoundation.net

for Further Reading:

The Death of Christopher Marlowe, by J. Leslie Hotson

The Reckoning, the Murder of Christopher Marlowe, by Charles Nicholl

The Book Known as Q, a Consideration of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, by Robert Giroux

The Story That the Sonnets Tell, by A. D. Wraight

Marlowe Up Close, an Unconventional Biography, by Roberta Ballantine